Where the dead come home

Updated: 2015-10-27 08:44

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Tung Wah Coffin Home in Sandy Bay was meant to be a transit point for Chinese who died abroad. For some of them, however, the wait to be buried in their native soil has stretched over decades. Ming Yeung writes.

On a hill above Sandy Bay stands a piece of Hong Kong history. It's a century-old monument to the hundreds of thousands of Chinese who traveled afar to seek their fortunes and those back home who cared for them. The old building is also a treasure trove of stories recounting the history of the Chinese diaspora. The Tung Wah Coffin Home is where those who died on their long journey came home.

A pair of couplets engraved on the marble pillars of the reception hall reveals the historic mission: "This is a place for the deceased to repose for a while until they can return to the place where they wish to be buried - their hometown. It is both a tradition and virtue to handle the end of life with due respect," (literal translation).

The facility, sprawling over 6,050 square meters, comprises several buildings - 91 rooms, two halls, a gateway, a pagoda and a garden. The records of a remarkable history of the Chinese diaspora that began around 1850 and continued until the early 20th century are kept here.

The remains of more than 100,000 people have passed through the gateway, returning home from all over the world. They were ordinary people who made their way west, to Europe, and east, across the Pacific, where they built the railroads across North America, searched for the legendary "Golden Mountain" of the Gold Rush Era, or set up shops. The vast migration began at the start of the long era of traumatic political upheaval in China: the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), Boxer Rebellions (1899-1901) and the Xinhai Revolution (1911). The seemingly unending turmoil put many to flight, in search of greener pastures.

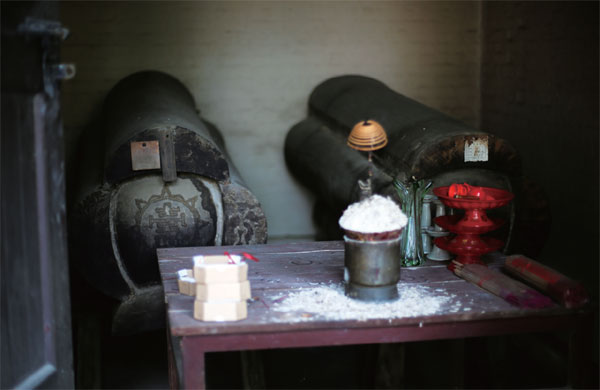

About 120 coffins and bone containers, made of wood, metal or bamboo, are stored in the facility at Sandy Bay. The bodies have lain there for decades, waiting to be claimed by a family member and taken to be buried in their native soil. The color of the traditional brown wood of the coffins has faded over time. They lie, elevated above the floor to protect them from the damp, shielded from the sunlight by red window blinds. The blue and white nylon sheets covering them have accumulated layers of dust. Incense burns in front of each. Caretakers attend to them every day.

The oldest coffin belongs to Tang Kam-chi, one of the founders of the institution who died in 1906. Beside him lies the coffin of his wife, who died nine years later. Floral engravings and the Chinese character "longevity" carved on Tang's coffin are clearly visible, exemplifying the expert craftsmanship of the era.

A repository of stories

The Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGH) built the coffin home as a labor of charity, to oversee the transportation of "fallen leaves returning to their roots". The place facilitated the "reunion" of those who died abroad with their grieving families in China. That undertaking often lasted more than a year and required the assistance of the gigantic worldwide network built by the hospital's 13 founding directors whose trading interests spanned the globe.

TWGH arranged funerals and served as an information center, reaching urgent messages from overseas associations to their fellows living in China. In the Universal Circulating Herald in 1880, there was a notice, warning mainland Chinese to stay away from Melbourne, Australia, cautioning them against the unconscionable exploitation of Chinese workers by their employers.

Another account, published in the same newspaper in 1881, highlighted widespread hostility toward Chinese laborers arriving in North America. The writer recommended that the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) government provide education and opportunities at home, so that workers would not be forced to go abroad.

By 1960 the home contained 670 coffins, 8,060 exhumed remains, as well as the ashes of 116 who had been cremated. The coffins were stacked to the ceiling, says Sunny Ng, caretaker at the home.

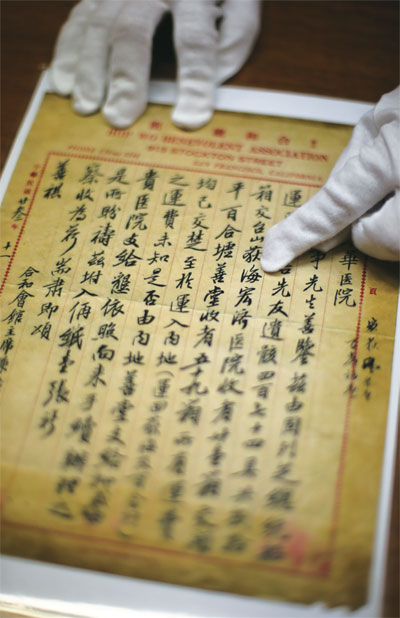

TWGH meticulously recorded the details of each case they handled, tracking the arrivals and departures of the deceased. Caretakers were watched closely, lest they resort to extorting money from bereaved families.

The records had been filed away and forgotten, until an archive of the 1949 Portland bone shipment list was re-discovered in 2003, by Stella See, head of TWGH's Records and Heritage Office, and her team. The records, wrapped in tissue, had been stored in a cabinet in the office library, after being moved out of the coffin home in 1970.

Scattered in front of See, thick black folders inscribed with yellowing characters, record the details of coffins received, then later dispatched to their final resting places. She points to insurance documents, bills of lading, lists of the dead and their hometowns. For some of them, there are detailed handwritten notes on how the end came.

A short and slender Chinese man, wearing a hat, looks vacantly into the camera lens in an old black and white photo. Pile upon pile of sugarcane is stacked behind him. His ankles are in chains.

He was an indentured coolie at a sugar cane plantation in Peru, See explains. There are reports of certain Chinese throwing themselves into boiling cauldrons of sugarcane juice, to escape the tortuous working conditions.

"The earliest record we have is dated 1929, but we believe, from other evidence, the bone repatriation service started way before that," See says. As early as 1874, a shipment of bones was sent from Japan to Tung Wah's old coffin home in Sheung Wan. "Without these records, no one would know that such a history exists."

See and her colleagues contacted Chinese associations in the United States looking for information to augment the history but none was found. "For the time being, there is no record from the shipping country or the Chinese mainland." This is not entirely surprising, because Chinese, as always, are reticent and evasive when it comes to dealing with death.

The search for more information, See concedes, required piecing together the broken history, to discover the intriguing truth of what appeared merely routine at the time.

A letter delivered to TWGH in 1933 from a law firm in Los Angeles, California, indicated that the group handled the funeral of Wong Ah-you, who died on board the President Coolidge, a ship owned by the Dollar Line, two days before Wong was scheduled to arrive in Hong Kong. Wong's father wanted to show gratitude by defraying the funeral expenses.

"However different a life they lived, they shared one common belief: they did not want to become lost souls," See explains. That was why the group kept a "soul collection box" for the dead whose remains could not be located or retrieved.

There were countless cases similar to Wong's. Through sheer misfortune many suffered untimely death, while sharing the common fear of being abandoned in a foreign land or at sea.

"As passengers died on the long voyages from time to time, and knowing how much Chinese feared being buried at sea, the hospital provided coffins on board ocean-going vessels, so that deceased passengers could be returned to China for burial," writes historian Elizabeth Sinn in her book, Pacific Crossing: California Gold, Chinese Migration, and the Making of Hong Kong.

Now in digital format

The heritage office has taken tremendous efforts to digitalize the historical records, many of which are decaying. The daunting task could not have been accomplished without the help of volunteers. A retired barrister helped with translating words written in traditional Chinese character into English.

The digitalized material has been made available online, bit by bit, providing a valuable archive for anyone interested in the history of TWGH.

Some poorly-preserved records, dated 1916, have not been touched at all. The employees fear that the documents, even if gently unfolded, might disintegrate.

See says getting professional help for restoration work - given the volume of resources - is beyond the group's means for now.

The records however are a testament to Hong Kong's role in the repatriation of China's fallen sons and daughters. "Without Hong Kong, such a history would not have existed; without Tung Wah, this philanthropic service would not have been carried out," See stresses. "After all, philanthropy prevailed against all difficulties."

Co-organized by TWGH and the Chinese American Museum, a year-long exhibition - Tales of the Distant Past: The Story of Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora (A tribute from Tung Wah Group of Hospitals of Hong Kong) - opened in Los Angeles this month. It runs till October 2016. The exhibition also commemorates the group's 145th anniversary.

The exhibition comprises more than 100 valuable archived items and artifacts from the collections of Chinese American Museum, the Tung Wah Museum and others.

Organizers hope Chinese-Americans will learn more about their Chinese roots through the exhibition. It's their chance to look back on the difficult early days of the vast Chinese migration to the USA, when their ancestors struggled to earn the means to survive.

Maisy Ho Chiu-ha, chairman of TWGH, noted that the bond between Hong Kong and California goes back to the 19th century, beginning roughly with the Gold Rush.

Eighteen student ambassadors were selected from secondary schools run by TWGH to take part in an educational tour to Los Angeles from Oct 3 to 10. By researching assigned topics, through literature review and visits to local Chinese organizations in Los Angeles, the students were challenged to inquire into the lifestyle and beliefs of Chinese migrants of past and present. Another group of 36 students traveled across the border to Kaiping, Guangdong, where many Chinese set off to fulfill their dreams of seeing the Gold Mountain.

The students will produce short videos on their assigned topics. The projects will be used as teaching materials in TWGH's moral education curriculum.

The idea of having moral education on the school curriculum is to enhance the pupils' sense of national identity, as well as promote the virtues of love and respect. The group's Education Services Secretary, Kenneth Wu Kee-huen, says that the bone repatriation service is an ideal example to represent TWGH's core values.

Consisting of 18 chapters, the curriculum spans primary one to primary six, with supplemental chapters up to secondary three. The aim of this spiral approach, Wu stresses, is to help students grasp complex, abstract concepts informing the history and tradition.

"It is not about history but moral and value education," Wu adds. "History is used as a means to present current social problems and by analyzing the themes students come up with their own answers as to what is right and wrong."

Professor Marlon Hom from Asian American Studies Department at San Francisco State University concludes on the basis of available records that the time-honored bone repatriation service ceased to exist in 1949, due to the three-decade-long international embargo between the newly-established Chinese government and the US, leaving some bone containers stranded and unable to make their homebound journey. Those who were stranded in the coffin home were interred in a mass grave, at the Lo Wu border area.

From the 1960s onward, people who came to Hong Kong from the mainland tended to stay and eventually made the island their home. It was their will to be buried in their adopted home.

Some remains that had come back to the mainland were returned to the US for reburial.

Sunny Ng hopes the public understands the value of the work done by the home and the benefit it continues to provide. "We are only service providers. From the past to the present, we provide service to the dead."

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

Incense burn in front of each coffin and caretakers attend to them every day. |

|

Stella See says getting professional help for restoration work is beyond the group's means for now. |

|

Bone containers, made of wood, metal and bamboo, are still stored in the coffin room. |

|

TWGH meticulously recorded the details of each case they handled, tracking the arrivals and departures of the deceased. |

|

The oldest coffins belong to Tang Kam-chi and his wife. |

|

Tung Wah Coffin Home is a treasure trove of stories recounting the history of Chinese diaspora. Photos by edmond tang / China Daily |

|

The bodies have lain there for decades, waiting to be claimed by a family member. |

3

3