Printout of the future

Updated: 2018-11-09 06:40

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Science and technology is being hailed as the new engine for economic growth and HK scientists on the Chinese mainland are playing their roles in a low profile. They brought in technology and services in various aspects. Shadow Li met one of them, in the biomedical sector.

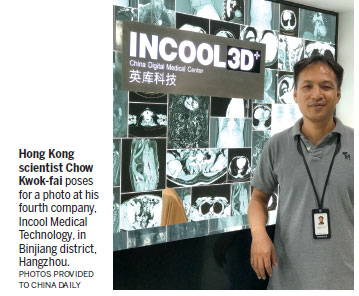

In a startup incubator, still not fully occupied in the Binjiang district of Hangzhou city, Zhejiang province, Hong Kong scientist Chow Kwok-fai is showcasing printouts of bones and organs. The company is a medical startup called Incool Medical Technology.

Chow and his team put up the display in the company lobby, along with information about the patient whose organs and tissues featured in the display.

Close by, nearly a hundred engineers were leaned back in their chairs, each with a computer mouse in hand, and their almost hypnotic movements suggested they were drawing something.

"They are decoding the flat-layered medical images sent to us and using computer to reconstruct models based on the data they've acquired from the images. Then, we print out everything," Chow tried to explain in the simplest terms what he and his team were doing.

Still, in these early days of 3-D printing, what they are doing seems hardly imaginable.

Nowadays, 3-D printing is no longer really novel, but people always seem surprised as the technology delves deeper into reality. The fusion between 3-D printing and the medical profession is right at the top of the benefits available from the new technology.

In the United States, 3-D printing labs are being set up in leading hospitals. In 2016, 99 US hospitals had centralized 3-D printing facilities. In 2010, there were only three labs, according to Materialise, a Belgian company specializing in 3-D printing software.

In China, 3-D printing in hospitals is still rare. There may be occasional stories on the Chinese mainland about how doctors have used printed cardiac veins to replace dysfunctional arteries for patients. Still, it's unexplored territory for doctors and patients on the mainland, despite the enormous potential being demonstrated.

Qianzhan Industry Research Institute, a Shenzhen-based industry consultancy company, estimated that the market size of 3-D printing in China will reach $2.25 billion by the end of this year.

In the newly developed area of Hangzhou and at a new branch in Wuhan, Hubei province, Chow and his crew work with 300 hospitals that are thousands of miles away. Information exchange is via the internet. That is pretty impressive for a small startup with about 200 employees, considering there are about 1,700 top of the line Grade 3A hospitals on the mainland.

"We receive about 30 to 50 cases daily," Chow said, adding that the company became profitable in September 2017, five months after startup.

Thirty-seven-year-old Zhou Yiming, an attending physician, specializes in liver cancer at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital. The public Grade 3A hospital is one of the beneficiaries of the work of Chow's company.

The two men met through a mutual friend. Zhou had been curious about the technology held up as the way of the future in anecdotes he'd heard at scholarly gatherings.

Chow and Zhou started their first collaboration in 2017. Since then, the two have collaborated on over 100 cases.

Medical images

Zhou said the new technology has been of great help when he had to explain surgical approaches to patients and family members.

Zhou is able to show patients a 3-D rendering of their medical situation generated by Chow's engineers. Zhou found the models are the easiest way to lay out the situation to laymen.

"For a patient with a large hepatocellular carcinoma, we have to assess whether it is operable and, if it is, we need to identify the risk," said Zhou.

"That would involve questions about whether the liver could continue to function," he added.

There's more to come. Chow predicted that once 3-D modeling enters the bio-printing phase, it will start a revolution in the medical sector. That revolution will affect organ transplantation, especially. When that day comes, patients will be able to get a liver transplant, using his or her own printed cells. There would be no danger of rejection, he concluded.

For MRI and CAT, it is a 2-D image that contains a lot of data, but still, it is very abstract to the patient and sometimes doctors when planning for surgery.

The data is decoded, and then reconstructed into models to give doctors concise images of medical conditions. That's how Chow works. He offers modeling or even printouts for doctors.

Doctors, with printouts in hand, enter surgery well-prepared, which can save time and even reduce surgical complications, Chow said.

It seems out of character that the soft spoken scientist from Hong Kong, short hair with a gray polo shirt, is actually the principal owner of four companies. He barely talks about anything else except the technology he's developing.

Learning from the best

Chow studied in Singapore before returning to the University of Hong Kong in 2006, where he was invited to work with his professor Joseph Tam Wing-on in a company spinoff from their lab.

Tam was a pioneer in the training of biochemical professionals serving Hong Kong and the mainland. He started back in the 1970s when he returned to Hong Kong to teach at the medical faculty of the University of Hong Kong. Chow was among the last group of graduate students of the renowned biochemical scientist.

"I used to work at hospitals in Singapore and other places before joining Tam's team. Compared with working in the research field, I am more into the application phase, where you can see the results and actual achievement," said Chow.

Joining Tam's company broadened Chow's perspective and opened him up to the possibilities on the mainland.

In 2015, Chow established two more companies - Diagcor Tongshu Clinical laboratory, a third party lab test center, and Zon-diagnostics, which specializes in medical kits and reagents - in Guangzhou, taking into consideration the city's welcoming environment for entrepreneurs from Hong Kong.

The more Chow became engaged on the mainland, the more he became committed to providing Chinese people with value-added technology. He believes doctors and scientific researchers on the mainland are more receptive to new ideas, even if they are still in the development phase.

"I decided I could be the middleman for a technology in transformation since I have been involved in research, production and sales," said Chow.

Cross-boundary opportunities

Hong Kong, with its traditional edge in basic research, is bound to team up with the mainland, which has strong suits in manufacturing and technology transformation. This could be particularly true for the biomedical sector and for people like Chow.

According to a report by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, there were more than 840 million visits to hospitals on the mainland during the first quarter of this year, foreshadowing great business potential for biomedical technology.

The great potential was the main reason Chow set his sights on the mainland when he opened his fourth company Incool in Hangzhou.

Another reason Chow chose to move to the mainland was the abundance of talents. Every year, there are only around 30 to 40 biomedical graduates in Hong Kong, while Zhejiang University, one of the mainland's elite schools, produces more than a hundred biotech graduates from just one class.

Chow is not a well-known figure wherever he goes. He keeps a low profile, but he's created a niche for others from Hong Kong to follow his path to the mainland.

He's also an angel investor, who put money into DropX Biotech - a startup founded by a team of scientists from Hong Kong. The team specializes in cancer-screening but was hesitant to venture onto the mainland. The company founders met with Chow in 2017 and talked to him. Now the company has set up shop in Hangzhou. Chow expected the medical device will be in mass production in mid-2019.

Though he had traveled to a lot of mainland cities, Chow eventually chose Hangzhou as the new home for his company and his family.

Chow's family, including his 3-year-old daughter, immediately got on board with the idea of moving there. The ancient city, where tech giant Alibaba is headquartered, is fast becoming one of the country's leading innovative and creative powerhouses.

"If you asked me to leave Hangzhou for Hong Kong, I don't think I would be able to do it," said Chow. For him, living in Hangzhou is a completely different experience from living in Hong Kong.

Citing the poetry recital he attended the day before, Chow says he has found a work-life balance that wasn't available to him in Hong Kong.

He jogs regularly along the Qiantang River that threads across Zhejiang province. Chow remarks he couldn't enjoy that view in Hong Kong or Guangzhou. He'd be like most people in these two cities, fixated on making money.

Contact the writer at

stushadow@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 11/09/2018 page10)