Time to clear the air

Updated: 2015-11-17 07:49

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

Living in subdivided flats could shorten one's life span, given how vulnerable these are to air pollution. A report by Ming Yeung.

Szeto Kuen, 75, avoids being at home, especially in summer, when the walls seem to close in on his 110-square-feet room, making his throat burn and breathing difficult. He sees a doctor about twice a month. He reckons he's living in bad air.

The air in Szeto's tiny cubicle is so bad that it'll probably shorten his life by a few years. Many living in the city's subdivided units will suffer the same fate.

The presence of small particulate matter in Szeto's home, recorded at over 70 micrograms, averaged over 24 hours, is almost three times higher than World Health Organization's recommended maximum of 25 micrograms per cubic meter. These are PM2.5 particles, so small that thousands could fit inside a dot on a printed page. They penetrate the respiratory system, leading to a Pandora's Box of ailments, and potentially, early death.

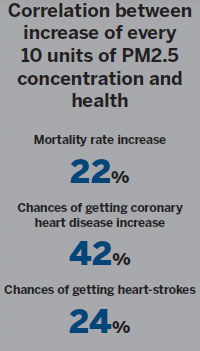

According to the most recent study by the University of Hong Kong (HKU), every 10 units of PM2.5 concentration accelerates mortality rate by 22 percent; chances of getting a coronary heart disease increase by 42 percent and heart-stroke by 24 percent. More than 60,000 elderly people were surveyed between 1998 and 2011 to arrive at the figures.

The Clean Air Network joined Concerning CSSA and the Low Income Alliance to study PM2.5 concentrations in 44 subdivided units in Sham Shui Po, Prince Edward, Mong Kok, Kwai Tsing, Tai Kok Tsui and To Kwa Wan, from mid-June to mid-August 2015.

The 24-hour average of microscopic PM2.5 concentrations in the 44 units was 27.8 micrograms per cubic meter, much higher than the 16.1 micrograms per cubic meter recorded at nearby air quality monitoring stations (AQMS) on the same day. Somewhere between the monitoring stations and people's homes, pollution levels were seriously jacked up.

Scrapping old buses

The Environmental Protection Department (EPD) started monitoring PM2.5 concentration in 1999. Monitoring stations were set up at Tap Mun, Tung Chung, Tsuen Wan and Central. Since March 8, 2012, EPD has been providing real-time data of PM2.5 from all air quality monitoring stations.

PM2.5 emissions come from burning waste, restaurant kitchens and especially internal combustion engines of cars, trucks, buses and ships. Over half the pollution we inhale is locally produced, especially on the roads and in the harbor.

"Major sources of suspended particulates in our environment include power stations, marine vessels, construction work and vehicle exhaust," according to the report Air Quality in Hong Kong 2013, released by EPD's Air Science Group.

To reduce roadside pollution, EPD's policy is to replace older, dirtier franchised buses with Euro 5 or 6 models. The cleaner buses started in operation last year and the fleet is expected to grow substantially by the end of 2016.

To shift to greener technologies, including electric buses and hybrid buses (buses equipped with batteries, in addition to their fossil fuel engines), the government also provided a one-time grant for 18,000 diesel taxis and 6,000 public light buses to convert to liquefied petroleum gas. EPD notes that from 1999 to 2013 roadside PM2.5 levels in Hong Kong dropped by 37 percent.

Even though roadside air quality has been improved, the heat from the cluster of restaurants and shops on the street, three floors below his flat, still bugs Szeto. "The shops below that sell roast meats make the air so bad that I can barely open the windows," Szeto says, pointing to the thick dust around the window frames.

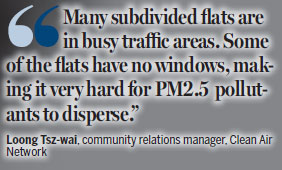

"Many subdivided flats are in busy traffic areas. Some are near ships' berthing areas, like Kwai Tsing," said Loong Tsz-wai, community relations manager of the Clean Air Network. "Some flats have no windows, making it hard for PM2.5 pollutants to disperse."

Windowless homes

The Buildings Department would consider windowless subdivided units a serious irregularity of building works.

In Szeto's case, vehicles start in early morning, dumping exhaust fumes until late night. The ceaseless clamor of trucks and cars keeps him awake until midnight. Then it starts again at 5-ish.

He tries to spend as much time as he can at the nearby air-conditioned Dragon Centre. But the mall, to keep the traffic moving and discourage loiterers, installed narrow, sloped benches - not very comfortable for anyone who wants to sit a while.

Szeto's children pay the HK$3,000 monthly rent for him. He hates being a burden, so to save on the electricity charges, he keeps the air-conditioner turned off until night.

Szeto has applied for public housing. He wants to stay in Sham Shui Po, where he's lived since 1962, but he wants to live in a place that feels like home.

Half of the respondents to the Clean Air Network survey thought the air quality in their homes was seriously poor. Ten percent reported family members having coughs, allergic rhinitis, airway allergies, and other afflictions, said Loong.

Loong added that the "street canyon effect", when high-rises are built on adjacent blocks, obstructs ventilation, trapping pollutants in the old, low-rise tenement buildings.

Associate Professor Lai Ka-man of the biology department at Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) said bacteria, ranging in size from 1 to 10 microns, could be part of the problem.

"Knowing that PM2.5 levels in subdivided flats are much higher than normal is only the beginning. We ought to know where these PM2.5 particles come from," Lai commented.

In a study by HKBU and the World Green Organisation, Lai and her team looked at indoor air quality and environmental hygiene in 41 subdivided units in different districts between July and September 2013. Meanwhile bacteria, fungi, and air and dust samples collected from 20 randomly-selected households in Tsuen Wan, Mong Kok, Kwun Tong and Kwai Chung, were tested against the Hong Kong Air Quality Index standard of no more than 1,000 colony forming units (CFU). The bacterial counts ranged from 133 to 6,535 CFU per cubic meter.

Indoor carbon dioxide concentrations and bacterial counts are important indicators of the indoor environment. The study found increased indoor carbon dioxide concentration notched up the indoor bacterial endotoxin count.

Fungal colony

Tenants living in subdivided flats usually don't know bacteria and fungi cause ill health, Lai concedes. "Most complain about unpleasant odors, especially garbage in the back alley. They see rodents and cockroaches everywhere. There is a discrepancy between the reality and what they perceive," Lai adds.

The report concludes overcrowded living environments leading to inadequate ventilation may be the cause of poor air quality. In the units surveyed, space per person was about 41 square feet, 30 percent below Housing Authority's recommended minimum of 59 square feet.

Poor building conditions such as water seepage and poor sewage foster microbial contamination, releasing bacterial toxins.

"If a tenant feels itchy every time he comes home and we find that his pillow has high fungal colonies, then that is the cause of his itching," Lai explains, adding that fungi can be killed simply by washing a pillow cover in water at a temperature above 60 C. Tenants are advised to dry their laundry outdoors as moisture accumulation would induce the increase in bacterial count.

Lai says many tenants pay attention only to tidiness inside their homes but overlook conditions in the immediate area. She believes landlords should take responsibility for providing tenants a healthy environment, by keeping building walls clean, preventing water seepage and subsequent microbial growth.

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

The presence of PM2.5 in Szeto Kuen's home is almost three times higher than WHO's recommended maximum level. parker zheng /China Daily |

(HK Edition 11/17/2015 page10)