A momentous journey to nation's future

Updated: 2018-09-07 07:06

By Luo Weiteng in Hong Kong(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

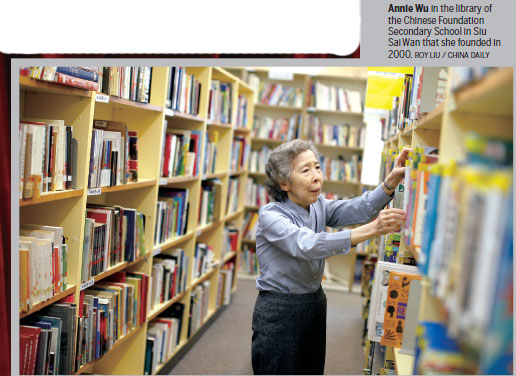

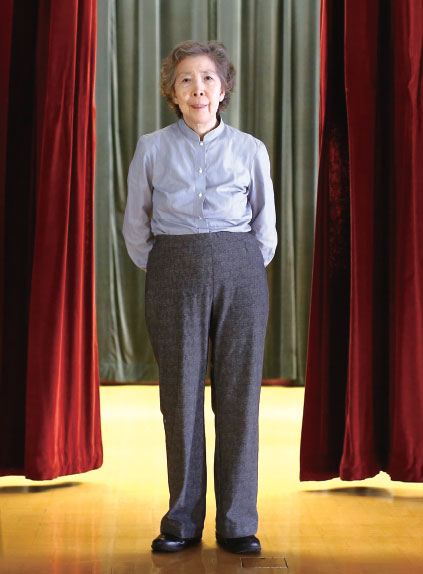

Annie Wu Suk-ching - one of the first Hong Kong entrepreneurs to invest on the Chinese mainland - has lived to witness the historic rise of China from a rustic backwater to the world's No 2 economic powerhouse.

At 40, I no longer had doubts, the great Chinese philosopher Confucius once said.

For Annie Wu Suk-ching - the legendary founder of the Chinese mainland's first joint venture, Beijing Air Catering Co, who has played a zestful role in China's four decades of reform and opening-up - she had no doubts either about the nation's bright future.

As the bellwether of the first batch of Hong Kong-based entrepreneurs who headed north to embrace a daring, near iconoclastic spirit of change, Wu, born and bred in Hong Kong, has seen her life trajectory intertwined with one of the most magnificent episodes of Chinese history.

Her story, bearing the imprint of a nation-wide "just-do-it" push and with the appearance of the so-called serendipity or coincidence in history, began with a search for roots in the eventful and momentous year of 1978 when China launched its historic campaign for economic prowess.

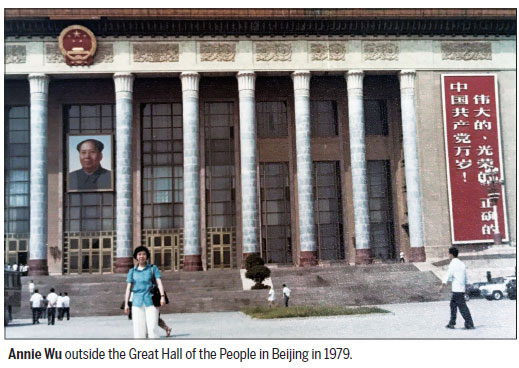

In mid-December 1978, Wu set foot on mainland soil for the first time to catch a glimpse of the motherland that used to be on the lips of nostalgic teachers and between the lines of ancient Chinese poetry. Her maiden visit was to southwest China's Sichuan province - the home to giant pandas and from where the late architect of economic reform Deng Xiaoping hailed.

"For years, I had been like a lone traveler, leading a rootless wandering life and looking for long-lost treasures. When I stepped onto the land of Sichuan, I was overwhelmed with a strong sense of national identity and got a taste of what it was meant to be Chinese," she recalled.

"I found my roots - the treasures that define who I am and where I come from."

At Wuhan Railway Station on Dec 23, 1978, on the journey back to Guangzhou, capital city of Guangdong province, Wu heard a radio address by Deng, who announced gai ge kai fang, or reform and opening-up, with his iconic thick Sichuan accent. She heard the paramount leader, in his determined and clear voice, pledge to focus the nation's total energy and resources on economic development and open the door to overseas investors, including those from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, through joint ventures.

It was an eye-opener. With good business sense presumably inherited from her father James Tak Wu, who founded Hong Kong's largest catering group Maxim's Group from scratch, Wu smelled a harbinger of serious change in the most populous country on earth.

The next year, came the sort of historic opportunity she had been longing for. In the following two years, she would take the good hard road to establishing Beijing Air Catering Co - then registered as "Sino-foreign Joint Venture 001" - that essentially laid the foundation for the creation of more foreign-funded enterprises and put an end to the inflight menu that offered nothing more than biscuits, boiled eggs and cold luncheon meat.

At that time, the reopening and normalization of Sino-US relations put the scheduled passenger airline service between the two countries on the agenda after a 30-plus-year hiatus. The historic move brought the spotlight on the food supplying capability of the Chinese airline industry, raising eyebrows among people from Pan American World Airways, which was chosen by the United States government to operate the US commercial flights to China.

Dismissing the US proposal for stopovers in Tokyo for catering services, Deng was adamant that inflight meals must be supplied at Beijing International Airport to make it a real direct flight.

The Chinese side needed a helping hand to tackle the burning question that presented a stumbling block to the restoration of regular flights between China and the US.

Extensive family experience

Wu believed it was the right time to do something for the motherland. She took the idea of capitalizing on her family's extensive experience in the catering business to help airlines flying out of Beijing to deliver a selection of hot meals for passengers to her father and convinced him.

Wu and her father were next on a wearisome, 13-hour train-and-plane pilgrimage to Beijing for protracted talks with the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) in mid-1979.

The negotiations moved slowly. Without a precedent, both sides found themselves virtually clueless and could only "cross the river by feeling the stones" - the famous saying Deng had coined to describe the process of learning as they go.

"With almost no knowledge of Mandarin, we used facial expressions, gestures and traditional Chinese characters written down on paper to communicate with the officials at Beijing Hotel," said Wu. "A person from the Beijing side knew a bit of Cantonese, and helped out as an interpreter."

Those days, the Chinese government, with the whole existing legacy of a centrally planned economy that must be taken down, had exactly zero experience dealing with foreign investors. Officials did not have the slightest idea of what was legal or illegal, so much so Wu had to translate the contract, letter of intent, and relevant clauses of corporate law commonly used in Hong Kong into Chinese for their reference.

As the deadline set by Deng for May 1, 1980 approached, then CAAC chief Shen Tu could barely sit still. He asked Wu's father if he could start the preparatory work before getting the final nod from officials, many of whom had no concrete idea about joint ventures and dared not give a clear-cut answer.

"Without any contract or letter of authorization in black and white, a handshake with Shen simply meant the deal was nailed down," Wu said.

Out of the firm belief in Deng's foresight and determination, Wu's father raised HK$5 million in Hong Kong - a substantial sum of money at that time - to buy equipment overseas and transport them to Beijing via Hong Kong.

By March 1980, all the equipment had been installed and set for a trial operation. But, an official go-ahead still hanged in the air. When Deng eventually learned of this, he asked, "What does Mr. Wu do in Hong Kong?"

"Catering business," he was told.

"Does he know how to make croissants?" asked Deng, who had lived and worked in France in the 1920s and reputedly developed a strong taste for croissants.

"He knows very well." "Then why not approve it?" Deng said.

On Deng's instructions, the deal finally got the green light in no time. All the paperwork had been in place by April 1980, heralding the much-awaited birth of China's first ever joint venture, with the government taking a 51-percent stake and earning Wu her nickname "Miss 001".

"No one had ever expected we could make it. Both sides treated each other heart-to-heart and shared the weal and woe of the mother country. It was our shared ancestral and cultural roots that fostered mutual trust, sincerity and patience in the months-long negotiations. This ultimately helped Maxim's beat other three bidders to secure the partnership," Wu reckoned.

The historic tale and anecdotes behind the founding of Beijing Air Catering stand as a living embodiment of Wu's dogged commitment to the development miracle that transformed the nation from a bucolic backwater into a modern market economy.

Over the past four decades, Wu had been known as a "backpacker", frequently traveling between the mainland and Hong Kong to facilitate foreign investments in burgeoning mainland cities and help home-grown companies set off for the world.

Such a role bears a striking resemblance to that of her hometown Hong Kong - the "super-connector" having the best of both worlds.

"For years, Hong Kong has played the part of a bridge linking the Chinese mainland with the rest of the world. It's the most classic example of luring foreign capital to the world's second-largest economy, thanks to our cultural and linguistic similarities that have enabled us to do half the work with double results," Wu noted.

Redefining Hong Kong's role

Today, Hong Kong is in the throes of a major transformation, looking to redefine its role in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area.

"In the next three to five years, Shenzhen, the fishing village-turned-boomtown that stands as the poster child of China's economic take-off, has what it takes to become the world's most successful 'Silicon Valley'," Wu forecast.

"It will be Hong Kong offering services to Shenzhen, rather than Shenzhen serving as an economic hinterland for Hong Kong."

Now a bustling metropolis of nearly 13 million residents peering at Hong Kong across the Shenzhen River, Shenzhen will continue to gain momentum from the government's unwavering support and chart its course to becoming the magnet for talents across the country and the world.

"This is where Hong Kong could come in by recruiting a clutch of top minds to pioneer reforms with policy blessing," said Wu.

The entrepreneur, now in her 70s, attributes her "original aspiration" that put her on the frontline of the ground-breaking reform and opening-up to her deep love for the homeland.

Wu's sheer attachment and devotion to the country had its roots years back when she studied at Hong Kong Sacred Heart Canossian College, where she sketched a fainted and original outline of the motherland from Tang poetry, ancient Chinese prose, books about the May Fourth Movement and stories from teachers.

"Since then, at the age of eight, I had made up my mind to see for myself what the Chinese mainland really looks like, and do something for my mother country some day in future."

That resolution propelled her to be a determined supporter, keen contributor and an active participant in China's dizzying economic growth. It also highlights her role as an earnest promoter of the nation's time-honored cultures and traditions.

Wu voiced concern over the decades-long unbridled economic, social and technological development that has made people preoccupied with the materialist way of life, and gives little care to traditional culture.

"The fundamental driving force for realizing the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation lies in the traditional culture," she reckoned.

"Without it, we're like a river without headwaters, a tree without roots."

sophia@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 09/07/2018 page18)