Sing me a story

Updated: 2019-11-15 07:48

By Neil Li(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

Neil Li finds out about the forgotten art of naamyam singing and recent attempts to enhance its appeal among newer audiences.

Even before people learned to write, stories would be passed down verbally from one generation to another. These tales were sometimes delivered through spoken words and at other times through song, with the latter resulting in the emergence of some truly unique art forms, such as that of naamyam..

Naamyam is a form of narrative singing that originated in Guangdong and was commonly heard in restaurants, tea houses and brothels in the early to mid-20th century. Performances were typically accompanied by string and percussion instruments like a guzheng, yehu or wooden clapper.

|

Top: Ethnomu-sicologist Bell Yung with naamyam exponent Dou Wun in the 1970s. Above: scene from Zuni Icosahedron production, Blind Musician Dou Wun. |

According to Chan Hing-yan, composer and professor of music at the University of Hong Kong, naamyam was most popular in Hong Kong in the 1940s and 50s. Before the advent of Cantopop, Western pop and television, it was a major form of entertainment for people in southern China and regularly played on the radio.

"Back then, naamyam was a part of life. When you (went out onto) the street, you would see beggars singing naamyam. Naamyam would be part of the entertainment during Chinese New Year celebrations as well as at birthday banquets. Fortune tellers would even sing people their fortunes in naamyam," says Chan.

Naamyam was also used to transmit information. For example, Dou Wun, a famous practitioner of the art form from the 1950s to mid-1970s, would listen to the news on the radio and then sing about it the next day at tea houses. Other common themes covered by this musical genre include those of unfulfilled love or the death of a lover.

Popular interest in naamyam began to wane in the 1970s as other forms of music became popular and television overtook the radio. For a while, naamyam would figure in Cantonese movies but eventually it was too hard for the traditional art form to keep up with the times.

Uniquely Cantonese

A typical naamyam song consists of sentences with just seven characters, which are usually divided into four-plus-three arrangements, each line ending following a particular cadential formula. A naamyam singer would learn this formula and then fill in the text of his story accordingly.

"The melody (of the song) is basically there already but different singers have their own way of embellishing it," Chan says. Variations on the standard melody could be brought about by changing the tempo, he adds. "The faster the tempo, the fewer the embellishments and vice versa. It's similar to jazz and its chord progression."

To the untrained ear, naamyam might sound very similar to Cantonese opera as the latter incorporates a number of different musical elements, including naamyam. Compared to Cantonese opera, however, naamyam is a minimalistic and pared down musical form. There are no acting, choreography and elaborate costumes - just a solo performance by a singer, accompanied by one or two instruments. The melodic formulas are simpler than those found in Cantonese opera.

Naamyam is always sung in Cantonese as its music is intrinsically linked to the language. "Any kind of narrative singing is very much related to its language or dialect," says Chan. "I always tell my students that there is no national style in Chinese music, but there are a lot of regional styles. Naamyam is just like how certain dishes can only be a Cantonese dish."

Finding new audiences

Despite the decline of naamyam in the 1970s, a small group of enthusiasts in Hong Kong are making efforts to preserve this art form. Hong Kong government's Leisure and Cultural Services Department and other cultural organizations host events featuring naamyam singing from time to time. Some of them, such as experimental theater company Zuni Icosahedron, have tried to find new ways to present the traditional performance art form to cater to present-day audiences.

Mathias Woo, co-artistic director and executive director of Zuni Icosahedron, is drawn to naamyam because of its connection to the Cantonese language. "It represents Hong Kong and its very unique Cantonese culture. It's one of the purest and most traditional forms of art and it's the last of its kind. It is still alive today thanks to video and audio recordings like the ones of Dou Wun," he says.

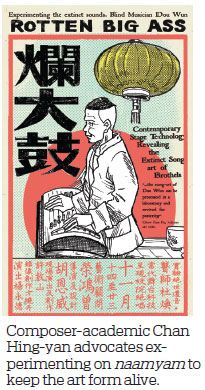

In October, the company put on a show featuring original audio recordings of Dou made in 1975 alongside restored images of his performances. This week they will present a new show titled Rotten Big Ass, named after one of Dou's compositions. Directed and designed by Woo, the production will feature the original recording along with a reinterpreted version that combines elements from electronic music.

"When you use new technology and audio systems to listen to those old recordings from the seventies, they feel very different. I'm very excited to be able to use new technology to interpret these wonderful (works of) music for everyone to listen to," says Woo.

Through these productions, Woo hopes that more people will be able to experience naamyam in its old and new forms. He believes a Cantonese-speaking audience will easily understand and appreciate the art form's uniqueness although it is from a different time.

Gaining currency

Both Chan and Woo see connections between naamyam and some of today's popular music styles, particularly rap. The premise of both musical genres is based in storytelling. Naamyam too can probably draw in the crowds if it was presented in a format present-day audiences could relate to.

Chan is all for experimental adaptations of naamyam, believing a strict adherence to the traditional format will only help "museumize" the art form. He commends the local music group, The Gong Strikes One, for trying to revive interest in the form by producing videos of Hong Kong ghost stories told through naamyam singing.

"Instead of performing in a cheongsam or other traditional clothing, can you play a Chinese instrument or sing naamyam dressed in a leather ensemble? Of course, and I think it (could) be amazing," Chan says. "There are many talented young artists today so if a popular musician tries experimenting with naamyam, it may be a way to keep it alive."

(HK Edition 11/15/2019 page11)