At the dazzling Beijing Olympics opening ceremony, China's invention of printing 1,968 years ago was celebrated by thousands of performers hoisting tiles bearing Chinese characters above their heads. These squares symbolized the imprinted clay blocks used during the infancy of Chinese printing. It was also a reminder of how far Chinese printing has come into the computer age.

When peasant Bi Sheng devised movable block type in 1040, he was merely writing the first page of the story of the Chinese printed word - a legacy complicated by the fact that Chinese is written in hanzi, or characters developed from pictographs.

Performers present a show featuring movable types at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics in Bird's Nest August 8 2008. [Xinhua] |

The latest monumental achievement came with the computerization of Chinese in the 1980s.

Alphabetic scripts enjoyed an easier transition to the digital age because they contained no more than a few dozen letters. However, Chinese-language printing requires several thousand unique characters, so whether dealing with clay, wooden or metal blocks, or digital renderings, storing and sorting so many characters was always a challenge.

Those who undertook the task of taking Chinese printing into the digital age faced the question of developing a keyboard capable of typing thousands of characters. Then there was the challenge of storing the thousands of characters as images without requiring a huge amount of memory.

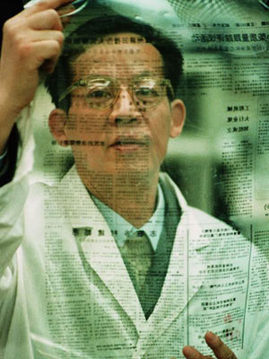

Wang Xuan, whose findings computerized Chinese characters. |

The man who came up with the solution was Wang Xuan (1937-2006), a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering, and the former chair of software leader Founder Group.

Hailed as a modern Bi Sheng, Wang developed a large-scale integrated circuit capable of efficiently storing compressed information in hanzi and a five-stroke input method in 1975. He went on to devise a laser-printing system for characters. In 1980, a 26-page text about kung fu that rolled off his press became China's first laser-printed book.

Xia Tianjun, the former director of Economic Daily's printing house, recalls working with Wang to fix the glitches in the system after the paper first tried it in 1987.

"He promised he'd get rid of all the bugs within 15 days or bring back the old typesetting system," Xia said.

Wang and his wife Chen Huanqiu, who tinkered with the characters and punctuation marks, worked tirelessly.

"By the deadline, everything was running smoothly," Xia recalled.

Wang Ziliang, 62, who was deputy director of People Daily's publishing house for 20 years, also saw firsthand the transition from lead-cast character blocks to digital printing.

Wang said that the character blocks were stored in row upon row of boxes sorted according to the number of character strokes.

The vice-president of the China Academy of Printing Technology, Chi Tingling, said most printing houses of the era had about 60 blocks of nearly 6,000 characters in every typeface. They were stored in small cartons stacked inside booths spread among several rooms, covering more than 66,000 sq m.

"It was a huge job remembering where all of the characters were stored," Wang said.

Once his department received the last copy at 2 am, the printing house team would begin frantically hunting for and inserting the blocks in a 13-kg metal frame.

"A skillful worker could place 100 characters per minute," Wang says. If articles were too short, lead strips would be placed to expand spaces between lines.

The characters would become increasingly distorted throughout the night from being mashed in printing page after page, so every day they would melt the blocks down to cast new ones. Those making the lead type worked with toxic chemicals, such as potassium cyanide.

"A lot of people were poisoned by fumes or by absorbing toxins through their skin," Wang says. Typesetters received a bonus of 1 jiao a day for facing such risks.

It would take two to three hours to finish an edition, and when it was done, "we were covered with ink. It coated our hands, our clothes, our faces, so at the end of every shift, we looked like Bao Gong", Wang says, referring to a Peking opera character known for his blackened face.

As Chi said: "Because of the complexity of the process, China's printing industry lagged behind the rest of the world for some time."

But that began changing about three years after Wang Ziliang moved to Economic Daily's printing house in 1984.

While laser printing generally made production faster and easier, it also brought a new host of challenges, he said.

"The new generation of pressmen had to keep up constantly with the latest printing and computer technologies, and they had to learn English, because many of the computers were imported," Wang said.

At that time, there were only 20 laser-printing systems in the country - 18 in Beijing and two in Sha'anxi province.

As the technology spread, the world of publications in the country expanded, leading to a nationwide information revolution. The language's computerization made text digitally transferable and retrievable, so that the impact became global.

In 1990, Economic Daily sent an electronic version of its paper from Beijing to Guangzhou via satellite - a huge jump from the days when Hebei province's typesetters would have to replicate completed copies of People's Daily brought in from Beijing, Wang said.

Xia agrees. "The technology was like a huge motor that sped up newspaper production," he said.

According to Adam Solove, the founder of Digitalsinologist.com, the computerization of Chinese has also revolutionized Sinology - the academic study of China - by making information easily retrievable and searchable.

"These technologies make it possible for us later scholars who haven't been brought up with a classical Chinese education to read and understand classical Chinese texts," Solove said.

"Because we are less dependent on existing commentaries and can easily search through large pools of information, we can study topics traditional scholarship might have missed," he added.

Renowned German Sinologist Wolfgang Kubin, who has published the magazine Minima Sinica for 20 years, says the digitalization of characters has changed the way he runs his publication.

"The revision of any volume took me months. Now. (I can) translate more, and quicker and even better."