Music for deaf ears, a vision for blind eyes

Updated: 2016-04-13 07:59

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Ming Yeung meets three physically challenged people who can do more with their working through disability than most of us.

Disabilities and other nasty setbacks, dealt out by fate's cynical sleight of hand, make us all want to shout, "there is no justice!"

Yet not everybody gets crushed under the wheel. Lots of people can do more with their working through disability than most of us.

Stephen Hawking, the world renowned physicist, crippled by Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, has the best advice for living with disability, "concentrate on things your disability doesn't prevent you doing well, and don't regret the things it interferes with. Don't be disabled in spirit as well as physically."

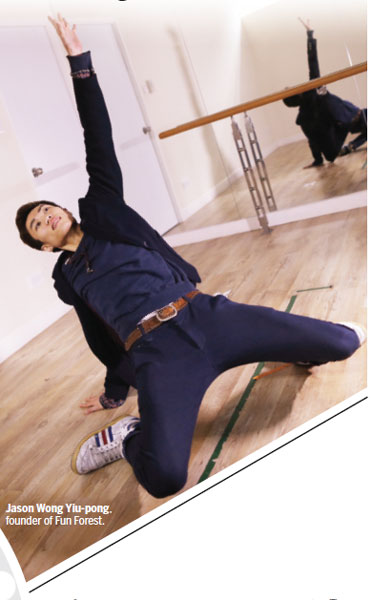

Take Jason Wong Yiu-pong, "dancing the light fantastic", on the floor at Good Lab. He flashes some hip-hop hooks, breaks some moves, with the liquid grace of a professional dancer. That's what he is. He's not even moving to music. There is none. He's deaf but when the music plays, he tingles everywhere, even in his bones and makes music in his heart. He's got every move carefully timed and choreographed. Hip hop is his favorite - he can get right into the vibrations of the rocking bass lines. He still has to learn the lyrics because that's what gives him the interpretation.

His hearing difficulties were diagnosed when he was 6. He wanted to dance early on, but when he got to secondary school, only the girls could take dance classes. All Wong could do was watch them practice after class, but he was enthralled by the moves. He didn't get the chance to try on his own until he enrolled in a short course at the City Contemporary Dance Company. Even then, he didn't get much from it. He couldn't hear what the teacher was saying.

His breakthrough came at a community center offering a course for hearing impaired people. "Fortunately, the instructor knew sign language and dancing. She taught at a slow pace and counted out the beats - completely different from hearing teachers," Wong tells China Daily, through an interpreter.

He did well enough that his teacher encouraged him to join a citywide competition. He took second. Winning helped him get into formal training but it was back to the old problem of not being able to hear what the instructors were saying.

"I lagged behind non-deaf classmates. So I applied again for the course. Bit by bit, slowly, I improved. I stayed after class to clarify points with the teacher. Eventually, the teacher paid more attention to me to help pinpoint my mistakes," Wong recalls.

Wong finally set up his own dance troupe, Fun Forest, in 2010, along with two other hearing impaired dancers. The trio has had plenty of opportunity and productive collaborations with vocalist from Hong Kong and elsewhere.

Dialogue in the Dark HK Foundation sponsored Wong to study at the prestigious Broadway Dance Center in New York in 2014. He became the center's first deaf student. He was disappointed over all. He had no sign interpreter and the school seemed indifferent to his difficulties.

"I felt so bad. I was wondering if I should quit and give up," says Wong, who finally was given an interpreter, following the intercession of a human rights attorney.

Wong still is grateful to his instructors. One asked the whole class to try to dance in a soundless environment so that the hearing could empathize with Wong's difficulty. "I want to inspire others not to give up. There is always hope if you persist. Everyone needs to fight for one's rights and be able to shine," he says.

Most people don't realize that their words and tone of voice are not the most important factors when we communicate with others; non-verbal factors, like facial expression, hand gestures and body language in general, account for anywhere from 55 to 65 percent of how we affect others.

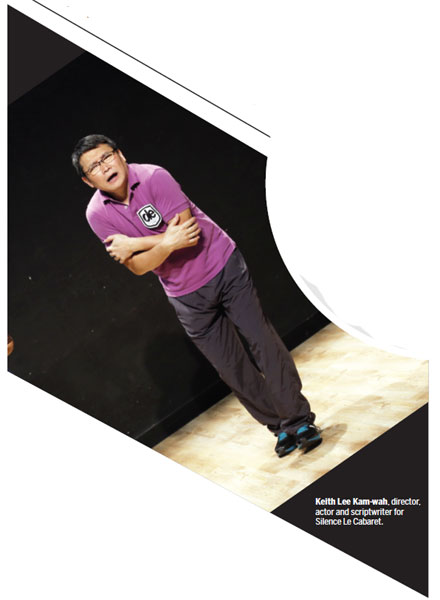

This is what Keith Lee Kam-wah is into. He's director, actor and scriptwriter for Silence Le Cabaret, a performing group that relies on body language to communicate to the audience.

Performing at Good Lab, a group of secondary school students pays rapt attention as the actors relate a story solely by actions and facial expressions.

The students get the idea. They've covered their ears with headsets. What remains of a performance if there is no sound? 'Everything,' answers Lee.

He also believe that the audience learns empathy with deaf people while, at the same time, encouraging those with normal hearing to be more courageous and walk out of their comfort zone to express themselves. If deaf people can communicate in a soundless environment, what's stopping others from learning better communication skills?

Lee lost his hearing after a bout of fever when he was 3. He didn't even realize it until he was knocked down by a man toting a trolley at a wet market. The man had tried to warn him. Lee didn't hear the warning. He got scared, felt alienated and neglected from the outside world. Throughout early childhood and adolescence, he crawled into the shell of a shy introvert.

Lee got into acting after attending an event at a community center. He met a deaf teacher who was strict but who had faith in him, and who gave him inspiration.

In 1986, Lee did his first public show. It was a time when discrimination against non-hearing people was commonplace. There was a time when he tried to enlist a passerby to help him to make an urgent phone call. Nobody was willing to help. 'I was sad and I had to turn to the police for assistance,' he says.

Even training opportunities for deaf performers are limited, he says, because entrance to the Academy for Performing Arts requires five passes a public exam. 'That rules out most deaf people, who study in specialized schools and learn specialized skills.'

Lee then found courses in mime and artistic performance. With his own success, he now hopes to inspire and help other people with hearing impairments to achieve what had previously been unimaginable for them.

While school kids excitedly check out key rings, bags and other designs showcased in the Dialogue in the Dark (DiD) experiential exhibition, Alex Chan Chi-kong, its designer, sits quietly on a bench, steadily holding his cane.

Chan, 43, is almost blind. He has retinitis pigmentosa, a disease that causes progressive degeneration of the rod photoreceptor cells of the retina. The diagnosis fell on him back in 2000. He felt his life snatched away.

'All the things - family, career, love - disappeared bit by bit over the period the disease became more serious,' Chan says. His eyesight declined in progress from decreased night vision in 2003 to only being able to feel blinking or shimmering lights within the next five years.

He lost his job and started learning Braille and other basic skills. 'I could not help but wonder was it enough for an adult? I had no self-esteem.' Through all the trials, he discovered things he had never imagined. He went to work for DiD in 2009. 'This place is a platform for dreaming big,' he said. It was on a flight to Milan for an international conference, Chan proposed to his DiD colleagues, designing something to promote culture of the blind.

'I told them I would like to design a folder in black, with a Braille comparison table at the back. The eight-letter Braille word 'dialogue' would be on the left. Together with the portable Braille device we produced, people could learn the word,' he recalls.

Despite the grand idea, questions remained. How would the folder be produced? How could the idea be communicated to sighted partners?

From design to end product, Chan says the difficulties he has faced are as many as those met by sighted designers, if not more. 'We have to touch the material for a longer time, we spend more time thinking about the color we want for a product,' he explains.

When designing the folder, Chan cut stripes of paper and placed them on the folder to get the feeling if he really wanted it that way.

From plastic folder to T-shirts, slippers, tote bags, key rings, and so on, Chan ceaselessly incorporates items familiar to the blind such as tactile guide paths into his designs. He says his motivation comes from the daily lives of the people who send him feedback.

Through his designs, Chan helps to educate sighted people about the problems faced by blind people, to help them understand that they are not defined by how much they can or can't see. And most importantly, be able to see others by heart.

'Eyesight can't see a person's ability, nor can it see a person's personality. It can only see a person's appearance, hairstyle and stuff,' Chan says.

(HK Edition 04/13/2016 page8)