Surviving on a fighting spirit

Updated: 2016-11-22 08:27

By Sylvia Chang(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

HK's population of Nepalese exceeds 30,000. It's been a tough transition for descendants of old Gurkhas soldiers, once considered among Britain's finest. Sylvia Chang writes.

The Gurkhas came to Hong Kong, as proud bearers of a British military tradition esteemed for their fighting spirit, bravery and loyalty. They were the vanguard of an estimated 30,000 Nepalese who live in Hong Kong today. Many now struggle to adapt to a language and culture far different from their Nepalese homeland.

Prem Bahadur Gurung makes Hong Kong his home. He came here as a member of a Gurkha regiment in 1954 and remained until he retired from the British army nine years later, in 1963. He had been a proud soldier. He set out from his hilly village in the Parbat district of western Nepal at the age of 22. Like many young Nepalese he was following a dream of joining the military, then one day returning home with honors and riches. He walked all the way to Kolkata in eastern India, the nearest port to the outside world. It took him 18 days.

Hundreds of Nepalese Gurkha soldiers were recruited by the British army. Gurung, Rai, Magar and Limbu are ethnic groups with large contingents of Gurkhas soldiers.

The Chinese mainland was going through social upheaval in the 1950s. Thousands of people fled across the border and made it to Hong Kong. The Gurkhas' job was to watch the border points and keep things peaceful in Hong Kong.

Gurung arrived in Hong Kong after serving seven years in Malaysia. He was detailed to Fan Ling, across the border from Shenzhen. Climbing up a hill near the border and hiding in the shrubs, Gurung, in army fatigues watched through a telescope for people trying to cross illegally from the other side.

"I saw thousands of Chinese tramping over the mountains and trying to cross the border. The armies on both sides of the border found ways to stop them," 90-year-old Gurung recalled, speaking through a translator. Gurung also monitored the mainland army from a distance. "Whether they were farming or playing football, each move was under my gaze," Gurung said with pride.

He was among the few Nepali soldiers who knew how to read and write, which earned him a place in the communications division, reporting to the commander, by wireless speaker, what he saw across the border.

When he retired from the military and returned to his hometown in 1963, he experienced a glorious feeling of homecoming. The flight from Hong Kong to India took 10 hours. Then he walked for 12 days to cover the distance from India to the place where he was born.

It would be more than 30 years before the Gurkhas in Hong Kong finally stood down, when Hong Kong reunified to the motherland. Most Nepalese Gurkhas and their descendants went to the United Kingdom, promised policy benefits in recognition of their service. Some returned to Nepal. Others remained in Hong Kong.

By then, Gurung had grown old. Life in rural Nepal had been peaceful and would have been idyllic but for the supreme poverty everywhere. The country erupted in civil war in 1996. Innocent people were massacred. Many young people fled the country, looking for a safer, more prosperous future. Some had roots they could trace back to Hong Kong.

Generation next

Gurung's son Arjun Gurung was one. He had married a woman of Gurkha ancestry, born in Hong Kong. He arrived in Hong Kong in 2002. Members of Gurkha families were in demand as body guards, still are and Arjun signed on.

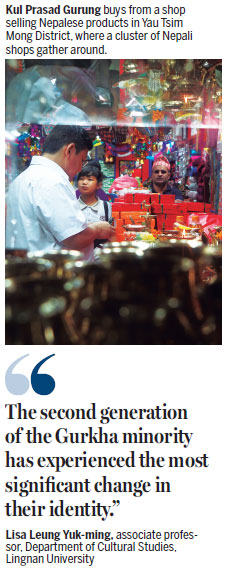

Arjun's friend Kul Prasad Gurung, another member of the Gurkha line, made his exit from Nepal and settled in Hong Kong, accompanied by his Hong Kong-born Nepalese wife. He had been in politics back home but had concluded he foresaw "a very dark future in the politics of Nepal".

"The second generation of the Gurkha minority has experienced the most significant change in their identity," said Lisa Leung Yuk-ming, associate professor in the Department of Cultural Studies in Lingnan University. Leung, who co-authored a book, Understanding South Asian minorities in Hong Kong, said this younger generation continues to struggle looking for a sense of belonging as an ethnic minority in Hong Kong.

"Many of them (second generation Gurkhas) are well-educated, holding degrees in medicine, education and other professions. Given that Nepalese degrees were not recognized in Hong Kong back then, most couldn't continue their original careers," Leung said.

Nepalese who are physically strong and carry the spirit of the Gurkha fighters readily found employment as top-level security guards in Hong Kong. Many others ended up as construction workers or traders engaging in small businesses. Arjun Gurung migrated to that group. He owns a small grocery shop in Yau Ma Tei specializing in products from Nepal and India.

In the population census report on ethnic minorities, released in December 2011 by the Census and Statistics Department, 42.3 percent of Nepalese working population in Hong Kong were doing rudimentary work, involving simple, routine tasks, mainly requiring the use of hand-held tools or physical effort. That included waitresses and construction workers. Over 37 percent were clerical support staff and service and sales workers.

Like their fathers, members of the second generation descendants of Gurkha soldiers retain great affection for their homeland. Most maintain close relationships with friends and relatives in Nepal, and they buy properties in their hometowns. The majority hopes that one day, they will be able to return home, and like the old Gurkha soldiers, will bring back a healthy financial fortune and social recognition.

Arjun Gurung couldn't hide his feelings of nostalgia while he was introducing the village where he was born. Holding a faded color photo of his hometown, he said, "you can live a very slow, simple and peaceful life here".

Kul Prasad Gurung still takes pride in his political ties in Nepal. He said his hometown Pokhara, the second largest city in Nepal, "is just a Heaven".

The two middle-aged Gurkha descendants have served different Nepali associations and organizations in Hong Kong fighting for the rights and social welfare of the Nepalese community. In 2011, Kul Prasad Gurung was honored as a recipient of the Chief Executive's commendation for community service.

The dodgy side

It's never been easy to make a living in a busy, metropolitan city like Hong Kong, where no standard working hours are fixed. It's especially true for ethnic minorities whose rights have not been well-recognized. With the desire to earn money and the pressure to educate their children, the second generation of Gurkhas usually work shifts over 10 hours a day, six days a week.

Unlike most Hong Kong parents who prefer hiring domestic helpers to take care of their children, Nepali families usually send their children back to Nepal where their grandparents look after them. Many others simply keep their kids in Hong Kong, leaving them unattended while they go to work. This, in some degree, opens the door to delinquency. The delinquency problem came into the spotlight in early October, when the police fired warning shots to break up a gang fight in Yau Ma Tei which ended with two Nepalese young men wounded.

In a recent commentary published in China Daily, Nigel Collett analyzed the issue of "a lost generation" in Hong Kong's Nepalese community. A generation, as he defines, "was either schooled to an inadequate standard in Hong Kong, or was sent back to Nepal to study". Collett was a former officer in the British army for 20 years and now works in the security industry for the recruitment of Nepalese in Hong Kong.

He said although the civil strife in Nepal has ended, "the crime, intimidation, violence and loss of trust that occurred then have not gone away." The youth are raised under circumstances which makes it much easier for them to drop out and join gangs within the community, abuse drugs or get involved in illegal trading.

Compared to other ethnic minorities in Hong Kong, the Nepalese community has the highest rate of drug abusers. According to figures released by the Central Registry of Drug Abuse (CRDA), under the Security Bureau in Hong Kong, Nepalese drug abusers accounted for 3.2 percent of the reported drug abusers in Hong Kong in 2015, almost twice the percentage in 2008, when Nepalese accounted for only 1.8 percent of the local population of drug abusers.

The number of drug abusers in the communities of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan altogether accounted for 2 percent of cases reported to the CRDA in 2015 and 0.6 percent in 2008.

Kul Prasad Gurung said the mind of Nepalese parents is changing, albeit slowly. "Many have begun to buy apartments in Hong Kong with a thought that they are going to live here forever," either for their next generation or with a sense that they have finally begun to call Hong Kong home.

Prem Gurung returned to Hong Kong in 2009. His grandson's family bought a flat here and decided to settle down. Prem Gurung said he wanted to be with his family, especially to be close to his grandson. After an absence of nearly 40 years, he came back and now considers Hong Kong his "second home".

While two older Gurkhas were reflecting upon their experience in Hong Kong, 11-year-old Sanjoy Gurung, the third generation of the Gurkha family, was watching a Western cartoon on his smartphone. Occasionally little Gurung spoke up to correct his father's English pronunciation, without raising his head from the cartoon.

He said he had to take extra Chinese classes at school, though he found it "extremely hard". All his friends, most from Nepalese and Pakistani background, like living in Hong Kong, "but just one thing they hate. Chinese (referring to the languages, Mandarin and Cantonese), of course."

When he was asked if he would like to go back to Nepal, he answered, "No. Hong Kong is fun." He blurted out, his head swaying like a rattle drum.

Contact the writer at

sylvia@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 11/22/2016 page8)