Nowhere to Age?

Updated: 2018-02-12 06:39

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

The elderly are literally dying in the queue for residential care. Shadow Li finds the government's favored option of aging at?home, supported by community care, needs major overhaul.

When Peter Lam came home that morning after a brief breakfast outing, he realized something was wrong. He knocked on the door to his mother's room. No response. He knocked again. Dead quiet. He pushed it open, only to find what he had dreaded was true - his 80-year-old mother was lying on the floor, unconscious.

Lam called the ambulance. His mother had had a stroke, a bad one. She went into intensive care at Caritas Medical Centre near their home. It was a lucky call he came home early that day, Lam repeated to himself.

But what came next needed more than luck, it required patience and time. Lam's mother was in hospital for weeks. She is now in palliative care service at the hospital. The doctor said even if she recovered, she would lose some of the ability to take care of herself.

Lam knew there would come a day when he had to think about where to put his mother when she recovered. The pair had been living in their two-bedroom flat in Sham Shui Po for years. There was no one available to care for his to-be bedridden mother. The natural option would be one of the public nursing homes sprawled across the city.

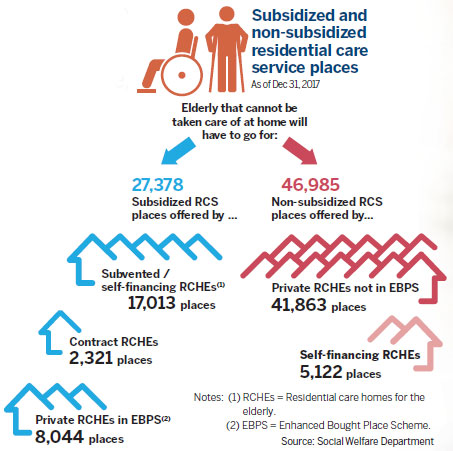

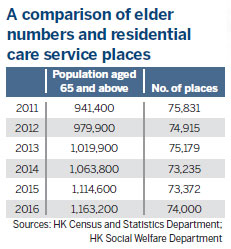

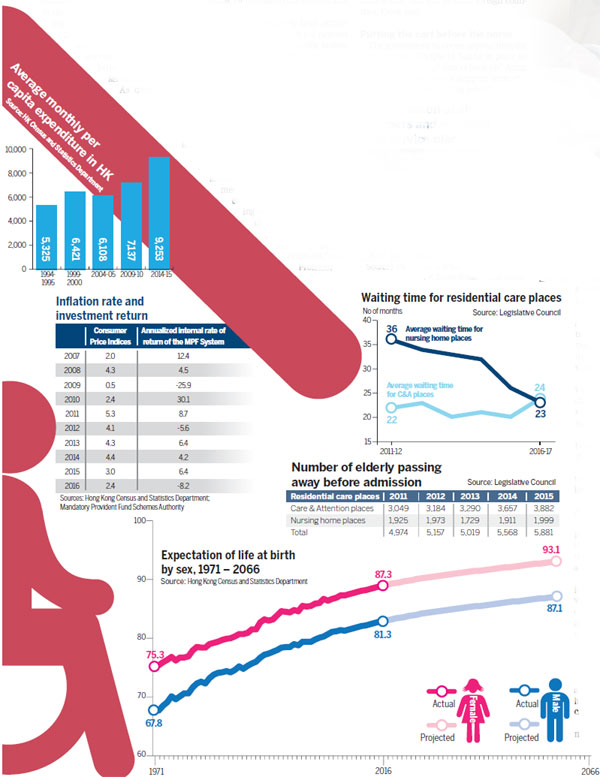

But by the end of last year, the waiting time for a public nursing home could be as long as 39 months, according to the Social Welfare Department, with 36,948 seniors queuing for the service. Many of the seniors passed away before getting a place. The number dying in the queue has grown 64 percent - from 3,392 in 2005 to 5,568 in 2014.

Nursing homes in the city vary in quality, according to an audit report published in October 2014. Public nursing homes, heavily funded by the government, are popular among service-seekers. As demand increased, the government started to offer funded services by purchasing places from private homes. Seniors opting for these homes join a second, shorter queue. Still, the wait takes nine months.

For Lam, even nine months is too long. He needs immediate help once his mother's health improves and is discharged from hospital. He can either choose relatively lousy service for his mother, or wait an unrealistic three years-plus.

There is little available between the two options for Lam. Waiting time for day-care community care services is about the same - 10 months. Home-based care services take longer - 13 months.

Hong Kong has a relatively high admission rate for care homes, with 6.8 percent of seniors being admitted to nursing homes. That is two to four times higher than rates among the city's neighbors, including Japan, Singapore and Taiwan.

Building more nursing-home places has always been on the government's task list. But the city's inherent land shortage has restricted development. A contracted nursing home takes at least five years to build after the Legislative Council grants funding.

"The number of residential-care places provided by the nursing homes is already a record high. The government shouldn't spend too much effort in building more nursing homes. A quarter of the city's nursing homes are public ones, heavily funded by the government," said Professor Timothy Kwok Chi-yui, at the Department of Medicine and Therapeutics at the School of Public Health in the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

In the meantime, more than 80 percent of those who stay in private nursing homes receive social allowances such as Comprehensive Social Security Assistance and disability subsidy, he added.

Kwok is also the director of the Jockey Club Centre for Positive Ageing, a nursing home that mainly takes care of dementia patients.

On average, there is one care-home bed for every 15 elderly people in the city, while the ratio is only half this in some foreign countries, Kwok said.

Putting the cart before the horse

The government has been approaching the issue on the principle of "aging in place as the core, institutional care as back-up". Aging in place requires much support from the community. Following this principle, more community-care services should be provided, instead of residential care.

However, in the 2014-15 budget year, community-care services received HK$1.1 billion, less than a third the HK$3.9 billion spent on residential-care services, according to a survey by LegCo published in December 2015.

This underfunding took a toll on people like Lam, who had to rely on community-care services before landing a place at a nursing home.

"If the community support is strengthened, there is a chunk of the elderly that will not opt for nursing homes," said Kwok, noting that community-care support is the weak link in the elderly-care ladder.

Kwok was referring to such services as meal delivery, household chores and pick-up, or even some visiting medical services for those with chronic diseases.

For those discharged from hospitals, post-hospital care through community support is extremely important and will let the elderly postpone their move into nursing homes.

It's better to subsidize elderly care, instead of pumping money into elderly homes, Kwok said. The government used to subsidize nursing homes to care for the elderly, but that, according to Kwok, will lead to a mismatch of public resources.

"Those who can wait in the waiting list for a long time are those who usually don't need that much care. And those who are in desperate need of care have to drop it and turn to the private nursing homes," said Kwok.

The matching mechanism might aggravate the effect of a growing elderly population, contributing to a snowballing of the long-standing list of seniors awaiting residential-care services.

Currently, under the government's centralized system, the elderly might be considered suitable for a "dual option" of either residential or community-care services. In most cases, the elderly would opt for residential-care services. A University of Hong Kong study in 2009 revealed that the residential-care services waiting time would be cut and the queue would disappear in 2013 if the dual-option mode was cancelled.

That obviously didn't happen. But if the government gave the public confidence by enhancing community-care services, more seniors would be willing to take that option, as it was revealed in many surveys and studies that most of the elderly in Hong Kong would like to stay at home or in the community, which they are accustomed to.

In 2015, the city was shocked when a scandal broke out that seniors at a New Territories nursing home were forced to wait naked on a rooftop before taking showers. The reports sparked criticism and a public outcry for improvements.

After making efforts to improve nursing-home quality, the government started a pilot scheme in March last year to hand out vouchers for residential and community-care services. Seniors can then choose to switch homes or community-care centers if service is substandard. The tactic, dubbed "money-following-the-user", aims to review the current practice of simply giving subsidies to nursing homes while the seniors have no say in their services.

Kwok believes the nursing-home coupon scheme will create a market driven by the elderly, which will in turn boost service quality as private and public nursing homes will compete for clients.

For Lam, there is no easy answer to his problems. The hospital has been asking when Lam's mother can vacate the ward for days. He has been looking for suitable nursing homes, with little luck.

In the end, the backup plan is to place his mother in the nursing home inside the same building he lives in.

Then, at least, when things went out of control, his mother could go upstairs and there she would arrive at a real home. In that way, she could still be counted as aging in place.

Contact the writer at

stushadow@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 02/12/2018 page11)