A brush with the world's finest

Updated: 2016-12-08 07:35

By Chitralekha Basu(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

A rich variety of art from home and abroad arrived on the city's streets in 2016. But is HK ready for a public art revolution yet? Chitralekha Basu writes.

Hong Kong has probably covered some distance since the time gilded dragons, massive AIDS ribbons and glazed bronze figures of chubby-cheeked children reading in parks were among the most visible examples of art in its open spaces. 2016 was a particularly eventful year for public art in Hong Kong. The city got to sample works by some of the world's finest - the exaggeratedly curvaceous bronze figures by Fernando Botero, the spear-headed, geometric, semi-abstract sculptures by Lynn Chadwick, the neon-illuminated images by Vhils erected in Pier 4 in Central, mimicking the iconic buildings along the harbor front.

It is a good year in terms of locally produced public art as well. The Hong Kong MTR commissioned well-known artists from the city - Heung Kin-fung, Lam Tung-pang and Benson Kwun - to spruce up some of their stations. University of Hong Kong's (HKU) Centennial Campus acquired a Danny Lee sculpture - his fun take on the clouds and mountains in traditional Chinese ink paintings. Between late December and January 2017, Oi! Street Art Space will run a program in which four Hong Kong artists will each manipulate the spaces inside a century-old structure assigned to them, creating site-specific art on the basis of research and an application of personal aesthetics. The audiences who step in these made-over spaces will, simultaneously, be a part of the art project even as they experience it.

|

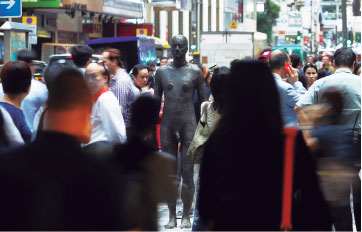

Antony Gormley's bronze nude drew flak for obstructing pedestrian traffic in Central. Roy Liu / China Daily |

Evidently, there is no dearth of public art events in the city's cultural calendar. But then, is Hong Kong ready for a public art revolution yet?

Meg Maggio, director of Pkin Fine Arts gallery, credits the city's property developers with preparing the seedbed for arts education by allowing public access to art objects from their collection. "In some places the government offers a discount if you make space for art, but in Hong Kong property developers do it without any such incentive," she remarks.

Some do this with flamboyance, flaunting their prized acquisitions from the atriums and passageways of their properties, as New World Development seems to do with their Damien Hirst and Deborah Butterfield sculptures at the K11 art mall. Some others prefer to keep it more understated. Hong Kong Land, for instance, has put Salvador Dali's Woman Aflame in a relatively inconspicuous corner beside the escalators in Alexandra House, and a generic Henry Moore, The Double Oval, in the patio of Jardine House. And yet others have a more lighthearted approach. Tracey Emin's neon sculpture, My Heart is With You Always, for instance, was temporarily pinned to the faade of The Peninsula Hotel in 2014, forcing classical 19th-century rococo style architecture to co-habit with kitsch.

|

The Gormley nudes installed on un-walled terraces confused some people even as they served as an introduction to public art. |

And yet, public art is so ubiquitous in Hong Kong, they often fail to get a notice from the passersby on the run. "It's actually quite difficult for public art to be noticed at all in Hong Kong," says Stefan Al, who had taught at HKU's school of architecture. "There are skyscrapers, so many LED screens, busy traffic, hundreds of people, and all the shop fronts. And art has to compete with all of these. Maybe it's not so much an issue of whether Hong Kong resonates with art. The choice and placement of art is not always optimal for noticing these."

The Gormley nudes

The 31 life-size bronze figures by British sculptor Antony Gormley, installed on the rooftops and pavements of Hong Kong for three months in 2015-16, however, jolted Hong Kong's residents out of their apparent indifference to public art. The Gormley nudes created a resonance alright, although there were one or two discordant notes as well. The local police station in Admiralty received quite a few calls from people who assumed the dark figures standing on un-walled terraces in the dead of the night needed help. A temporary barrier had to be erected around the figure standing on a sidewalk in Central after someone complained it was obstructing pedestrian traffic. At the end of the day, the Gormley nudes had, however, successfully started a conversation about the inter-relationship between public art and civic responsibility and their mutual jurisdictions.

|

The Gormley nudes installed on un-walled terraces confused some people even as they served as an introduction to public art. |

It was not the first time naked life-size figures placed in public view had stirred mixed feelings in Hong Kong. The artist Lam Tung-pang remembers public outrage over nude sculptures a store owner had put in a display window in the 1990s. In 2016 the protests were not on account of obscenity.. This time people were offended because art got in their way, trying to shake them out of a comfort zone of having to deal with the routine and familiar.

"People have certainly become more accepting, but these changes are happening slowly," says Lam. "I think it's good to have even people who find nude sculptures offensive to be talking about it. Such argument provides more perspectives on public art, especially if the arguments are constructive ones."

Pauline Foessel, who runs the non-profit Hong Kong Contemporary Art Foundation, thinks the temporary fencing got the Gormley sculptures more attention, which was a good thing even if it were for the wrong reasons.

But didn't the yellow railings ruin the intended look of the sculpture?

The possibility of such unforeseen consequences, says Foessel, is written into the contract for those involved in public art programs. Having curated two significant street art shows, by Shepard Fairey and Vhils, in the recent past, Foessel is only too aware of the ephemeral nature of such projects. "If you want to put a work of art out in a space that does not have control of an organization or an artist, you have to know that the piece will be more vulnerable and exposed to potential damage. Any artist creating a mural knows it is not going to last very long, certainly not for ever and that's the beauty of it as well."

Up, close and physical

Lee Ho-yin, head of architectural conservation programs at HKU, would in fact not call something "public art" unless viewers are able to get up, close and somewhat physical with the piece. He recalls how the giant spider-esque sculpture of a dancing figure erected at the entrance of Langham Place on Argyle Street would be jealously guarded by security men until recently, which didn't seem to make sense. In Lee's opinion, even the Bruce Lee sculpture in Tsim Sha Tsui, probably the most representative of Hong Kong's pop culture history, would have been more effective placed closer to the ground level, for people to put an arm around the martial arts hero if they so wanted.

"Public art in HK is still treated as something very precious," says Lee. "Usually they are mounted in a way that you cannot or are supposed to not touch these. That sort of defeats the point of public art. This suggests whoever is in charge of managing public art projects are not making a distinction between public art and art that belongs in a museum."

The attempt to preserve some of the few remaining pieces of calligraphy by Tsang Tsou-choi illustrates Lee's point rather well. While he lived, Tsang would fill up every bit of clean surface he could lay his hands on by writing down his tale of woe, blaming everyone including the Queen of England for his misfortunes. And then he became something of a pop icon whose work inspired aggressive bidding at auctions and calligraphy was copied on tee-shirts. A need was felt to preserve the few remaining examples of his handiwork on Hong Kong's walls. A pillar on the Star Ferry Pier, displaying one of his typical rants, proclaiming himself as "The King of Kowloon", was wrapped in a transparent plastic casing to that end.

Lee agrees putting a protective sheath around street art is indeed jarring. The whole project of trying to preserve, collect or put graffiti in a museum is at odds with its original intention.

"When he created these, Tsang Tsou-choi never meant them to be looked at as art in the first place," says Lee. "People could relate to his anxiety and grievances, expressed in the form of calligraphy. It kind of became an alternative form of art. By turning these into high art and trying to preserve them one would completely ruin the nature of street art."

He doesn't mind the merchandizing of Tsang's calligraphy though, by having them copied on mugs and cushion covers.

"If it's public art, it's public property and people should have access to it to make whatever they please with it," he says.

Older modes don't cut it

Both Lee and the artist Lam seem to agree that while Hong Kong people are beginning to wake up to the presence of public art in their immediate surroundings - a happy development for which the Gormley nudes were perhaps the immediate catalyst - what's probably still lacking is not so much the acceptance of public art as a valid art genre but the imagination to come up with newer artistic modes of expression, befitting a canvas that's vast, intractable and dependent on public participation.

"There is always a strong focus on the aesthetic side in Hong Kong," says Lee. "That's not the only thing art is about, in my opinion."

Lam says there are just too many similar projects being passed off as public art, at the moment. A way of working round such a lacuna might be in involving "people from all sorts of backgrounds and institutions, bringing different kinds of sensibilities and life experiences" to the table, he suggests.

After all, public art cannot only be about artists. It was never meant to be.

Contact the writer at

basu@chinadailyhk.com

|

Putting Tsang Tsou-choi's calligraphy at the Star Ferry Pier inside a protective cover is at odds with the nature of public art. |

(HK Edition 12/08/2016 page6)