Architect of bold designs

Updated: 2019-05-24 08:06

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

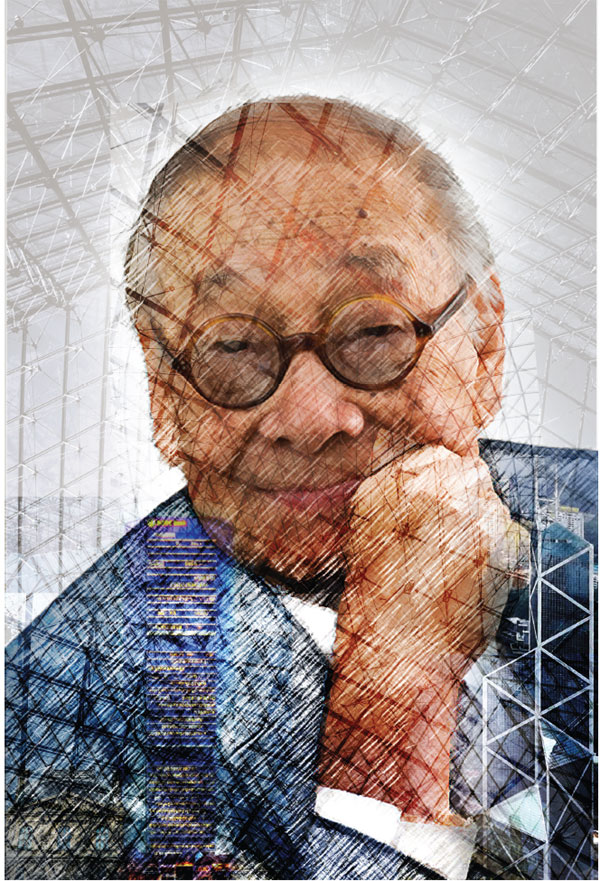

I.M. Pei, the man who designed some of the most iconic modernist structures in China and elsewhere, died last week at 102. Lee Ho-yin remembers his brief, illuminating encounters with the legendary architect.

I have been asked what influence the modernist architect, Ieoh Ming Pei, who died on May 16, had on contemporary architecture. I could probably fall back on my experience as an educator in architectural design and architectural conservation to come up with an answer. However, I think my personal encounters with the master and his works during my formative years as an architecture student would make for a better and more sincere response.

My first indirect encounter with Pei happened when I was a sophomore at the School of Architecture at the National University of Singapore. This was in the early 1980s, an era of aesthetic excess as reflected in the prevailing disco culture and postmodern architecture. One day, a professor introduced Pei's first piece of work in the city state, the OCBC Centre, completed in 1976. Typical of sophomores who tend to favor style over substance, I was not particularly impressed by what appeared to be a rather unremarkable - and drab-looking - office tower. The only lesson that stuck in my clueless mind was an irrelevant side-story that, whether by coincidence or design, the facade of the building resembled the Chinese character denoting the architect's surname.

It was around the same time that the ambitious Raffles City project - of which Pei was the chief architect - had successfully lifted Singapore's status from Third World urban obsolescence to First World modernity. Completed in 1986, the project included the world's tallest hotel and the city's largest shopping mall. By the time it opened in the late 1980s, I was more knowledgeable in architecture, having completed the first of a two-degree program and a year-long intensive internship with two architectural firms in Hong Kong.

I remember visiting the mall's spacious atrium with my classmates and being blown away by what I saw. It was like being immersed in a space that came alive with crisscrossing shoppers on the ground, along the open corridors, and on the bridge spanning the atrium. For the first time I got a sense of Pei's subtle genius and realized what my professors had been trying to drum into my head about creating spaces that would produce a memorable immersive experience.

Culture in architecture

Toward the end of my studies, I had my first direct encounter with the master architect when he came to lecture in our school. As expected, Pei's lecture in the school's largest lecture theater was filled to capacity.

Pei talked about his first project in China, Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing (completed in 1982). He spoke of his struggle to incorporate cultural relevance in the wantonly neutral style of modernism. To accomplish this, as he explained, the architecture had to be infused with cultural familiarity. This was achieved by using abstract Chinese decorative features, and applying the Chinese concept of "borrowed landscape" through framing outdoor landscape scenes with windows and wall openings to form living landscape paintings. No wonder the hotel has become a timeless masterpiece by giving people the experience of physical as well as cultural space.

During the question-and-answer time after his talk, I could not resist the temptation of asking him if there was any truth to the facade of the OCBC Centre being a giant pronouncement of his surname.

Pei gave a bemused chuckle, and said that it was no more than an urban legend. "I am not that egoistic," he replied, "but that is a great story to tell people."

Banking on humor

In the 1990s, after my stint as an architectural designer in several firms, I left Singapore for doctoral studies at The University of Hong Kong. That was when I had my second direct encounter with Pei, when he came to the university to give a talk. At this talk, I learned how Pei was able to use his wits to reverse a seemingly lost situation.

The first story relates to the Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong (completed in 1990) which stands today as one of the city's most iconic landmarks. As with many of his projects, things didn't go smoothly due to the groundbreaking nature of his architectural concepts. The board of directors reacted badly to his design, complaining about the X-shaped structural frames on the building, "You know, we are an important bank, and it doesn't inspire confidence to see a series of Xs all over our headquarters!"

"Crosses? What crosses? Those are stacks of diamonds!" Pei had told them. He wore his trademark Cheshire Cat smile as he narrated the incident to us.

Needless to add, the Bank of China directors approved the design.

The second story is about the Louvre Pyramid in Paris, completed in 1989. In his persistence for quality, Pei wanted near 100 percent transparency in the glass used to build the pyramid. This meant that the material had to be of optical glass quality. But the French glass makers said this was impossible - the best they could come up with was a 90 percent transparency. Not willing to compromise, Pei ran a search and found that there were glass makers in Germany who could achieve his desired standard. Armed with this information, he went back to Paris, and let it be known that he was considering giving the job to German glass makers. Out of national pride, the French government hurriedly assured him that they would try to match whatever the Germans could do.

Pei's design for the Louvre Pyramid was panned in France and by architects the world over. Back then, it was a near-taboo to attach a modern design to an important historic monument. Yet 30 years on, the once universally hated glass pyramid has become a much-treasured modern monument as people came to appreciate how the new architecture has refreshed the otherwise frozen history of the Louvre.

Today, I often say to my students, "Look around Hong Kong at some of the Revitalisation Scheme projects, and you will see the subtle but long-lasting influence of the master I. M. Pei."

The author is associate professor and head of the Division of Architectural Conservation Programmes at The University of Hong Kong.

(HK Edition 05/24/2019 page10)