The battle for recognition

Updated: 2015-08-27 09:05

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Even as Hong Kong gears up to celebrate the 70th anniversary of liberation from Japanese occupation, some of the relics of the city's terrible trial - which local historians feel are worthy of a world heritage status - lie in utter neglect. Chitralekha Basu reports.

Caked in a thick layer of dark green gunk, the concrete pile is almost merged with the green landscape. At closer look, the structure turns out to be a phalanx of polypropylene sacks, stacked against each other in a tight semi-circle, now covered with slime and a layer of rotting leaves. A long-tailed grass lizard slithers by, one of the few signs of life in an otherwise desolate area. The sand inside the bags is frozen solid - stratified under 74 years of apathy.

These are the remains of a blast wall at Station 2 of the Wong Nai Chung Gap Trail. The fortification was built around a platform where two 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns were mounted in what was one of the last outposts of Allied defense before Hong Kong's surrender to the Japanese forces in December 1941. Not far away, atop another knoll, at Station 5, troops of HQ Company, Winnipeg Grenadiers, bravely held out for 12 hours even as they were completely outnumbered by the Japanese garrison. That was until the enemy dropped grenades through the ventilation shaft of pillbox JL01, injuring all defenders. Sergeant-Major John Osborne, who posthumously earned the only Victoria Cross to be awarded in the battle for Hong Kong against Japanese aggression, died in the combat.

The Wong Nai Chung Gap trail is one of the better-maintained sites of World War II-related heritage in Hong Kong. The relics of the resistance to the marauding Japanese army - artillery batteries, ammunition magazines, pill boxes, gun emplacement sites - are marked with signposts. A board outlines the route map at the entrance. Catchments have been cordoned off for easy access.

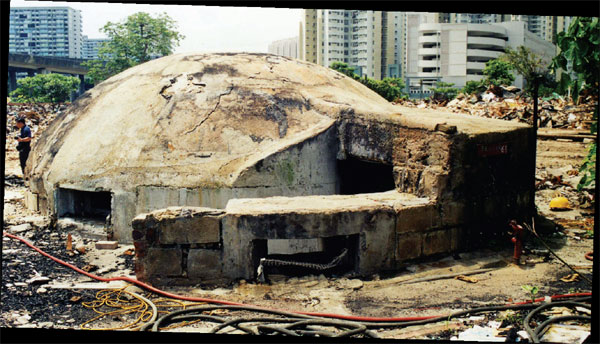

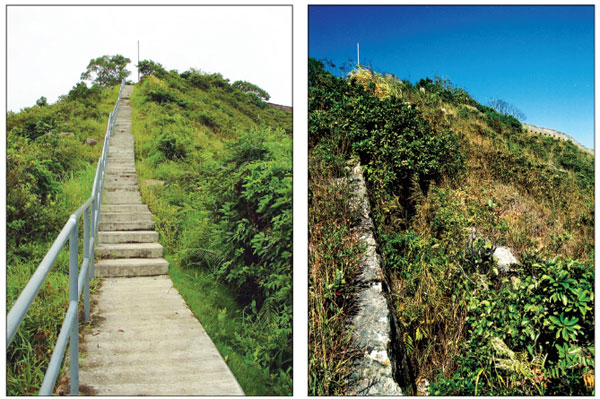

There are, however, numerous other sites in Hong Kong where the remnants of World War II lie un-acknowledged, un-cared-for and exposed to the vagaries of nature. Several of the historic sites have been demolished to make way for development or built over. A staircase was constructed over a trench in Devil's Peak for the benefit of morning strollers. An enormous Japanese pillbox in the old Kai Tak terminal, which became eclipsed by squatters' housing until the area was cleared in 2002, has since been dismantled.

As Hong Kong prepares to celebrate the 70th anniversary of liberation from Japanese occupation, on Sept 3, the remnants of Hong Kong's military history of the period probably deserve a higher reverence.

150 years of colonial history

Hong Kong history expert and historical photographs researcher Ko Tim-kung believes the relics and sites related to the fall of Hong Kong in 1941 are worthy of world heritage status. They encapsulate 150 years of world history, he argues.

"Although today we look at the sites - Shing Mun Redoubt, Devil's Peak, Wong Nai Chung Gap West Brigade HQ and associated bunkers and pillboxes, Mt Davis, Tai Tam Gap East Brigade HQ and associated bunkers and pillboxes and Sai Wan Fort/Battery among others - as those associated with the Japanese invasion of 1941, many of these gun batteries were in fact built in the 19th century," says Ko.

"The Battery Path leading to St John's Church, in fact, was built in the 1840s, as part of the British effort to fortify Hong Kong in the lead-up to the Opium War." Originally, the fortification was meant to keep away the Chinese. In the 1850s, the British planned resistance against other European powers, amid growing colonialist contention that led, finally to World War I.

"By the 1890s, Hong Kong had become the most important entrepot of East and Southeast Asia. A news item from the Hong Kong Telegraph of 1897 raises the alarm over the possibility of a combined fleet of French and Russian forces attacking Hong Kong," Ko observes, stressing the strategic importance of Hong Kong in the context of the British imperialist doctrine.

"So the military structures, or their remnants that we see today - the bunkers, pillboxes, batteries, magazines, ammunition and provisions storerooms, anti-aircraft gun emplacements - are about 150 years of world history," says Ko. "If these sites were granted world heritage status, all the stories in that narrative could be linked, to give visitors the whole picture of European imperialism in Asia."

In pre-1997 Hong Kong, the city's British governors were not keen about memorializing the history in which they were on the losing side. "British-ruled Hong Kong was a colony after all," says Ko. "The battle of 1941 was a watershed moment in British history which the British wanted to play down as far as possible."

Approached by the UK-based After the Battle magazine in 1984 to recommend World War II relics which they wanted to feature in an article, a Hong Kong University professor had supposedly said, "Oh but I don't suppose they exist anymore."

Fortunately, such ignorance has given way to enlightened scholarship. Among the fresh, new breed of experts on the subject is Kwong Chi-man, who teaches history at Hong Kong Baptist University. Kwong, who co-authored Eastern Fortress: A Military History of Hong Kong, 1840-1970 (HKU Press) with Tsoi Yiu-lun, concedes that the significance of historic military structures in Hong Kong is not restricted to the city's history alone, but encompasses "the history of the transformation of military technology from the 19th century to mid-20th century" in general.

"Most of these structures were relevant to the period between 1900 and 1957. The world was constantly at war, East Asia, especially. It was an era that spanned the takeover of the New Territories to the decommissioning of all coastal armaments in Hong Kong. These structures are the testimonies of a colonial power attempting to hold its eastern stronghold during a turbulent age that saw the deaths of millions," he says.

Kwong believes that the battle sites of Hong Kong, where the nameless soldiers died fighting for the colonial government, are similar, in ethos, to the Meiji era industrial sites in Japan, given world heritage status last month. The inclusion of the sites related to Japan's industrial revolution under the Meiji emperor from the 1850s to 1910, on the World Heritage List (WHL) stirred a controversy. Critics have harshly observed that Japan's industrial prosperity of the era was built on the backs of bonded labor press-ganged from Korea and Taiwan.

"In a sense, the relics of Hong Kong's military history are similar to the Japanese industrial heritage and equally important, because they show the other side of industrialization," says Kwong. "In short, both serve as a reminder of the destructiveness of the blind pursuit of a narrowly-defined 'progress'."

World Heritage candidate

Pitching for world heritage status is a lengthy, intricate process. It requires meeting one or more criteria listed in the UNESCO convention for inscription to the WHL. For any candidate from Hong Kong, the nomination is made through the relevant "State Party", i.e. the Chinese government, who puts it on their "Tentative List" submitted to the World Heritage Committee (WHC).

"China currently has 54 properties already on its Tentative List," says Joseph King, director of the Sites Unit under the International Center for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM). The agency serves as an advisory body to WHC. "It is also quite possible that a site on the Tentative List will never make it to the nomination stage."

Only a few world war-related candidates have ascended to the WHL. Among the two notable inclusions are Auschwitz and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. Doubtless, a tough act to follow for any heritage list aspirant, across the categories.

"There are hundreds of battlefields, military structures, and military infrastructure that have been constructed around the world wars and still exist, yet I can't think of any that are on the WHL," says King. Auschwitz and Hiroshima, he says, made the cut as "both are obviously linked to specific events or activities during the war that had a larger impact on the world as a whole".

World Heritage status, King points out, does not necessarily guarantee better conservation of the listed property. "Even if it had world heritage status, the responsibility for the protection and safeguarding of the sites always rests with the 'State Party'. It is not as if UNESCO sends in caretakers to each of over 1,000 properties on the WHL," he says. WHC however, "might ask the State Party to invite a reactive monitoring mission" in case it hears of a conservation-related problem. In other words, looking after a heritage site, whether or not it carries the world heritage tag, is primarily the responsibility of its custodians.

King's suggestion for safeguarding Hong Kong's WWII relics is "to begin an awareness campaign, concerning the existence of this heritage, its importance to Hong Kong and beyond, and its poor state of conservation and presentation". He is hopeful that this might inspire "further research, and also probably would necessitate identifying organizations to support this effort". "I could imagine veterans' groups, historians and historical societies in Hong Kong and others might be interested in such a campaign," he adds.

Private enterprise

Mount Davis Battery, built in the early 20th century, served as the headquarters of Western Line Command. It was exposed to heavy shelling by the Japanese in December 1941. A muddy trail, covered with rotting leaves and twigs, leads to the erstwhile site of five anti-aircraft gun emplacements. Further above are the remnants of a scalloped fortress wall, looking out on Victoria Harbour. The guns once anchored there to ward off attacks on Hong Kong's Central and Western District have long since gone. The area is now used by amateur firearms enthusiasts for target practice. They shoot at plastic bottles hung from trees and ropes strung between the abandoned powder magazines.

"At least you did not see people lighting a fire and posing for wedding photographs around it," says Sinnie Lee, chairperson of Friends of Mount Davis - a group pushing for better conservation of the area since 2005. Lee and Johnny Chan, a co-founder of Friends of Mount Davis, are among the leaders of a campaign to stop the abuse of a heritage site which has gone from being a dumping ground to a favored shooting spot, since it was cleared of construction debris. Evidently, the combination of ruins and wild undergrowth seems to conjure up a romantic appeal, rather than any sense of memento mori for certain people.

About once every three months, Friends of Mount Davis gather a team of volunteers who launch a thorough clean-up. Many of them recently took guided tours of the site and afterward became interested in Hong Kong's military history to the extent that they wanted to care for its relics. The clearing operations, which sometimes involve paid contractors, is partially funded by Hong Kong's Central and Western District Council, though not as a rule.

The group has also drawn up several plans for better maintenance of the site. The fates of a proposed theme park and an exhibition space hang in the balance. However, the campaign to develop a heritage trail linking the existing pathway to the historic structures, have the relics signposted and build a community enterprise for better maintenance of the site, was recently approved by the Central and Western District Council. The HK$ 2.8 million allotted, though substantial, will not cover the costs of building toilets, supplying water and repairing large holes on the trail. Friends of Mount Davis members likely will dig into their own pockets, as they often do, to finance their several awareness campaigns and activities.

Is public-private partnership the way forward to protect Hong Kong's heritage structures?

"We play an important role by making a noise and thereby exerting pressure on the government departments to act," says Lee.

Chan feels even the most sincere government efforts could get waylaid because of lack of expertise and specialist knowledge of the subject. "For instance, after we built a path, the district council became aware of its existence and put it on its official map." Besides, he says, government personnel "are often unable to touch the pulse of the local community, which is where organizations like us can come in".

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com

|

A Japanese war memorial looking out on Magazine Gap Road (left) which was demolished in 1946 and apartment blocks built on it (right). (Images illustrating Ko Tim-Keung's 1984 article in After the Battle magazine.) |

|

The cautionary signpost in Mt Davis is an area (not in the picture) where amateur shooting enthusiasts hang plastic bottles for target practice. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

Japanese troops at Braemar Hill, North Point, launch an offensive on urban areas of Hong Kong Island in an image from 1941. |

|

Mt Davis artillery battery, spanning across 3.3 km, was constructed in 1912 to guard the harbor entrance on the western side of Hong Kong Island. |

|

A Japanese pillbox built to guard Kai Tak Aerodrome during the war has since been removed ostensibly to be re-erected somewhere else. Photo by Ko Tim-keung |

|

A buckeye tree sprouts from the site where an anti-aircraft gun was lodged at Mt Davis in the 1930s. They were later moved to Stanley to strengthen the defense on the southern side of the island. |

|

A staircase was built (left) in 2004 over a trench (right) used by soldiers during World War II for the benefit of morning walkers. Photo by Ko Tim-keung |

|

An intense and unchecked growth of vegetation has nearly obliterated some of the military quarters and ammunition storage units at Sai Wan battery from view. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

A pillbox near Windy Gap photographed in July 1997. It was demolished in December 1997. Photo by Ko Tim-keung |

|

A pillbox in Telegraph Bay before it was demolished in 2001. Photo by Ko Tim-keung |

|

The remains of an anti-aircraft gun emplacement site in Kowloon Bay. Photo by Ko Tim-keung |

(HK Edition 08/27/2015 page7)