An Englishman in new China

Updated: 2018-08-03 06:51

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

From teaching at the coalface in Taiyuan to striking gold in the People's Education Press, Bob Adamson has helped shape generations of English learners. Jon Lowe takes notes.

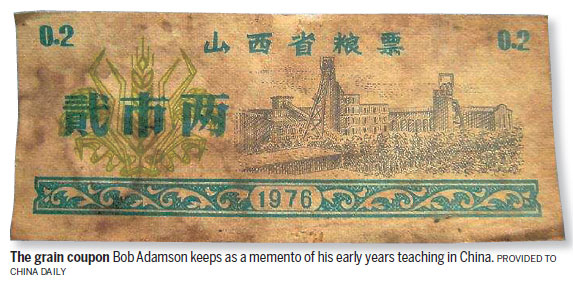

Professor Bob Adamson's nostalgia for his early years teaching in China becomes palpable when, mid-interview, he takes a preserved grain coupon from his wallet - a memento from a "difficult but mind-blowingly interesting" time that forged a love of the country and a career that would see him consult at the highest levels on English and minority education in China.

Now chair professor at the Department of International Education and Lifelong Learning at the Education University of Hong Kong, Adamson first encountered Chinese affairs while studying French at the University of Wales. When a politics major asked him to translate some French articles on China, he was keen to lend her a helping hand. He soon found himself fascinated by the lives of Beijing workers after the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

At an interview with the organization Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) after obtaining his postgraduate teaching qualifications, imagining he'd perhaps go to Africa or the Pacific Islands, "in the waiting room the first thing I saw was a big sign saying 'VSO opens in China'". Adamson duly got a posting.

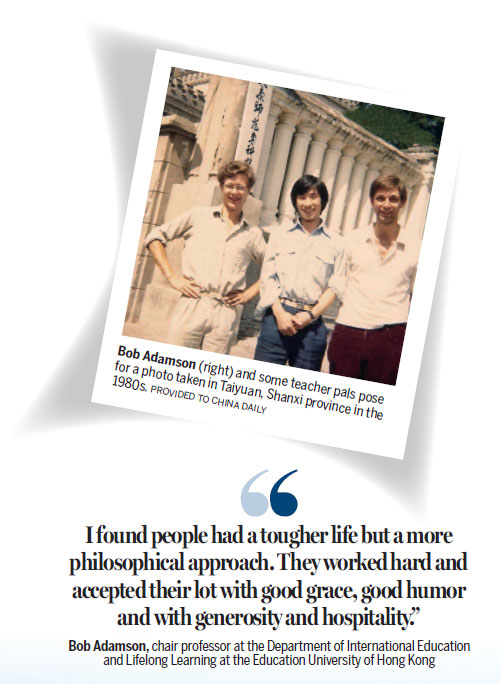

He began training aspiring high-school teachers in Taiyuan, Shanxi province. "It was the blind leading the blind," he says, "but it was a fantastic opportunity". It was 1983. He recalls a new world of ubiquitous Mao jackets, Pigeon-brand bicycles and donkey carts. Renowned for coal mining, iron and steel works, and not a little pollution, Taiyuan was just opening up. Most of the Shanxi province was still closed to foreigners and going outside the city required a travel permit. Thanks to an ongoing "anti-spiritual pollution campaign" it took him six months to get back the music tapes confiscated upon his arrival.

"I remember going to the police station to get my various cards. I had a worker's card, a privilege card allowing me to use renminbi, and" Adamson fishes in his wallet and produces the grain coupon. "We were still on rationing in those days so if I wanted to buy bread or a bun, I had to produce these and pay in cash and in coupons."

His salary was just 200 renminbi (about $30) a month - still a fortune compared to the 45-50 renminbi a month earned by his local colleagues, who nevertheless lived fairly well in work units with subsidized canteens. "I found people had a tougher life but a more philosophical approach. They worked hard and accepted their lot with good grace, good humor and with generosity and hospitality," he says.

Though the city's dozen or so foreign teachers tended to enjoy some luxuries such as hot baths, initially Adamson's group was kept isolated in a converted ancestral home. Cannily, they made the gatekeeper their "grandmother" and she relaxed the rules, turning a blind eye to visitors.

He found himself deeply moved by the way people welcomed him into their homes or invited him out for picnics. He would go to buy a jar of jam and spend half an hour being asked about British jam and other subjects, not least his family. "You'd just have a simple conversation and they would be so interested."

There were also "English corners", then a big thing all over China. A Saturday night in the town square would see up to 200 people practicing their English. "As the silly foreigner I'd immediately be the big center of attraction and that would actually spoil the purpose of the event. So I stopped going to those."

Meanwhile, in class Adamson tried to develop communication, while respecting the preference for laying a strong foundation in grammar and vocabulary. "One of the goals of opening up to English teachers was to address the problem of the 'deaf and dumb English expert' - someone who's only good at writing and reading," he explains. "Once the students got the confidence to talk to me it suddenly came out like a flood."

Mindful that some of his students would be going on to teach classrooms of around 90 schoolchildren, they worked together to tweak the lessons in the school textbooks. It was practical work that would become hugely important to the second phase of Adamson's career.

The next phase

After six years, Adamson came to Hong Kong, looking to develop his career in the region and hopefully start earning decent money. Early on, he heard there was to be a visiting speaker at the British Council. A torrential monsoon rainstorm nearly put him off going, but something made him rouse himself and make it to the talk. Attendance-wise, it was a washout. But for Adamson, it resulted in a fateful dinner encounter.

The speaker that evening was Neville Grant, an educational writer with the publisher Longman. He picks up the story. "I was on my way to Beijing in 1989, and the British Council asked me to give a talk about textbook writing. Bob was among those who braved a rainstorm to come along, and he showed a keen interest. We ended up having a meal together and I recognized him as a dedicated professional educator."

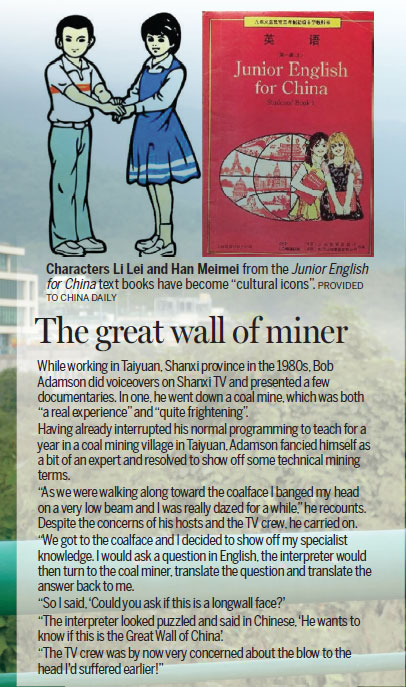

Grant put Adamson's name forward for the textbook project, and soon he was working on the teachers' guides. Junior and Senior English for China promoted cultural awareness and understanding of the West over the ideological criticism of yore. They would go on to be studied by over 400 million students and remain famous to this day.

"It was a real privilege to work on that project. I met fantastic people like Liu Daoyi, a formidable figure in the development of English in China - English in schools over the last 60 years has been largely down to her." While teaching in secondary and tertiary colleges in Hong Kong in the early 1990s, Adamson was also drafted by Liu to do five summer tours of Chinese cities, towns and villages, piloting the famous textbooks.

One day, Liu showed him the archives in People's Education Press (PEP). There on a set of shelves was every English textbook produced since 1949. "I thought, this is wonderful - it's the story of China through English!" PEP was about to get rid of them to make way for a computer lab, so Adamson negotiated a deal to take possession of the collection. "And that was my PhD."

His doctoral thesis analyzed how China's English textbooks reflected political and moral messages and how the education principles shifted over time. "When there's an open door there's more concentration on listening and speaking; when the door's closed the focus is on reading and writing to gain access to the journals and scientific reports." He was even able to interview some textbook writers from as far back as the mid-1950s, "to find out how they navigated the different pressures". Adamson has since opened the trove up for younger scholars to scrutinize. "It's very, very juicy," he smiles.

He has since become involved in improving China's minority education, for ethnic minority students in places like Northeast China and Qinghai province in the northwest who find themselves learning three languages. Ten years ago he helped set up a project to study how trilingual education was being done in mainland primary schools, which grew into a major project with funding from Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland. In 2013 he was awarded the title of "Kunlun Expert" by the Qinghai provincial government in recognition of his work.

His involvement in mainland academic programs has left a chorus of admiring scholars in the country, and when the Standing Committee on Teacher Education was electing new members, one of his former students suggested appointing a foreigner. "That's how my nomination went forward and I got voted on the committee," Adamson says, adding, "It's a nice committee".

At the interview's end, Adamson courteously leads the way to the EdUHK campus exit, pausing to take in the view of the great statue of Guan Yin rising from Tsz Shan Monastery. It's a fitting reminder of the power of benevolent intentions for a man who's helped millions to enjoy the profound benefits of study.

Contact the writer at jon.lowe@chinadailyhk.com

|

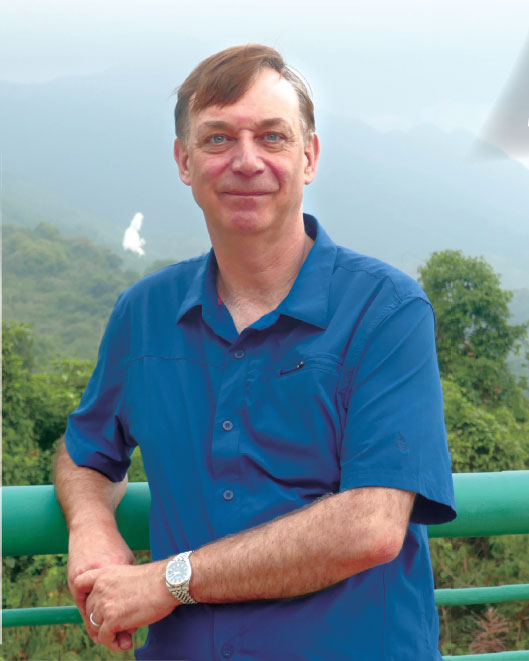

ob Adamson at the serene Education University of Hong Kong campus, with a famous Tai Po landmark in the background. Jon Lowe / China Daily |

(HK Edition 08/03/2018 page7)