Don't send a boy to do a man's work

Updated: 2017-03-10 08:01

By Wang Yuke(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

It's a matter of what can be done and what needs to be done. Industry is raising its voice about the growing mismatch between on-the-job demands and the abilities of today's graduates, Wang Yuke reports.

A source of enduring perplexity among the drivers of the Hong Kong economy is the questions: Why does local education persist in training for tomorrow and what was needed yesterday?

There is a mismatch between the skills needed by commerce and those of graduates. Some experts contend the solution lies in better communication between those in the ivory towers and those wielding the pointy end of the stick in business.

Calvin Lam, founder and chief executive officer of Masterson Technology Limited, put it bluntly enough. New employees don't have the skills he needs. Instead of contributing to production flow, the new employees become a drag, he says. Lam says the new employees can't get the ball rolling on projects to build his company and secure profits.

Lam's company is a consulting partner to Amazon Web Services (AWS). Cloud computing is their game. Lam's company comes up with solutions for clients who use Amazon's services, so that they can run their apps, manage their content delivery networks, data storage and so on. It requires a high level of competency and experience in cloud computing. Finding such people isn't easy.

Careful as he has been with recruitment, Lam complains there's still no shortage of duds. He's hired new staff who can't do what's necessary in specific areas of the work. So he has to teach them from the ground up. There's a lag of about nine months before each new trainee can work effectively, Lam said.

It was costly, a waste of human resources and a liability for profit-making companies, Lam acknowledged.

Learning lag

Under present circumstances higher education in Hong Kong, in its myriad faculties, doesn't consult business leaders about skill sets for different occupations, noted Reuben Mondejar, a visiting associate professor of the Department of Management at City University of Hong Kong.

Industries, from hotels to banking and retail sales, have their trade associations and they all get together for meetings and conclaves about what their industries need. But communication among schools and the associations isn't happening, leading to the exasperating skills mismatch prevalent among many industries today. Employers can't find the right candidates coming out of tertiary education.

In technology, of course, things change so fast that trying to get a clear picture of what's next is like being spun on a merry-go-round. There are changing demands and skill sets. New skills come, old ones fade away. Every field has a different set of demands and those demands change quickly and often. It fell to universities and other institutions to keep abreast of the changes so that students made the smooth transition from higher education to the workforce, said Mondejar - a belief echoed by many others.

Lam's recruitment needs are different from what they used to be. There's a tool banks and other major companies relied on in days of yore. The gargantuan thing called Documentum functioned as a content management tool for storing and protecting data, Lam said.

Since the dawn of cloud computing, Documentum and many software systems once considered de rigueur have been eclipsed. Now Lam is on the cloud. He wants recruits with Linux experience and AWS certification, a qualification as a solution architect, system operation administrators and developers in computing.

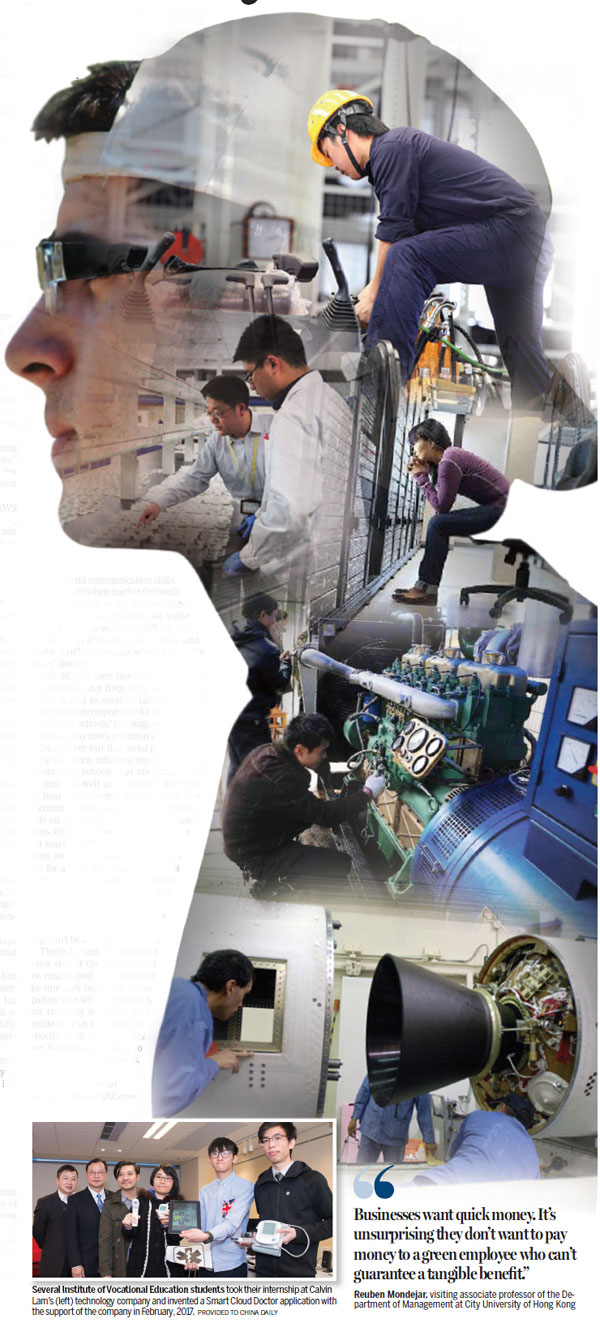

The standard for better cooperation and integration of ideas between industry leaders and educators may already be in place at the Institute of Vocational Education (IVE). It's considered the leading vocational training provider in Hong Kong. IVE asks business stakeholders to be active in curriculum guidance and program design.

At the start of the school term, teachers meet with employers and industry representatives to learn about trends in their respective fields of interest. Teachers update their knowledge and then pass it on to their students.

Stanley Wong Pak-kwong, senior lecturer of the Department of Information Technology at IVE, said the new knowledge acted as a guide for adjusting course content according the needs of the job market.

Teachers and student representatives go to off campus seminars for more learning about technologies and trends. This provides more intelligence that can go into curriculum planning.

Lam states his preference for recruiting from the IVE. He calls it a "safe choice" when graduates have already nailed the basic skills in cloud computing. Some even have AWS certification.

The institute participated in the AWS Academy project last September, giving them access to information on demands as they change. Courses in Linux OS have been compulsory at IVE for some time now.

"I learnt something about the Amazon service system in school. I felt self-assured at work," said Lam Wai-kei, a second-year student doing an internship. He picked up and honed some new practical skills in programming during the internship.

The education mismatch works both ways, says Mondejar. Some companies don't want to work closely with schools. Many small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) fall into that category. Usually schools want payback by way of internships for students when there is that kind of collaboration.

"Businesses want quick money. It's unsurprising they don't want to pay money to a green employee who can't guarantee a tangible benefit," contended Mondejar. "It should be the other way around."

Mondejar believes universities and vocational training schools should pay companies that are providing training for students. He also suggested the government should provide more financial support for employers who offer training for students.

Profit vs principles

Associate Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong Lai Man-hong, who specializes in education policy and management focusing on research in higher education and in vocational training, is skeptical about schools getting into cozy relationships with industry. She underscores the fact that businesses want profit.

The influence of business on syllabus planning can be peppered with vested interests and the profit motive, she argues. Lai worries that universities could be at risk of becoming too job-oriented and deviating from their core mission to enhance the general competency of their students.

Gerard Postiglione, chair professor from Faculty of Education of the University of Hong Kong, shares Lai's concerns. His research interest is in graduate employment and the sociology of Asian institutions of higher education. He highlights that various surveys on employers' attitudes have consistently shown dissatisfaction with the quality of graduates not just in Hong Kong but everywhere.

The discontent, Postiglione argues, comes down to employers' obsession with profits and a disinterest in the essential nature of learning. "Universities are not institutions for helping business make money. Businesses would prefer that universities use public money to prepare students for their businesses," he said.

Lai believes that the competencies to identify problems and solve them, to learn and to transfer knowledge, are the goal of education - as well as other soft skills like adaptability, flexibility and communication skills.

"In this age when market demands change fast and so do skill requirements, the types of talents we value today are those who can pick up new professional skills in a short time and make quick responses when problems arise," she said.

Variability is even more marked in SMEs because they can frequently veer from one niche market to another, Lai stressed. "So, companies are responsible for skills training, rather than schools." She suggested vocational schools pay more attention to soft skills.

Despite her fear that social partners could have too much influence over teaching and training in schools, Lai encourages universities as well as vocational institutes to hear the concerns of employers. She recommends that educational institutions rely on professors from their own business schools for advice and guidance on teaching. "Many professors have been working in business and industry for a long time. They have built large contact networks with industry partners. More importantly, they are able to weigh and balance the views from business stakeholders to ensure that teaching and training won't be disrupted," she said.

There is, then, a consensus view that if the balance can be maintained it is bound to be mutually beneficial. Companies give schools feedback on training students and students can leverage job-specific skills to add profits for business and even to advance their own careers.

Contact the writer at

jenny@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 03/10/2017 page7)