The sars samaritans

Updated: 2017-06-29 07:35

By Honey Tsang in Hong Kong(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

On the frontline against SARS

Hong Kong tackled the 2003 SARS crisis on a war footing, putting its worst medical emergency firmly behind it in just about four months. A few among those who saw the city's battle against the killer virus up-close and have emerged stronger from the experience share their stories with China Daily.

The battle against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 was a life-changing experience for many. It's changed the worldview of the affected who survived the potentially lethal virus as indeed of the medical professionals who fought SARS from the front lines. For some of them, like Sung Jao-yiu, one among those who led the resistance against the killer disease, the SARS experience was a litmus test of being able to use his medical knowledge with sound sense of judgment. Yet for others, like Thomas Fung Tai-hung, who contracted the disease while offering healthcare to patients, surviving SARS inspired him to dedicate his own career to the welfare of the less-privileged in a public hospital.

The war on SARS wasn't an easy one. For medical professionals, memories of paramedics sprinting to move the ailing into confinement, everyone in surgical masks, speaking in hushed tones, are still as vivid as if it happened only yesterday. Legions of colleagues fell gravely ill, the progression from diagnosis to death coming with breathtaking swiftness.

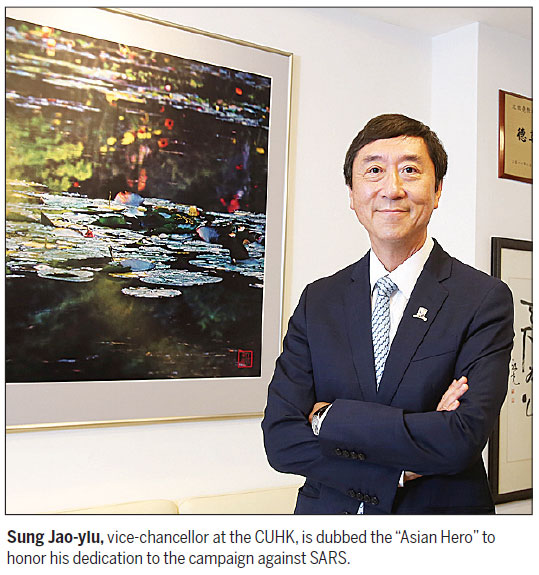

Sung, now vice-chancellor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), sat in his office, legs crossed and seemingly imperturbable, recalling the images embedded in his memory nearly a decade and a half ago. Sung lives with the memories and has made no attempt ever to expunge them.

Sung's part in one of the worst catastrophes to strike Hong Kong in living memory began on March 10. SARS erupted suddenly and ferociously in a ward of the Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH), Sha Tin, New Territories. Sung was chief of service of the Department of Medicine and Therapeutics at the hospital at the time. "That was a Monday morning when I returned to the hospital," he remembered.

"The chief nurse told me that several colleagues had come down with fever and requested sick leave," said Sung.

Eleven healthcare workers from that ward reported sick that morning. All showed symptoms of respiratory tract infection. It was a bad omen to Sung. He was alarmed at the portents of a massive outbreak, later borne out by the epidemic.

Sung ordered Ward 8A closed immediately. Discharge of patients and visiting hours were kept to minimum. Sung had to bear the brunt of a wave of anger from patients and their family members, furious that the ward had been placed in isolation. No one could have foreseen what was to come, not even Sung.

"We were dealing with a mysterious disease. We had absolutely no idea where it came from, how it was transmitted, and how the conditions should be managed in patients," said Sung.

Sung stuck with his intuition, shaped by experience. In the days that followed, his instincts became justified as new infections at the hospital exploded.

On March 11, a day after the ward was quarantined, 50 members of the medical staff reported in sick. Among them, 23 were admitted immediately to hospital.

SARS spread through PWH. By the time the virus came to full cry, 114 healthcare workers, 17 medical students, 39 patients and 42 visitors had been stricken. Among them, 137 contracted the disease from Ward 8A, "Ground Zero" for SARS.

"We were fighting in the dark," Sung intoned.

The sacrifice

Any battle against an invisible, deadly foe must evoke terrible dread. The only defenses were love, grit and professional expertise.

Two days after the outbreak was recorded, on March 12, SARS swept onto the hospital's eighth floor. There would have to be sacrifices. Sung divided medical staff into the "Clean Team" and "Dirty Team". The Dirty Team took care of patients with SARS.

He steeled himself to act as leader of the Dirty Team. He exhorted other doctors and nurses specializing in infectious disease to join him. Those recently married or those with children were directed not to volunteer for the front lines, "because we were not sure what we were handling and how dangerous it could be", he added.

Ward 8A, where SARS patients were kept, became a deathtrap. Still, Thomas Fung, then a medical student at CUHK who had been infected by SARS, felt well taken care of there.

Fung was one of the first group of 23 healthcare workers who became ill. He had been in training in Ward 8A. One of his patients lay next to "JJ", the person later identified as the source of the outbreak on the ward.

Fung could feel the first chill, as the virus took hold. Breathing became painful, then the fever came. A lesion was discovered on his lung, and he was placed in quarantine in Ward 8A.

Fung, now 37, has maintained a close relationship with Sung, his mentor at CUHK back in 2003. He has fond memories of gatherings of medical students at Sung's house, where they enjoyed themselves and talked about their future careers in medicine.

At the height of the epidemic, Sung became the anchor who pulled together the Dirty Team that worked among SARS patients who were desperately ill. Everyone knew the risks, and the high probability of their getting infected.

Clad in gowns, gloves, surgical masks, and with large supplies of courage, front-line doctors and nurses soldiered on, dedicated to saving the lives of those stricken by SARS.

Sung came to check on Fung's condition every day. Tamiflu and antibiotics weren't working. Sung advised him to take steroids. Fung was the first one in Hong Kong to receive steroid therapy in the fight against SARS.

"I agreed to try because I trusted him (Sung)," said Fung.

The steroid worked. Fung's fever rapidly subsided. The lung lesion disappeared in days. In just two weeks Fung was out of quarantine. "I was probably the first SARS patient out of hospital," he said.

The hard lesson

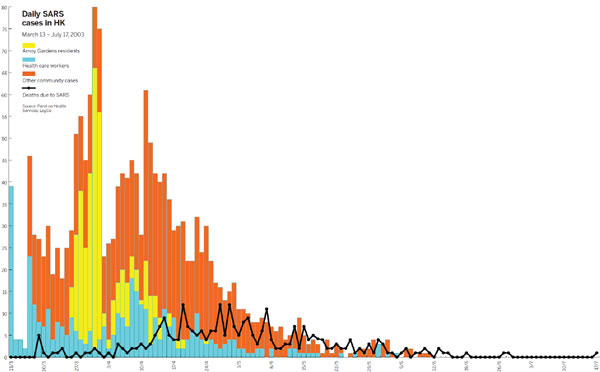

SARS, a coronavirus the infected 1,755 people and claimed 299 lives in the city, began its retreat in mid-May 2003. The number of new cases slowed to a trickle, with fewer than five new cases per day.

Important lessons were learned - albeit the hard way.

"We'd hoped the outbreak could be contained in a few days, but it took about 100 days," said Sung.

Hong Kong's healthcare system had been ill-prepared for the outbreak of a highly infectious virus, admitted Sung. "If we hadn't quarantined people, the disease could easily spread to other places, which it in fact did anyway in some cases."

At the end of 2003, Singapore had 238 reported SARS cases, with 33 deaths. Taiwan had tallied 346 infections and 37 deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

After the calamity, a series of plans were implemented, which Sung describes as "big improvements" in the city's defenses against infectious diseases.

Infection control facilities at hospitals have been fortified. Increased resources were dedicated to the training of more experts in infectious diseases. Most important, said Sung, was the establishment of the Centre for Health Protection (CHP) in June 2004. CHP is charged with overseeing and controlling the spread of infectious diseases.

The SARS virus sprang from Foshan, Guangdong province, where the first case was reported in 2002. The virus went underground, before being imported to Hong Kong on Feb 21, 2003. An infected medical doctor arrived in Hong Kong from Guangdong and checked into the Metropole Hotel, Kowloon. In less than two weeks he was dead.

JJ, a local resident, visited the hotel and contracted the virus. He was admitted to PWH on March 4, the day the doctor from Guangdong died. SARS then took hold at PWH and soon spread to engulf the rest of the community.

Today, communication between infectious disease experts from the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong has improved. For instance, said Sung, the avian flu in recent years was managed more efficiently as a result of better cross-boundary cooperation.

"We (medical professionals in Hong Kong) got the information on the same day, whenever new cases were reported. We were also given more data, descriptions about the nature of the avian flu outbreak," Sung added.

Pass the good on

Fourteen years since the SARS outbreak, Sung's energy can outlast that of his younger colleagues even now. He maintains a rigorous running routine, without exception, even when a typhoon Signal 8 is up.

He stays strong, and devotes his energies to higher education, especially in the medical sector. "I have a deep conviction in the importance of education, because SARS calls for not just knowledge, but also professionalism and ethics in medicine," Sung said of the life-changing impact SARS has had on him.

The SARS lesson led Sung, now considered an "Asian Hero", to take up the challenging position as vice-chancellor of CUHK in 2010.

He's rallied around medical students at the university, prodding them to start their careers in overstressed public hospitals, where the Hospital Authority needs another 250 doctors to fill the shortage in medical staff.

Thomas Fung, a SARS survivor, is now an ear, nose and throat specialist at the Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. "With Sung's encouragement, I have stayed in a public hospital to serve severe cancer cases, and people unable to afford expensive and sophisticated surgery," Fung said.

Fung has also done volunteer work at CUHK. For the past five years he's tutored medical students in anatomical dissection.

"I wish to pass my knowledge to future doctors," said Fung, who says he lives by Sung's creed. These are far-reaching influences SARS has had on the whole city. Painful at first, but profoundly motivating in the end.

Sitting in his office, Sung was the picture of calm assurance, a man who is no stranger to the hazards of his profession. The statues and framed drawings honoring his work help to reinforce that peace of mind and inner strength that helped to defeat the epidemic that left its indelible mark on Hong Kong.

honeytsang@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 06/29/2017 page6)