Teddy Chen: Finding his direction

Updated: 2017-04-07 08:00

By Wang Yuke(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

The feted filmmaker behind Bodyguards and Assassins reveals how a troubled childhood and the no-nonsense approach of some legendary employers forged his meticulous plan to his craft, writes Wang Yuke.

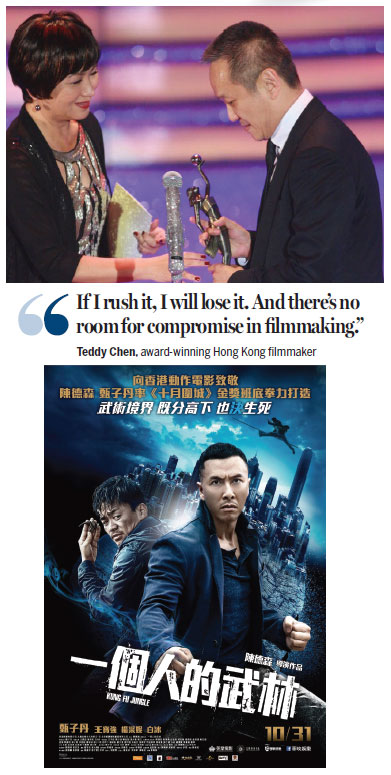

As director Teddy Chen Tak-sum collected his eighth award on the night of the Hong Kong Film Awards in 2010, he looked out at the roaring crowd and remembered the hell he'd been through to reach such a career pinnacle.

It all came about during production of his film Bodyguards and Assassins. He planned to build a town resembling Hong Kong's Central of the early 1900s. It didn't go well. There was the red tape. He had to have the plans approved by the government and that might delay the project for more than two years. So he relocated to Shanghai, planning to build his set in the western part of the city. However, his biggest financial backer committed suicide. The man's money was frozen in probate. Chen had no access to the money and found himself facing a lawsuit. His mother in Australia, hearing of Chen's misery, suffered a stroke, from which she died. His sister was diagnosed with cancer and Chen himself was in a car crash. He fell into a deep depression.

"I shut off the phone, unplugged my landline, drew the curtains, and imprisoned myself in the bedroom, curled up in the corner... didn't even step out of my room to take a bath. When I felt starved I would text my domestic helper, telling her to put the food outside the door," he recalled.

He was on medication. That helped - a bit. But it was a friend who saved him, recommending that Chen attend a religious event at which leaders from Buddhist, Christian, Islamic and secular groups shared the stage in a panel discussion. Hearing the speakers became an epiphany for the nearly broken director.

"Although those religions hold varied and even opposite beliefs, they have one thing in common," Chen continued. "Religions are just a tool to guide you through life. But you can't bank on anything or anybody but you - yourself - to walk down the path of life."

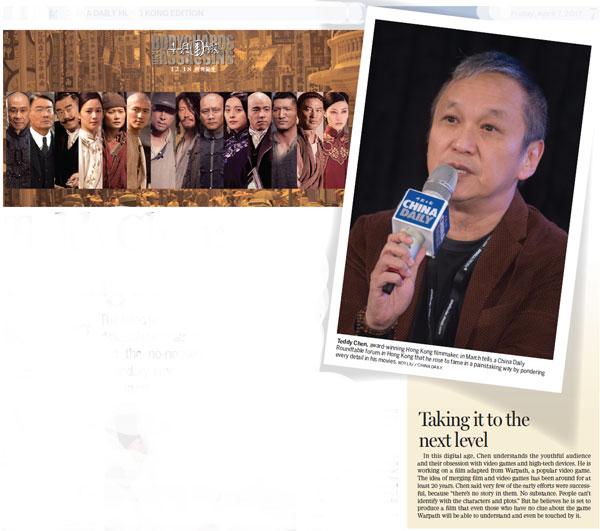

So he pulled himself up and carried on. By then his masterwork had languished for seven years. But he came at it with a renewed vision and restored vigor. World-renowned director Peter Chan Ho-sun (American Dreams in China, The Warlords) saw the proposed film's potential and offered to help. Bodyguards and Assassins became a big-budget film - 150 million yuan ($22 million). A third of the budget went on building the town that would serve as the main set.

For the eight awards bestowed on Bodyguards and Assassins at the 29th Hong Kong Film Awards, Chen had paid a heavy price. It was named Best Film, earned the awards for Best Cinematography and for Best Action Choreography, and Chen himself was named Best Director.

The film is set in the bustling metropolis of Hong Kong during the Xinhai Revolution. In 1905 Sun Yat-sen arrives, laying out his plans to overthrow the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). What Sun has in mind is no secret and people are out to assassinate him. Around Sun gathers a tightly woven knot of revolutionary supporters from all walks of life. They are Sun's only defense, the people keeping him alive.

It is a fictional tale. Sun never appears in the story. In Chen's words, the town is the soul of the film; the storylines are threaded together around it.

"Setting plays a pivotal part in a film. It immerses the audience into the scenario and brings the actors into context. A good setting can give an audience the feeling that their eyes are eating ice cream," Chen said.

Reflecting on his success, he noted that he's not a prolific filmmaker because he likes to do things slowly. His other exceptional works include Kung Fu Jungle and Wait 'til You're Older. He does not tolerate even minor flaws or omissions in the films he makes. "If I rush it, I will lose it. And there's no room for compromise in filmmaking."

Treating every single step throughout the production seriously and carefully is his way of building trust in the audience. "Today's audiences are intelligent and judgmental. They can detect tiny mistakes," he said, citing the example of a skyscraper nudging into shot in a story about old China.

Chen smiled as he recalled what really gave him the drive to become a top filmmaker - working as the assistant to the already famous kung fu star Jackie Chan when Chen was still a teenager.

Childhood dream

Initially, films had been his refuge and solace - as they are for many kids from broken families. He said he didn't work hard in school, though he earned some praise for his Chinese essays and some were even read out in front of the class. Even then he was unorthodox. There was the time his teacher told the class to write an essay on the topic "my father". He wasn't on good terms with his father so he wrote an essay on "my mother" instead. Chen was no great scholar and he had to learn to work hard. But looking back, he said, not having a happy family and not making it to university proved to be blessings in disguise. His distressed family life and the hardships he suffered in his career toughened him up. But even more importantly, they gave him inspiration that he described as originating "from life but higher than life, which audiences can easily relate to".

He would run off to the movies whenever there was a quarrel at home, and there he found his escape in dinosaurs and the even more ferocious denizens born of imagination. "I walked into the cinema in tears, and walked out with a smile. Sadness had magically gone." In that magical refuge, a future director was being shaped. Being from a well-to-do family did have advantages. He got extra pocket money from his mother as compensation for his miserable home life.

He fairly giggled as he recalled the time he and another boy bribed their way into the Shaw Brothers Studio for an afternoon of playing with prop weapons. "We brandished swords, mimicked kung fu stars, jumped onto the (prop) horses' backs pretending to be warriors," he said with enthusiasm.

Then one day a crew member came over and said to him, "Hey, little brat, you're not bad. Interested in being an extra? You can earn some money." Chen began to play roles such as passerby, onlooker, tea-house guest and even a corpse. "It's fun playing a corpse and it paid more because few people liked to do it," Chen laughed. The next step was to fight with wooden swords in the background of scenes. He's been working his way up ever since.

Thus, Chen had been around films before meeting Jackie Chan, acting as a film extra, log keeper and then coordinator. Then the martial arts star offered him the position of assistant director. Chen was 19. "I was not so much an assistant director as a personal helper. I took care of his chores, entertained his fans and ran errands while his house was being renovated."

But soon enough, Chen wanted to move on. He told Chan he wanted to resign. "That night, he (Chan) drove me to a place where couples who want to break up often go. It's amusing, isn't it?" Chen laughed.

Chen thought his talents were being overlooked. He wanted bigger things. "On the way, he (Chan) asked me why. I murmured, 'I want to be a director.' I didn't dare to look at his eyes directly, so I glanced at him in the rear-view mirror. What I saw was a dismissive look as if he was challenging me, 'You? A director? How come?'"

The remark jolted Chen. "He told me, earnestly and seriously, that I could never become a director unless I started from the grassroots level."

Staying true to the original

It took 20 years but Chen became one of the most prominent assistant directors in Hong Kong, alongside well-known names like Stanley Kwan and O Sing-pui. He felt like he was on top of the world - until another life-changing event came like a slap in the face under the penetrating stare of renowned director Tsui Hark (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, Flying Swords of Dragon Gate). "I remember one night after we finished work and were about to leave, he (Tsui) turned to me and said coldly, 'Are you rookie?'" At that moment Chen recalled feeling like a near-sighted frog sitting in a well. Another wake-up call.

Chen said Tsui's perfectionism swept over him and shaped his attitude toward working. "He is a whimsical thinker and likes impromptu creation. He often made a fuss about minor stuff." For example, Chen recalled, an undesired red hue in a prop could send Tsui into a fury. As an assistant director, he had to use Tsui's way of thinking to ponder every detail in advance.

The scars of the depression that afflicted him while creating his most successful film are still there. Now, he said, he understands how to stop negativism from taking hold. "It occurred to me that life is as simple as a train station, where some people come and some go. What I experienced during that trying time is already a good script for a drama," he shrugged, laughing.

Contact the writer at

jenny@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 04/07/2017 page7)