Memory crash

(China Daily)

Updated: 2010-06-30 09:52

|

Large Medium Small |

China needs to act fast to cope with the escalating number of dementia patients

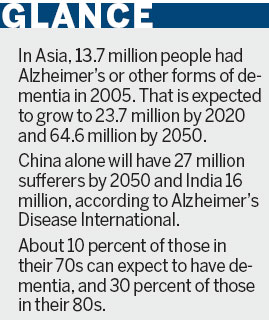

Asia's fast-aging population will make up more than half of the world's dementia patients in 40 years, with China shouldering the biggest burden.

With very few skilled nursing homes, daycare facilities or plans to build many more, health experts say the region is ill-prepared to cope with the sharp increase in patients needing such specialized and intensive care.

"Asia will bear the burden because of the aging population in China ... figures in China will be tremendous," says Dr David Dai, coordinator of the Hong Kong Alzheimer's Disease Association.

"We are not prepared. The whole of southeast Asia is not prepared," gerontologist Dai says.

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, robs people of their memory and thought processes and, eventually, bodily functions.

"Everyone will experience this, every family. It is now common to live to your 80s," says Peter Yuen, director of the Public Policy Research Institute at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

In the United States, the annual amount spent by the government, private insurance and individuals to care for people with AD, is projected to jump more than six-fold to $1.08 trillion by 2050, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

The costs are just as substantial elsewhere.

Yuen, whose mother has Alzheimer's, told a recent AD symposium in Hong Kong that four years of daycare and two years of residential care in a general nursing home in Hong Kong would cost HK$540,000 ($69,000) per patient.

But even that is an underestimate for 82-year-old Aw Bek-sum, whose children have had to fork out HK$15,000 ($1,920) each month to take care of her since she was diagnosed with Alzheimer's four years ago. The sum covers daycare, visits to the doctor, a domestic helper and household expenses.

"It's devastating for families with AD patients. There is just not enough support," Yuen says.

He proposes long-term financing or some form of pooled insurance for patients who are chronically ill so that services will be made available once the ability to pay is assured.

Dedicated facilities for AD patients are scarce in Asia. China has up to 8 million dementia patients, but very few hospitals in the country have independent dementia units.

Hong Kong, for instance, has 110,000 patients but only 299 places in four daycare centers, and not a single residential care facility. Many end-stage sufferers are put into general nursing homes where staff are not trained to care for them.

"In nursing homes, their conditions get worse because they are normally tied down and they don't have any social interaction, then they die quickly," Dai says.

In Malaysia, an estimated 50,000 people suffer from dementia.

"Very few private nursing homes are dedicated to the care of the AD sufferer, although some homes will accept a few AD sufferers if they are not behaviorally challenged," says Philip Poi, head of Geriatric Medicine at University Malaya.

"Malaysia is starting to appreciate there is a problem, but currently, care giving is provided mainly by the informal carers such as the spouse or child."

By 2030, one in every four Chinese will be over 60. "Because of China's aging population, the government sees stronger demand for care and medical facilities for the old. It's possible that in the next few years, China will establish more facilities and organizations for old people and dementia patients," says Zhang Shouzi, deputy manager of the Beijing Geriatric Hospital's dementia unit.