Meeting the invisible enemy

Updated: 2018-08-31 07:22

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Ever since the first case of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) struck Hong Kong in 2004, researchers have scrambled to find the remedy for the deadly flesh-eating bacteria.

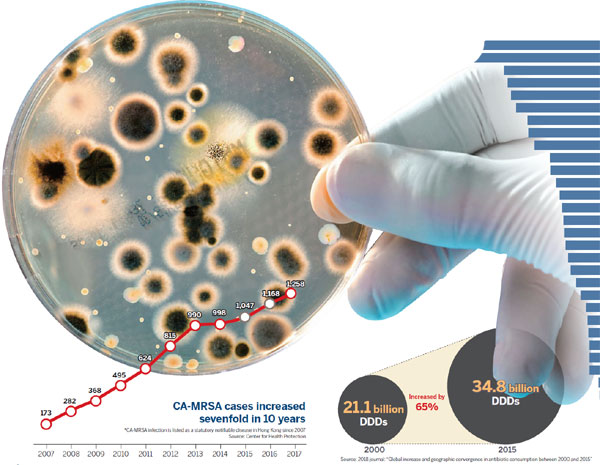

In 2007, the infection attacked 173 people in Hong Kong. A decade later, in 2017, 1,258 people were diagnosed with the devastating malady.

The scourge of MRSA in Hong Kong worsens, as the infection develops resistance to antibiotics which previously had suppressed ordinary staph infections but are no longer effective.

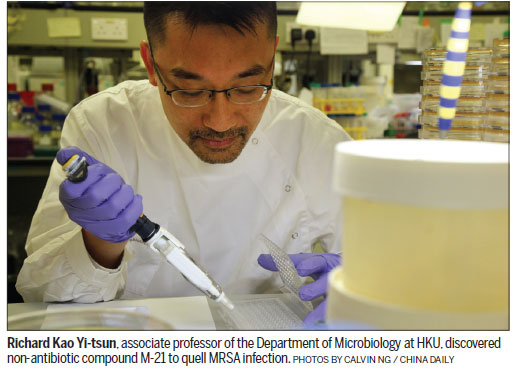

Among those working to defeat MRSA is the eminent Hong Kong microbiologist Richard Kao Yi-tsun. It was he who discovered a compound to defeat SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) that killed almost 300 people in the city in 2003.

Of greatest concern to the veteran researcher is that the treatment of MRSA infection has become more difficult. Even healthy people are at risk.

At a research laboratory at the University of Hong Kong, Kao's tall, rangy physique stands out amid the cluster of several scientists - all immersed in a number of microbiological tests. Since 2009, Kao and his research fellows have worked, sometimes around the clock, to examine how MRSA grows, multiplies, disseminates and sickens its host.

As the leader of the research effort, Kao focused on identifying the virulence factors of MRSA. At the top of his agenda was a formidable pathogen, the evolved strains of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), resistant virtually to all antibiotics.

"There is no one measure effective for controlling drug-resistant bacteria - or superbugs, as people call them. MRSA is one drug resistant bacteria," Kao said, as he dropped tiny beads of bacteria onto a sampling disc.

Though Hong Kong has no official data on the mortality rate of MRSA, Kao determined the data in give and take discussions with frontline physicians concerning MRSA. The lethality among patients with pneumonia is disturbingly high. On average, MRSA causes death in one out of two patients with pneumonia.

"It's a can of worms descended from indiscriminate use of antibiotics. If we don't hurry to find an effective medication to curb MRSA, it's going to be more catastrophic," said Kao, associate professor of the Department of Microbiology at the HKU.

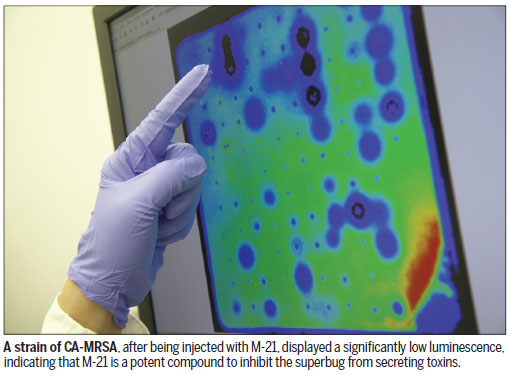

After almost a decade of dedicated work, Kao succeeded in 2018. He scouted out a non-antibiotic compound, M-21, capable of preventing the MRSA from producing multiple deleterious toxins.

M-21, singled out among 50,240 compounds, binds to ClpP and inhibits its activity. ClpP is a protease and a major cause of virulence in MRSA. Kao said ClpP controls the production of -toxin and protein A, the two toxins which ruptures white blood cells and sequester the host's antibodies to help pathogen evade the immune system, respectively. These two factors are major contributors to the virulence of MRSA. "M-21 works as if it hampers MRSA from manufacturing ammunition. It doesn't kill the bacteria but is capable of subduing the virulence inside MRSA," he adds.

"Simply put, we want to use M-21 to make the once harmful MRSA harmless. Then? Leave the 'killing' job to the human immune system," he says.

The hunt for M-21 was long and daunting - yet rewarding. Kao is the world's premiere scientist delving into solutions to fight MRSA through a new lens: a novel approach without antibiotics.

Against the tide

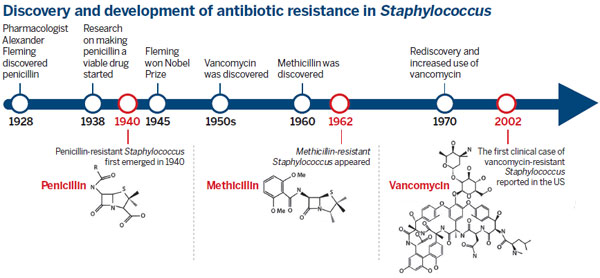

Since MRSA first emerged in the United Kingdom in 1961, scientists worldwide have been on tenterhooks, intent on searching for new antibiotics and trying to outwit the superbug. MRSA, however, continued mutating rapidly and proved highly resilient and many efforts to control the bacteria ended in failure.

MRSA no longer responds to an entire class of penicillin-like antibiotics called beta-lactams like penicillin and methicillin. An aggressive antibiotic vancomycin, which is costly and causes side effects, has been used as the last resort to treat MRSA. The first clinical infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus, though rare, was reported in 2002 in the United States.

In view of that, Kao decided to abandon orthodoxy. In 2009, he set out to go against the prevailing concept calling for new antibiotics to fight MRSA, even before the World Health Organization declared MRSA a "global threat".

"The fight against superbugs resembles 'the tortoise and the hare' race. It's hard for humans to catch up with the speedy hare, in this case, the rapidly changing antibiotics-resistant bacteria," he said. As in the old fable, the best hope is that "slow and steady wins the race".

Antibiotics could kill bacteria, but the tougher, more resilient ones mutated themselves, rending themselves an ability to resist the antibiotics. They then swiftly multiple themselves and took over previous strains. This is how MRSA was bred. Kao wanted to break the circle.

He devised a luminescence signaling system that could indicate the amount of toxins secreted from MRSA - the dimmer the luminescence reading, the fewer the toxins MRSA generates. A total of 50,240 non-antibiotic compounds were tested for their reactions with MRSA. Among them, Kao found that MRSA, after being injected with M-21, exhibited a significantly low luminescence. "This indicates that M-21 hinders MRSA from producing toxins," Kao said.

It's an all-or-nothing game. There was no guarantee that the non-antibiotic inhibitor ever exists. But it did.

A tough foe

To Kao, S. aureus is a stealthy foe. About one-third of people worldwide have some of it residing in their nose or on their skin. This coexistence pattern has been there for decades, and rarely did the pathogen attack the host.

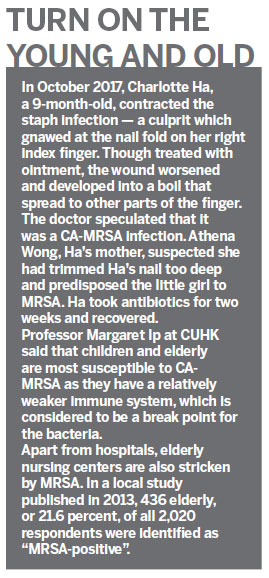

Staph infection happens only when the bacteria penetrates the body, either through a break in the skin like a cut or scrape, or through the digestive or respiratory tract. The infection causes damage ranging from minor skin lesions, like boils or pimples, to more serious conditions like pneumonia, or life-threatening endocarditis, an infection of the inner lining of the heart.

Ho Pak-leung, honorary consultant at Queen Mary Hospital, knows better than most about the perils of MRSA. In 2009, he confronted an intimidating MRSA infection.

The patient, 42, male, sickened by A-type swine flu (H1N1), was also infected with MRSA in the community. This is considered to be the community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). The patient died two days after being admitted to the hospital.

"We treated him using aggressive medications, Klacid, Tazocin and vancomycin (the last resort to treat MRSA). But they were of no help," he recalls. The patient died of pneumonia.

Not only did MRSA destroy lives, it drove up medical costs, mainly due to prolonged length of stay in hospitals. According to a 2013 California study, the average hospital cost associated with MRSA in the state was around $14,000 per case, around twice the cost for other hospital stays.

Previously, most occurrences of MRSA emerged from hospitals or healthcare institutions where infection risks are relatively higher. They are identified as hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA), to distinguish them from CA-MRSA, infections contracted in the community. CA-MRSA is relatively more virulent, tending to develop more serious ailments in patients, Ho says.

Even though the first CA-MRSA case in Hong Kong was officially recorded in 2004, Ho disclosed in an exchange with China Daily that the first case occurred in an 8-month-old child in March 2001. The little boy exhibited a string of severe ailments. He died 26 hours after hospitalization.

Since then, Ho was called on to monitor and scrutinize the transmission of the superbug. He is now chairman of the Health Protection Program for Antimicrobial Resistance in the Centre for Health Protection.

Ho is also a close colleague of Kao's and an avid researcher contributing to Kao's non-antibiotic study. Both medical veterans acknowledge the ever-increasing antimicrobial resistance in CA-MRSA comes down to imprudent prescription of antibiotics.

Most staph infections can be cured by antibiotics. The overuse - and sometimes misuse - of antibiotics helped S. aureus develop resistance to a whole spectrum of antibiotics, Kao and Ho agreed.

Abuse of drug

In the first half of 2018, 632 cases of CA-MRSA infection were reported in Hong Kong, according to the Center for Health Protection. The number of reported infections in the first six months of the year is already 2.2 times higher than all 282 cases in 2008.

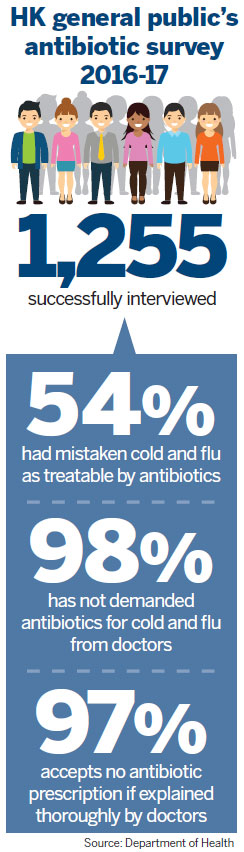

In Hong Kong, the abuse of antibiotics is alarming. According to a 2017 survey by the Department of Health, around 49 percent of the 1,200 people surveyed had taken antibiotics during that year, up from 34.6 percent in 2011.

In a separate study, 97.9 percent of the 1,255 interviewees said they obtained antibiotics from a doctor. The percentage should have been lower, given that merely 10 percent of flu symptoms are caused by bacterial infection, Yuen Kwok-yung, chair of infectious disease at HKU, said last year at a press conference.

Antibiotics act against bacteria but not viruses. So, the high percentage hints that a large number of antibiotics were prescribed to treat viral infections, like common cold, most sore throats and the flu. This contributes to the abuse of antibiotics.

On the positive side, antibiotics have been prescribed as preventive measures. Patients sickened by viral infections have weakened immune systems, which predispose them to secondary bacterial infections. Antibiotics may help intercept that, Kao added.

Margaret Ip, honorary consultant at the Department of Microbiology at Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH), says that the city's public hospitals established a vigorous regulation of antibiotic prescription after SARS. She suspects antibiotic misuse has been rife in the private sector, particularly primary care facilities.

As pathogens keep evolving and become more complex, symptoms between bacterial and viral infections are now more indistinct, Ip told China Daily. "It's possible that doctors in private clinics, without sufficient and updated patient data to refer to, would mistakenly prescribe antibiotic to a wrong ailment," she adds.

Ip suggests setting up an information sharing platform between hospitals and clinics, so that family doctors can keep track of changes in contagious diseases and know what's the best remedy to use.

Currently, the city's private medical practitioners can report antibiotic prescription onto electronic health record system - but it's voluntary. The SAR is using the platform to monitor antibiotic usage in private clinics. But many question the clout of such scheme as rarely would doctors report antibiotic overprescription under a non-mandatory policy.

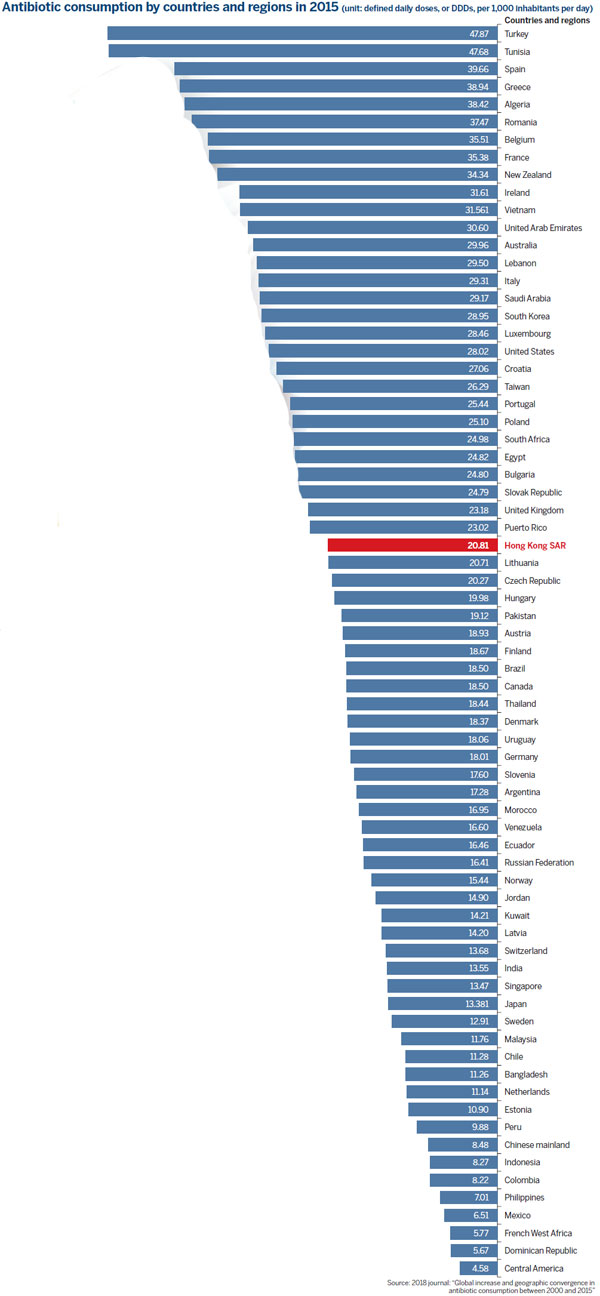

Globally, antibiotic consumption surged from 21.1 to 34.8 billion defined daily doses (DDDs), a 65-percent increase between 2000 and 2015. The findings are based on the latest survey covering 76 countries and regions published this year. In 2015, Turkey ingested the greatest amount of antibiotics, over 47.8 DDDs per 1,000 people per day, followed by Tunisia and Spain. Hong Kong came 30th on the list, consuming 20.8 DDDs per 1,000 inhabitants per day.

The figures show that antibiotic consumption in high-income economies has been more or less constant during the years covered by the survey. The rise in antibiotic consumption was predominantly driven by low- and lower-middle-income economies. Among those, India, the Chinese mainland and Pakistan were the leading consumers in 2015.

Not surprisingly, humans are not the major consumers of antibiotics. A large chunk goes into animals. Antibiotics have been used as treatment for or prevention against disease, or to fatten livestock for market. In 2013, the global usage of antibiotics in food animals was around 131,100 tons, and is projected to rise to around 200,000 tons by 2030.

Over the past few years, the misuse of antibiotics in poultry caused catastrophic incidents. In 2013, a multidrug-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg, linked to chicken manufactured by a single poultry producer, sickened 416 people in the US.

"It's best to ban all antibiotic applications on farms. This, however, will lead to an increase in food prices, and make lives rougher for people with lower incomes," said Kao.

"Hong Kong imports most of its poultry, mainly from the US and the Chinese mainland. In light of this, it's hard for the SAR to impose controls."

Looking on the brighter side, the country's Ministry of Agriculture last year mapped out measures to reduce antibiotics in poultry and livestock. The authorities intend to abolish over 100 high-risk drugs currently used on animals. By 2020, over 97 percent of poultry, livestock and aquatic products on the mainland are projected to qualify as secure food sources with antibiotic residues well within safety standards.

In November, 2017, the SAR mapped out a five-year plan to combat drug resistance. It aims to bar breeders from using antibiotics on livestock, unless the drugs are prescribed by vets by 2022. In addition, the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department will stop issuing antibiotic permits that now sanction farmers to purchase and possess antibiotics used on farm animals.

The recognition

What's more reassuring is Kao's M-21 discovery as shown in lab tests on mice. Laboratory mice infected with CA-MRSA had only a 40 percent survival rate after seven to 10 days. A separate group, after injection of non-antibiotic M-21, all survived.

The breakthrough finding was published this July in a prestigious scientific journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Margaret Ip of PWH supports Kao's approach of employing non-antibiotic compounds to fight MRSA. "In light of today's sweeping antimicrobial resistance arising from antibiotics, the non-antibiotic approach is the way to rein in the problem," she adds. Ip is now exploring natural compounds in herbs like skullcap root and Chinese goldthread to see if they can be molded into new drugs to counter MRSA.

Qian Peiyuan, chair professor of the Division of Life Science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, however, remains suspicious that MRSA may still acquire the ability to fend off M-21, as it did previously with antibiotics. Qian is also a combatant in the war against MRSA. This year, he spotted an enzyme called D-stereospecific resistance peptidases (DRPs). It was identified in many bacteria. The enzyme is the key factor rendering MRSA ability to break down a class of specific antibiotic named peptide antibiotic, including vancomycin.

Kao anticipates M-21 will be manufactured as a medication and put to clinical trial after five years, before being tested on human patients. If it's proven safe for humans - he expects the first line of M-21 to be used to treat seriously ill patients suffering from CA-MRSA.

M-21, Kao's novel concept to temper MRSA with non-antibiotic compounds, is a quantum leap for fighting the antimicrobial pathogens. The accomplishment earned Kao's team first prize at the Innovation Academy Awards at the International Consortium for Prevention and Infection Control last year. The consortium is a leading platform for scientists from over 100 countries to discuss measures to tackle antimicrobial resistance.

"The award demonstrates that global infectious disease experts are giving the nod to our non-antibiotic approach. They see it as a promise possibly to iron out problems arising from rampant drug-resistant bacteria," adds Kao. It's an emotional breakthrough for Kao, who spent 10 years researching for the solution.

Scientists in drug research and invention always see themselves as tightrope walkers. The research process is long, intensive and enervating. A tiny glitch can trip them up.

After a decade, Kao is still walking the tightrope. All he hopes is that M-21 can get through clinical trials and become a life-saving drug.

Contact the writer at

honeytsang@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 08/31/2018 page9)