Calligraphy, the gem of Chinese culture

Guo Jiulin

Calligraphy is something every special for Chinese. It is not only an important part of traditional Chinese culture but also a way of life for people of all stripes.

Calligraphy is something every special for Chinese. It is not only an important part of traditional Chinese culture but also a way of life for people of all stripes.

Like oil painting and sculpture in the West, calligraphy is as much an artistic form as a spiritual anchor for many Chinese throughout history. Rarely does any other culture in human history fascinate with calligraphy in such a profound way.

From the invention of hieroglyphics to the evolution of various calligraphic scripts, calligraphy has played a critical role in Chinese culture and history for thousands of years.

Calligraphy was well-respected, or even worshiped in history. It was a foundation for scarcely available education opportunities, a steppingstone to become the elite class and a prerequisite for admiration among peers. In essence, calligraphy is also the cultural identity and the manifestation of collective aesthetic philosophy.

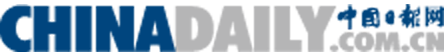

During Jin Dynasty (AD 265-420), calligraphy became an expression of superiority among noble families. The rivalries were so intense that young children were ordered to receive extensive training in calligraphy.

Wang Xizhi was among those raised in noble families. Along with his son, Wang Xianzhi, the Wangs were considered the greatest calligraphers in Chinese history whose achievements were insurmountable for late generations. Therefore, Jin Dynasty is the pinnacle of calligraphic works in Chinese history.

However, calligraphy inevitably intersected with politics in Chinese history.

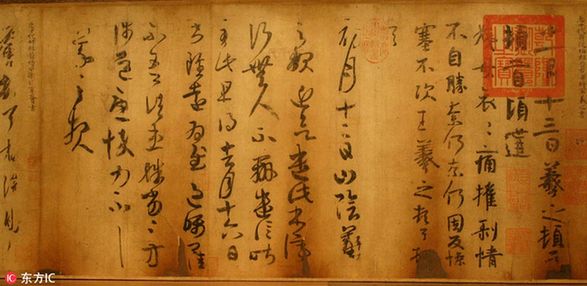

In Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), the Emperor Taizong not only revered Wang Xizhi's calligraphy, but himself was also good at it. He considered Wang Xizhi as the greatest calligrapher in history. His obsession with Wang Xizhi made him promote his subordinates based on their talents to mimic Wang's works.

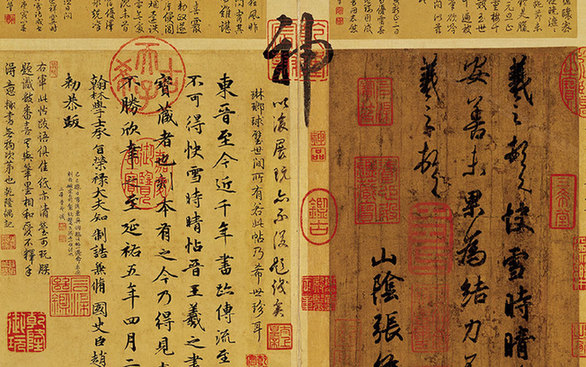

Above all, the emperor regarded the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection by Wang Xizhi as the best running script. Prized as his priceless treasure, the emperor kept Wang's works only for his most trusted subordinates and, after his death, he was buried along with Wang's works.

It was understood that calligraphy became one piece of matrices for the emperor to seek loyalty, unity and capability among his subordinates. Not surprisingly, Tang Dynasty was another Golden Age of Chinese calligraphy. A generation of great calligraphers, such as Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, Yan Zhenqing, Sun Guoting, Liu Gongquan and many others, emerged whose calligraphic works also became masterpieces for later generations to emulate.

Calligraphy in ancient China was critically important for Chinese literati.

Since the practice of the imperial examination, calligraphic skill may change the fate of those examinees. It was generalized that, since so few were able to receive formal education, their intercultural ability and their qualification to serve the emperors correlated with calligraphy.

Moreover, the examiners might not have enough time to go through all the essays, and they tended to rank candidates based on calligraphy rather than contents. Therefore, calligraphy somewhat became a strong indicator for talent and promotion.

Even in daily lives, people with calligraphic skills were highly respected and in high demand for letters, contracts, Buddhist scriptures, as well as decorations for weddings and funerals.

Nowadays, zhongtang, which consists of three pieces of calligraphic works and a water-color painting, is the most elegant feature of the living room and is still popular in rural areas of northwestern China.

It is a meticulous plan to set up the zhongtang in order to impress the guests. The choice of calligraphy and, most importantly, its meaning reflects the social status in the neighborhood and is considered as one of the most important assets for fortune and prosperity for generations.

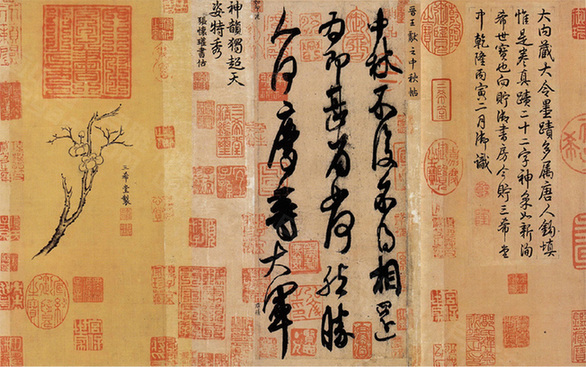

Although urbanization offers limited space required for traditional zhongtang, it is still a common practice for many to assemble calligraphic works in the living rooms. In modern China, calligraphy in such formats as mottos has emerged as an expression of aesthetic philosophy and personality.

Calligraphy used to be a privilege among the well-educated elites. Nowadays, significant reduction in poverty and illiteracy encourage more and more people to practice calligraphy. As much as recreation, physical fitness and artistic appreciation, calligraphy is becoming a part of life among many Chinese people. With numerous calligraphy training courses and interest groups among local schools and communities, plus various calligraphic competitions, exhibitions and auctions, today is another Golden Age of Chinese calligraphy.

About the author:

Guo Jiulin is professor of Dalian Nationalities University (DNU) and the institute director of Comparative Study of Chinese and Western Cultures at DNU