Pop goes the factory lore

Updated: 2015-09-01 09:14

By Chitralekha Basu(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

There is an explosion of material related to the city's industrial past on the Web, as well as in the collectibles market, and Hong Kong seems to love it. A report by Chitralekha Basu.

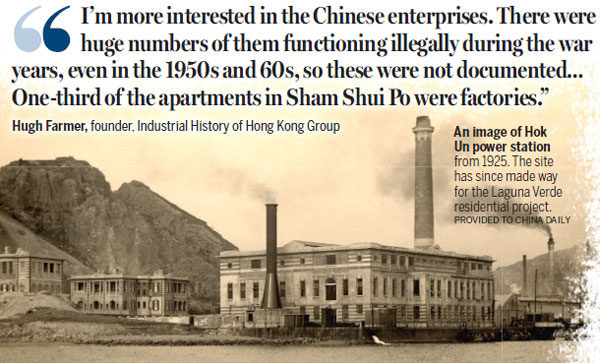

website floated by a long-time HK-resident English gentleman - industrialhistoryhk.org - gets 300 hits a day. People log in to check out quaint images of early 20th century packaging and advertising graphics. They are awe-struck when told salt mining in Hong Kong began in 3rd century BC. Canny readers of the website raise penetrating questions. For example, if the man in a 3-minute film short, shot by Sir Lindsay Ride during the years of Japanese occupation (1941-45) is shown carrying blocks of ice in baskets hung from a shoulder pole, when exactly did the hand-pushed trolleys for carting ice come into use?

Begun only in October 2013, the website has accumulated over 120 writers who post fresh stories at the rate of one a day. There are over 700 posts at the moment.

Hong Kong Heritage Project ("the largest collection of oral history recordings in Hong Kong," according to its director Fanny Iu), began in March 2009. It features 470 plus interviews of industry captains, small entrepreneurs and factory hands. Their archives contain 150 linear meters of industry-related documents, over 8,000 photographs and more than 1,000 maps, including that of factory sites and floor-plan blueprints. The website has totted more than 70,000 hits as of now.

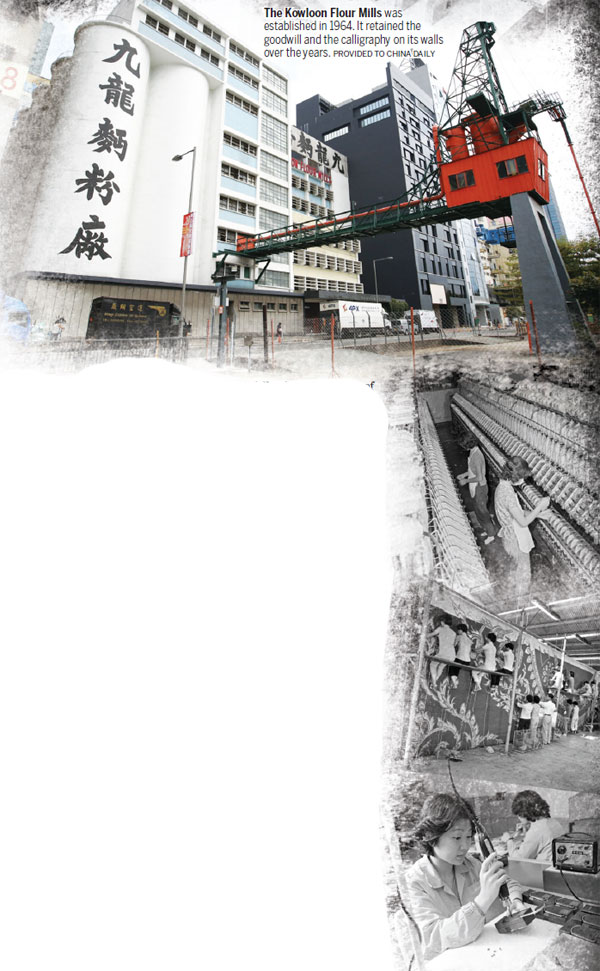

Industrial History of Hong Kong Group (industrialhistoryhk.org) and Hong Kong Heritage Project are just two examples of a likely surge of popular interest in Hong Kong's industrial past. Suddenly, just about anything related to Hong Kong's entrepreneurial achievement is hot property. It's another matter that its glory days ended at least 30 years ago, when entrepreneurs began moving base to the Chinese mainland.

From museums to individuals, everyone seems to want to engage with Hong Kong's industrial past. Hong Kong Museum of History recently launched a campaign to collect industry-related artifacts and memorabilia. Picture This Gallery in Central caters to a new generation of aficionados, ready to snap up industry-related collectibles and antiquities - from calendars featuring cheongsam-clad models endorsing 555 Cotton, to vintage bonds released by the Chinese Imperial Railway to fund the construction of the Canton Kowloon Railway in 1936.

Those who cannot afford to own a piece of history try to absorb the images and factoids from Hong Kong's industrial past by visiting websites, archives and exhibitions. The Factory Hong Kong Exposition, underway at Hong Kong Heritage Discovery Centre until Sept 13, has seen 13,000 footfalls since it opened in July. The models, paintings and installations, put together by students of Hong Kong Design Institute, is an attempt to memorialize "the golden era of Hong Kong industry", which, according to assistant curator Terence T.C. Ng, peaked between "the early post-war period, i.e. mid 1940s to mid-1980s".

Search for identity

There is probably a reason why the appeal of industry-related nostalgia is particularly strong at this moment.

"When there is a crisis and a general discontent, people want to compare the past and the present, they want to examine how people responded to similar events that took place in the past," says Timothy Wong, professor of history at Hong Kong Baptist University. "People are especially reminded of the economy of Hong Kong from the 1950s to the 1980s, when Hong Kong industry flourished, now that, after most industries have shifted base to Chinese mainland, all they are left with is nostalgia."

Stephen Davies, fellow at the Real Estate and Construction Department, University of Hong Kong, adds, "Most of Hong Kong does not seem to have a memory of this place extending further back than the 1980s, except through family photographs, although most people and their forefathers migrated here in the 1950s through 70s. None of the ideological explanations about their Chinese identity offered to the present generation of Hong Kong people seems to resonate with history. So the people are looking for answers. Exhibitions, oral history, objects and artifacts from the past are vehicles of memory, touchstones of identity."

Ghosts of industries past

Hugh Farmer points to the industrial buildings along Wong Chuk Hang Road, across from the Aberdeen Sports Ground, saying they won't be around for long. While Farmer is reconciled to the inevitable erosion of traditional forms of industry, what rankles him - or did for a long time - is the apparent reluctance of Hong Kong people to at least hold on to the memory of their industrial achievement.

"Post-war, Hong Kong was the biggest manufacturer of textiles in the world," says Farmer. "They moved the money, machinery and know-how from Shanghai. In Hong Kong they found the perfect condition, temperate weather, cheap labor, as more refugees settled here, and a non-interfering government. These were some of the first factories with air conditioning. That tradition is simply forgotten."

He was pleasantly surprised to find there were probably more people who cared for that narrative than he had thought, once he started the Industrial History of Hong Kong Group, particularly since the launch of the website, which seems to have assumed a life independent of its creator. Today the portal is a veritable explosion of Technicolor advertisements, facsimiles of old documents, black and white film footage, first-person accounts as well as a platform for debate. "I haven't actually met most of them," says Farmer of his contingent of 100 plus contributors. "People the world over - even those who have lived in Hong Kong for just a year - seem to be interested."

Factory girls

"We were confident enough to reject overtime and Sunday work," says a former female factory worker in one of the videos recorded as part of Hong Kong Heritage Project's Oral History Program. "We would boast about having air-conditioning at work. The 1980s were the boom time - the peak season for manufacturing. I never considered leaving the garment industry."

Such effervescence and buoyant energy seem to be generic to the women featured at the Factory Hong Kong show, basking in the glow of their new-found economic freedom in that era.

"For these women working in a factory was about empowerment, apart from being a chance to build a social network, make decisions, support the family, and rise in stature within it," says Wong.

"Those working in electronics goods manufacturing gave an impression that they were more fun-loving than those working in garment factories, who kept longer working hours," adds Ng, drawing attention to the pleasant, contented faces of women assembling machine components. "Electronics manufacturing units had fixed working hours. The girls had more time on their hands outside of work, to go dancing for instance. Factory hands earned more than a woman doing a white-collar job in an office."

On the flip side

It does not take a cynic to figure everything couldn't have been quite as hunky-dory as it might appear in the recent expositions of Hong Kong's industrial history. As Wong reminds us, "They worked very long hours, the ventilation was poor, there were hygiene issues and there was no maternity leave to avail."

Sometimes the simmering discontent would erupt and explode in the public domain. The 1967 riots that left 51 dead, including two small children killed by bombs planted outside the Kiangsu and Chekiang Primary School, was in fact triggered by Leftist trade union-induced labor unrest in a plastic flower factory in San Po Kong, following the sacking of 300 employees.

Liuda Tours recently started a 1967 riots-themed excursion, led by London School of Economics graduate Zhang Longyi. Tourists looking to stock up on local history are taken to the rooftop of Kiu Kwan Mansion on King's Road, North Point, where Zhang re-tells the story of how helicopters sent by the British administration to quell the uprising were lowered on the roof of the building, and the cops ambushed the Leftist trade unionists who had been running a veritable "hospital" for injured colleagues in the basement.

The tour ends at the giant Montane Mansions, in Quarry Bay, a never-ending beehive of residential units from some of whose matchbox establishments, and tiny 2 square-feet balconies, added as an afterthought, the residents run small enterprises. "There are people who can carry on with their lives, without ever having to leave this building. It's here they live, go to restaurants, work or school," says Zhang. It's a tradition which seems to have endured over the years, tying up Hong Kong's industrial past with the present.

It is the narratives of these small, precariously-existing, some now-extinct businesses that Farmer finds more exciting than that of the obvious big-time corporate houses like HSBC and Swire, who have well-charted-out projects to archive their own history.

"I'm more interested in the Chinese enterprises," he says. "There were huge numbers of them that functioned illegally during the war years, even in the 1950s and 60s, so these were not documented. There were loads of stuff being manufactured in people's homes. One-third of the apartments in Sham Shui Po were factories."

Armchair historians

He is aware of the random, arbitrary nature of the website he runs and that not all posts on it are supported by strong incontrovertible evidence. "People write to correct our errors, they like to engage in that kind of dialogue," he says. Some of the articles are cross-verified meticulously by academics though, like a recent one on the Taikoo sugar factory.

Anything to do with history that's presented on a non-academic register - be it a Web portal, an exposition, a book or a film - will likely be questioned as to its reliability and for any tendency to romanticize hard facts. The explosion of material related to Hong Kong's industrial past in the public domain too may not be an unmixed blessing.

"Memoirs are bound to be romanticized," says Wong. "People tend to attach sentiment to it for that's human nature. Historians need to take a critical approach to the material available."

"Unless the person putting it together is a total masochist, any narrative about Hong Kong, or anywhere else, for that matter, would have positive elements to it," says Davies. But then, he points out, Hong Kong probably lends itself to idealization, given the way it has shown exemplary resilience and true grit against the face of huge odds, time and again.

"In the 1970s, there was an acute shortage of work in Hong Kong, firms were downsizing. The HK work force decided to share work. Everybody took less money to make sure their work mates kept a job and an income. It says something about the collective sense of social identity and working class solidarity, as well as acceptance of that by their employers," says Davies.

He even sees "a shade of Confucian paternalism" in such generosity of spirit.

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 09/01/2015 page11)