Haunting memories that endure

Updated: 2018-09-28 07:11

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

As Martin Booth's Gweilo is revived for the stage, Rob Garratt wonders what makes the book remain the go-to expat memoir of HK, year after year.

Recently a British-Australian man filed a discrimination lawsuit against his former boss. Among other things he had accused the latter, a Chinese contractor, of calling him a gweilo - a well-worn term which translates as "ghost man", an allusion to the light skin tone of Caucasian people.

The debate over whether gweilo still carries racist connotations or has evolved into a term of endearment is back in currency, as a result. It seems a good time to revisit Martin Booth's poignant memoir of growing up a foreigner in Hong Kong. Published in 2004, Booth's Gweilo: Memories of a Hong Kong Childhood remains, arguably, the definitive book on the expat experience in Hong Kong, or at any rate the most visible book on the theme.

After he was diagnosed with cancer, Booth, a British writer, spent his final months penning a misty-eyed, cynicism-free recollection of his boyhood years spent in 1950s colonial Hong Kong.

The title likely accounts in part for the perennial domestic success of Booth's work. However, the book opens with a clarification. It states that the term gweilo has evolved into a "generic expression devoid of denigration" over the years. This is easy to believe as expats themselves don't mind calling themselves gweilo - a term which seems to have lost some of its racist connotations.

"It's audacious," says the writer Xu Xi, of Booth's title. "But you know, you can only use an audacious title if you have the right to it, and I felt he did - he can say gweilo and get away with it - somebody else does it and it's pretentious, or a cheap trick.

"A lot of expat writing references Gweilo, because that's the only Chinese word they know," Xu adds.

Justin Santini, the founder of Hong Kong Sacred Spaces, a non-religious organization dedicated to exploring regional history and culture, says he refrains from using the term which he believes still carries a whiff of bad taste.

"We don't know the disquietude (it causes)," says Santini. "(Gweilo's) title restricts it from moving beyond a certain community. There was never a version in Chinese, either in print or on stage - and given its title, I don't think there ever will be."

Santini may prove only half-right. Close to a third of Pants Theatre's adaptation of the book - which returns to the Hong Kong stage this week - is in Cantonese. And while there is no official Chinese translation of the book yet, Gweilo director Wu Hoi-fai has heard that someone in Australia might be working at it.

Mike Ingham, associate professor of English at Hong Kong's Lingnan University, recalls several of his students engaging positively with the memoir over the years.

"I think it's one of those few English language books which really crosses the boundaries between English and Chinese," argues the British expat who has been living in Hong Kong for nearly 30 years. There's a very strong split between writing in Chinese and English about the city, he remarks.

Affinity for Hong Kong

"(Booth) had a sympathy, a love for the place and its people," says Wu. "He doesn't judge straightaway, he sees the whole environment."

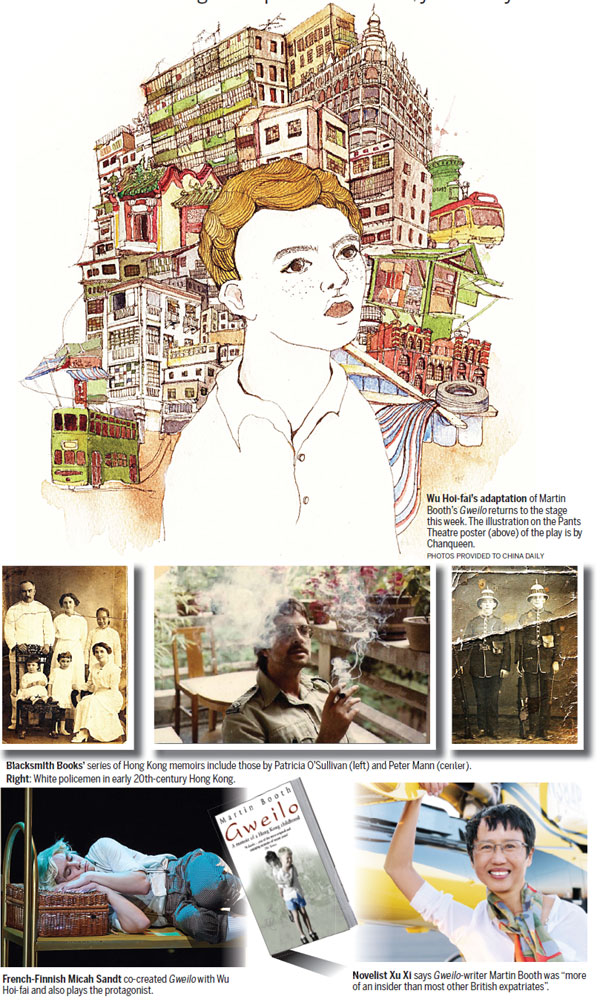

Following an oversubscribed 10-night run in 2016, Wu's adaptation of Gweilo - a one-man-play starring bilingual actor and co-creator Micah Sandt - returns in an extended form this week.

"Growing up in Discovery Bay, the book was in everybody's house. So I picked it up and read a bit - but I don't remember ever finishing it," laughs the 28-year-old French-Finnish actor, whose parents moved to Hong Kong when he was three. "My first impression was 'interesting, this is how the colonials lived'."

While Booth's untroubled upbringing was undeniably the product of colonialism, at the core of his written account is an intimate feel for the streets and those who call them home. Arriving in Hong Kong at the age of seven, he picked up Cantonese readily, and some of the memoir's most affectionate scenes recount his encounters with shopkeepers and rickshaw drivers around his first home in Mong Kok.

"He was much more of an insider than most of the other British expatriates," adds Xu, a former Indonesian national raised in Hong Kong, who like Booth strafed between communities. She came across Booth's work while compiling City Voices, a collection of post-war, English-language writing on Hong Kong published in 2003. She included an excerpt from Booth's out-of-print novel Iron Tree.

"I grew up in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 1960s, and the only British expats who knew Cantonese were priests, some police inspectors, and a few civil servants," she adds. "There's a British tradition of colonialism, of course, this idea of 'them and us'."

Booth's affectation-free, intuitive prose stands out amid other books that use Hong Kong as an exotic setting or historic backdrop. Among the notable English-language entries are James Clavell's Opium War epic Tai-Pan (1966), Paul Theroux's handover portrait Kowloon Tong (1997) and John Lanchester's historical epic Fragrant Harbour (2002).

"Booth has a lot of cachet as a Hong Kong writer," adds Ingham. "Other writers come through Hong Kong and leave - what you feel from Gweilo is his affinity coming across on every single page.

"Maybe it's an overused phrase, but he evokes the spirit of the place. A memoir that can do that, and is not just me, me, me - but about the place and told with great affection and a lot of excellent memories, a lot of precision in the details - that is a bit of a winner. That seems to me why it's done so well."

(HK Edition 09/28/2018 page12)