Meaning of respect for Basic Law needs clarifying

Updated: 2018-06-12 06:04

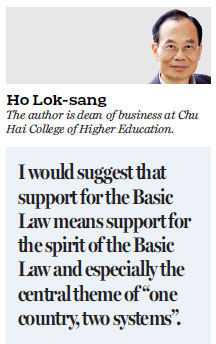

By Ho Lok-sang(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Ho Lok-sang says rigidly following each article does not equate to upholding document's spirit, based on 'one country, two systems'

Over the past few months there has been some confusion over what exactly is meant by respecting the Basic Law of Hong Kong.

Today, candidates bidding for a seat in our Legislative Council are asked to sign a declaration, the first clause of which is that the candidate will uphold the Basic Law and pledge allegiance to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. But exactly what is meant by upholding the Basic Law?

On one occasion, Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor was reported as having said she may not agree to every clause in the Basic Law, which has 160 articles. I have also from time to time commented on the interpretation of Article 107, saying the requirement of balancing the budget should not be interpreted as requiring that we take our revenue as given and committing not to spend "beyond our means" narrowly interpreted as our revenue over a particular period. That narrow interpretation is in particular what is meant in the Chinese version, with the wording "planning spending with full regard to how much is collected in revenue". One legislator challenged her in the Legislative Council as applying double standards to herself and to Professor Benny Tai Yiu-ting, who was criticized for suggesting Hong Kong could consider independence as a state, as several other parts of China, in the event the country's "one-party rule" breaks down.

One commentator wrote an article entitled: "Cause for concern: The law according to Carrie Lam" criticizing Lam's support for co-location arrangements in the Express Rail Link terminal in West Kowloon. He pointed to the Basic Law's statement that national laws, with a few named exceptions, will not apply in Hong Kong. But the co-location arrangements let mainland officials enforce national laws within specified areas within the terminal and on the train. The commentator supported some lawyers' view that the plan clearly violated the Basic Law.

Then there was the case of Democratic Party legislator Au Nok-hin, who won the Hong Kong Island by-election. It was discovered Au had set fire to a copy of the Basic Law back in 2016. The High Court eventually rejected a bid for a judicial review initiated by a Hong Kong Island resident over his qualifications as a LegCo member. The judicial review applicant said Au's act suggested he did not support the Basic Law and that he even advocated Hong Kong's independence.

There is a need to clear up this confusion.

I would suggest that support for the Basic Law means support for the spirit of the Basic Law and especially the central theme of "one country, two systems". Moreover, I would argue that "one country, two systems" must be understood as the relationship between Hong Kong as an SAR and China as the mother country of which Hong Kong is a part. Nitpicking with the imagination that support for the Basic Law means support for each and every clause regardless of changing times, and that legal borders between the mainland and the SAR can never be adjusted for any practical reason, is just nitpicking. It does not help preserve the "one country, two systems" and actually undermines it.

As a policy analyst for several decades, I have long applauded China's pragmatism and willingness to put aside dogmas. In particular Deng Xiaoping, grand designer of the "one country, two systems" framework, had pleaded with all Chinese nationals to put down the debate over whether a particular policy is surnamed "capitalist" or surnamed "socialist". With admirable wisdom and firmness, he advised: "What is important is whether the policy works in improving people's livelihood." This is his famous dictum: "It doesn't matter if a cat is black or white so long as it catches mice."

My question to those who raised all the confusion is this: "Do you want to create problems or do you want to solve problems?" It should be clear to anyone with any sense that no set of laws is ever perfect, so perfect that it need not adapt to changing times. So, why should someone be labeled as not supporting the Basic Law simply because he or she raises some questions over whether a particular clause should be changed or should be interpreted with reference to the needs of the day?

Personally, I do take issue with Au's defense that he burnt a photocopy, not a real copy, of the Basic Law. The symbolic act of burning a copy of the Basic Law should be clear: He did not support the spirit of the Basic Law. This must not be confused with Lam questioning the appropriateness of Article 107 if interpreted as spending without the bounds of the given revenue intake. But I do respect the Basic Law. So I do respect the court's independent judgment in rejecting the judicial review.

I would also say Tai's suggestion that when he was criticized for comments he made in Taiwan that Hong Kong would be "in a state in which (words) can be incriminating". I do not think he will face a criminal charge over his words. People would indeed doubt his suitability as a law professor in an institution of higher learning in Hong Kong.

(HK Edition 06/12/2018 page8)