Dou Wan, an enigma wrapped in a shroud

Zhao Xu

For one who was given such an ostentatious sendoff when she died, the most surprising thing about Dou Wan is just how much about her is shrouded in mystery.

The burial garb of a regal woman who left barely a trace has crowds gasping

For one who was given such an ostentatious sendoff when she died, the most surprising thing about Dou Wan is just how much about her is shrouded in mystery. In fact we know neither when exactly she was born nor when she died, and next to nothing about what she did between those two unknown dates, including the children she probably had. Yet this woman, who married a vassal king during the Han Dynasty (202 BC-AD 220), was given a burial grand enough to ensure she could never be forgotten.

The best-known item that this funereal pomp produced is what is known today as the jin lv yu yi, or jade outfit sewn up with golden thread. Made up of more than 2,000 rectangle jade pieces and gold threads weighing 700 grams, this unbelievable garment of death encased Dou's largely rotted body when her tomb was excavated, soon after the accidental discovery of that of her husband, in 1968. As the archaeologists carefully dug, the jade garment was revealed and beckoned people with a faint but distinct shimmer.

It is now on display at the National Museum of China in Beijing in a blockbuster exhibition focusing on a period of history widely regarded today as having laid the foundations for Chinese civilization. At least half of the 300 exhibits on display deserve to be called national treasures, but standing head and shoulders above them all is the shroud, as it is called in the exhibition catalog, which has visitors elbowing one another out of the way for a better view that leaves many gasping.

The fact that the owner of the shroud was a female is not directly evident. True to its name, it was so bulky that more than 2,000 years ago when the fragile body of Dou was laid to rest in it, it must have amply wrapped her up.

However, all this splendor fits perfectly with the enigma that is Dou, concealing as much as it reveals. The woman had wealth and status, but what else? "For answers, we have to look closely at other items, items that came to light with the shroud," says Wu Zhen, of the Hebei Provincial Museum where the garment is normally held.

The burial ground of Dou Wan lies a mere 100 meters north of that of her husband, Liu Sheng, a vassal king whose father, Liu Qi, was the fourth emperor of the Han Dynasty. "Both burial grounds are on a mountain slope in Mancheng in central Hebei province. In 1968 the construction of an air-raid shelter led to excavation that in turn led to the discovery of an underground crypt," Wu says.

"The crypt turned out to be one of the two side chambers of Liu's underground tomb, and was used to house chariots and horses. The other was for cooking utensils and food and wine containers."

After it was established that the tomb belonged to Liu Sheng, a Han Dynasty vassal king, based on the discovery of inscribed objects, the archaeologists looked for anything that might point them to the existence of another burial ground, one belonging to his spouse, in the area.

"Then they noticed a stone-strewn ground not far away," Wu says. "The gravel seemed to have been the product of human effort. They dug into the earth, and we have what we know now: an aristocratic lady whose afterlife was steeped in luxury, and her life in mystery."

Based on what could be found out about Liu Sheng, her husband, archaeologists and historians have discovered some tantalizing hints about some aspects of that mystery.

Ban Gu, a renowned historian who was born in AD 32, 145 years after the death of the vassal king in 113 BC, painted a rather wanton portrayal of the man in his definitive history Han Shu (The History of Han). In it Liu is quoted declaring that the main responsibility of a vassal king is to have fun, a declaration that seems to have drawn a furious rebuke from a fellow king. "Your duty is to improve the lives of those within your own kingdom and assist the emperor," Liu was told.

Wu says that seeing Liu as someone who was only out for a good time understates his "quick wit and literary flair."

One example is a short piece of prose, the only written piece Liu left, that he penned about a fine piece of grained wood. It is filled with a majestic elegance befitting a king. Another instance is his pleading in front of the emperor, his younger brother and the ultimate ruler of all land, including his.

That brother, nine years younger than Liu Sheng, was Emperor Wudi, unarguably the greatest emperor of the Han Dynasty and possibly in Chinese history. Determined to consolidate his rule, the emperor kept a suspicious eye on all of his vassal kings, always prepared to strike at the first sign of disobedience. The kings, for their part, lived in anxiety and even fear.

Liu Sheng laid out his own case at a banquet hosted by the emperor, with what today is regarded as an oratorical masterpiece. The improvised speech is both powerful and persuasive, with what is said to have been his signature eloquence, but with a hefty dose of emotion as well.

However, the emperor was clearly not moved enough to pull back from his course to reduce and undermine vassal power. The empire continued to shrink in the years after Liu Sheng's death. But for the 42 years he lived he enjoyed relative safety on his own turf, nearly 1,000 kilometers from Chang'an, capital of the Western Han Dynasty, in what is now Shaanxi province.

"In retrospect, Liu Sheng's self-proclaimed love of debauchery may have been a ruse designed to fend off potential danger from a wary emperor and his mighty troops," Wu says. "Growing up witnessing the death of his rebellious uncles and grand-uncles at the hands of his own father, Emperor Jingdi, Liu Sheng was wise enough to stay out of harm's way."

Or perhaps over the years the king had convinced himself that to live an intoxicated - sometimes literally so - life was indeed the best for him. Whatever the case, Liu Sheng seemed to have adhered to that hedonic image of his diligently and consistently, nurturing his literary genius over cups of wine.

The king fathered more than 120 sons - and an unrecorded but presumably large number of daughters, a feat that might only be expected of a lecherous Greek god. Were any of these children mothered by Dou Wan? We do not know.

"Many historians believe Dou Wan was a distant relative, possibly a grandniece, of Dou Yifang, the empress of Emperor Wendi and mother of Emperor Jingdi, a strong believer of Taoism who stayed in the center of politics for nearly two decades," Wu says.

"That connection provided Dou Wan with a much needed layer of protection amid all the volatility surrounding a spouse of a king."

Items unearthed from her tomb - some clearly having been used before their burial - offer a glimpse into their owner's life. One is a gilt bronze lamp in the shape of a kneeling maid. Holding the tray, in which blocks of animal fat were placed, with the left hand, the maid lifts up her broad-sleeved right arm to the top of the lamp. (Candles were not invented until much later.)

In an ingenious design touch, the sleeve column serves as a tunnel through which the smoke produced by the burning of congealed oil is channeled into the maid's body. In fact, a vestige of smoke was discovered on the inner wall of the hollow space.

Moreover, both the tray and the shade of the lamp could be turned around, making possible the adjustment of the light's direction and intensity.

"Inscriptions suggest the lamp changed hands several times, before it became owned by Dou Wan and followed her underground," Wu says. "We have reasons to believe that the lamp was treasured by its owner, who might have toyed with it during those long hours of her husband's absence."

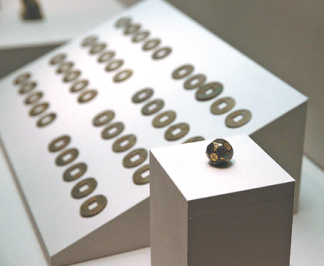

The lamp is known today as the "Changxin Lamp", changxin being inscribed on it and referring to the name of the palace where Dou Yifang, the powerful empress dowager, once resided. At the national museum it is displayed alongside a collection of copper coins and a multifaceted copper dice embedded with gold and silver and set with agate and turquoise.

The copper coins and the dice are items of entertainment, used for game play during extensive drinking sessions, Wu says.

"Dou Wan herself may have been a wine lover, given the discovery of wine containers and cups in her tomb. But it's also possible she took part in such activities or even promoted them in an effort to be close to the world of her husband.

"Given the scant information available, whether Dou Wan died before or after her husband is likely to remain unknown. Some historians leaned toward the 'before' view, arguing that the funerary objects unearthed in Dou's tomb were less magnificent than those of Liu. But proponents of the 'after' case point to the woman's burial ground being larger.

When the archaeologists looked inside Dou Wan's coffin in 1968 they found 47 knives. In an era when people recorded things on bamboo slips, the knife was the pen.

"The fact that Dou was wearing it upon her burial says a lot; she is likely to have been a woman of letters. And this hobby could have been the mental and emotional bridge that linked her with the man of her life."