Children Of Internment

Updated: 2015-08-13 08:14

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

On the eve of the 70th anniversary of Hong Kong's liberation from Japanese occupation, Dennis Clarke and George Cautherley revisited Stanley Internment Camp where their life's journey had begun. Chitralekha Basu was there.

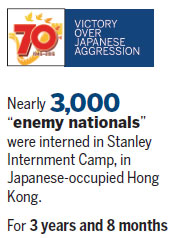

am a child of internment," says George Cautherley. "My mother told me I was conceived in a brothel hotel in the western district of Hong Kong." Cautherley's British parents, Dorothy and George, were among the "enemy nationals" rounded up and brought to a rather sleazy hovel near the present Macau Ferry Terminal, soon after the Japanese seized Hong Kong on Dec 25, 1941.

The detainees were crammed into a cheap hotel with close to 1,000 other people, not knowing how long the ordeal would last and indeed, whether they might survive it. To ease the unrelenting tension on their minds, Cautherley's parents decided to focus on something other than the situation they found themselves in. Having a baby seemed like a good idea.

Cautherley was born on Sept 2, 1942, in Stanley Internment Camp, where he would spend the first three years of his life, roaming around barefoot (shoes were not considered essential supplies) - a bit of a free spirit who did not realize that he and his parents were in a concentration camp with about 2,800 others.

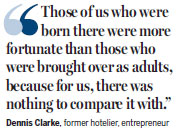

"Those of us who were born there were more fortunate than those who were brought over as adults, because for us, there was nothing to compare it with," says Dennis Clarke. He and Cautherley are the only two people born in Stanley Internment Camp during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong known to be living at this moment. Clarke, born on Jan 31, 1944, was too young to have any memory of life in Stanley. What he does remember has to do with the detritus of war - the sound of the deafening sirens from the battleships moored in the harbor and the searchlights sawing the night sky well after the occupation was officially over.

Clarke and Cautherley, who left Stanley Internment Camp in September 1945 with their families, have lived abroad for many of the eventful years between then and now. They had high-profile careers - Clarke as a hotelier and Cautherley as a leading medical products and biotech industry entrepreneur. Coincidentally, both chose to return to Hong Kong and make the city their home, eventually. Finally, last week, a good 70 years after they had left their camp base at Stanley, Clarke and Cautherley had a chance to catch up with each other - at the very spot from where their life's journey had begun.

Family connections

The grass on a little square patch at the Stanley Cemetery will remain forever young. The tiny enclosure is cordoned off by four headstones, erected in memory of the children who died at the camp. It is located on the way to the spot a little higher up on the slope, where the young soldiers of the Royal Rifles of Canada who fought their last battle to protect the last stand of defense on Hong Kong soil against the advancing Japanese troops are buried.

One of the headstones dedicated to the children was carved in memory of Dennis Clarke's brother Anthony, who died at 11 months on Dec 14, 1942. Clarke would visit the spot with his mother Mildred as a child. It was an annual ritual. "I don't remember those visits being a picture of sadness. It was more like a family outing."

Revisiting Stanley Cemetery in the lead-up to the 70th anniversary of Hong Kong's liberation from Japanese occupation probably inspires a different set of emotions in him today. After all, the burial ground used to be a part of the internment camp area where both he and his brother were born and one of them never left. Clarke, however, sees his personal loss in the context of the big picture. Memorializing war is as much about remembering the dead as well as those who lived to tell the tale, he says. "I didn't suffer in the war, but there were millions who went through hell. For them it was a nightmare. Those scars never healed."

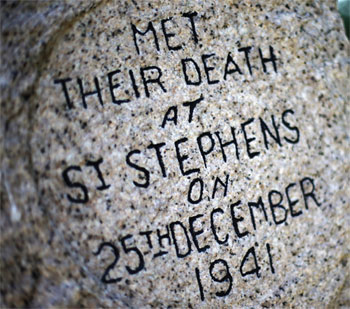

George Cautherley's connection with Stanley Cemetery goes back a century and a half. Bridget, his great, great grandmother on his mother's side, long ago, accompanied her husband, an Irish soldier, Private William Purcell, to Hong Kong. She died in 1864 at a young 26. Not far away from where she lies is an un-hewn granite tablet, engraved with the names of five women. They were the nurses, gang-raped and killed by Japanese soldiers during the massacre of medical professionals and wounded soldiers at the military hospital in St Stephen's College on the morning of Dec 25, 1941. Cautherley's mother Dorothy, a volunteer nurse at the Bowen Road hospital, from where medics were sent on secondment to other facilities, could have been one of them. It was by sheer luck that she was on duty at Bowen Road on that fateful day.

Sharing and caring

Cautherley was born at Tweed Bay Hospital in the camp, as a typhoon raged. His mother was anemic and suffering from malaria when she gave birth. She needed a blood transfusion and special care which the spare facilities at Tweed Bay could barely afford. One of the reasons she pulled through was because fellow inmates pitched in with post-natal care, and helped babysit her infant son.

One of young Cautherley's minders was 19-year-old Mabel Redwood, who would later sometimes push him in a pram around the cemetery. Mabel's older sister Barbara, who married Frank Anslow, a fellow internee, had recorded the birth of "baby Cautherley" in her diaries. Today Anslow is the point person for anyone looking for information on the history of Stanley Internment Camp.

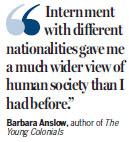

It's a theme she is ever ready to talk about. On the phone from her home in Essex, the spirited 96-year-old reminded us that one of the redeeming features of the internment was the internees' chance to socialize across cultures. This was the first time many British people were meeting fellow expats outside their community - Americans, Dutch and Eurasians . "Internment with different nationalities gave me a much wider view of human society than I had before," Anslow said.

For example, she doesn't remember the Japanese custodians being particularly barbaric, soulless monsters, as they appear in most war narratives. "We didn't see much of Japanese brutality at the camp, only heard about it," says Anslow. "Personally I didn't have any dreadful experiences with the Japanese. I guess it is harder for people who did to forget. After the war we found that our camp wasn't so difficult as many others in the Far East, so we had reason to be grateful for that."

|

Barbara Anslow in a file photo taken in 2008 and (right) with friends on Christmas Day 1941, a few hours before Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese. provided to China Daily |

Clarke would probably agree. He remembers being told by his mother, who was ill during most of her stay at the camp, that she was "very well-treated by one of the Japanese soldiers. The man would smuggle rations for her".

Cautherley too has a heart-warming story about Japanese soldiers, told him by fellow internee Bill Macaulay, who ,then only 12, was drawing a pension from the British Army, for supplying information. One day Cautherley noticed a couple of Japanese officers marching up the slope. Following in their footsteps was a pint-sized humanoid, imitating their gait. Macaulay was terrified of the consequences, in case the soldiers noticed the little mimic. When they did turn around, the officers, far from seeing the act as an insult, seemed greatly amused. Macaulay grabbed the impetuous young Cautherley for it had been he who was having a go at playing army guy and rushed him to his mother before the officers could change their minds.

Taste of freedom

Life was still hard. It was a test of resilience and true grit, pitted against a stack of odds. Soap was scarce. Food contained rat feces. Anslow's diary, which she has since turned into a novel - The Young Colonials - was mostly written on toilet paper.

Yet there were probably only a few occasions when the internees seriously feared for their lives.

"In January 1945, an Allied plane dropped a bomb on the camp and killed 16 internees," recalls Anslow. "This reminded us that if the Allies decided to invade and retake Hong Kong, we would be in the thick of it, and might be killed by our captors."

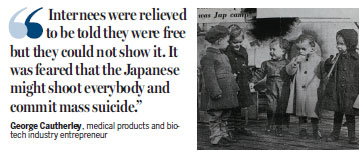

Cautherley has faint memories of his mother clutching him as they watched fellow internees die in that explosion. The other time they were scared was immediately after the announcement on Aug 16, 1945, that the Japanese had surrendered.

"Those two weeks were the most trying," says Cautherley. "The Japanese were still around. Internees were relieved to be told they were free but they could not show it. It was feared that the Japanese might shoot everybody and commit mass suicide."

The tension remained until and even after Rear Admiral Harcourt's fleet arrived on Aug 30, signaling that the war was well and truly over. Freedom remained just a notion until the internees managed to step outside the boundaries for real and walk free.

Postscript

On August 15 this year, Barbara Anslow will attend a VJ Day remembrance event commemorating those who died in the war, at the Cenotaph, Whitehall in London. She will read a poem - The Fepow Prayer by A.E. Ogden and V. Merrett. She is excited, if a little nervous and is hoping it doesn't rain on the day.

Dennis Clarke and George Cautherley will meet again in Hong Kong in December. They will be joined by about 20 others from the world over with links to the Stanley Internment Camp - a mere fraction of a fraction of the numbers who were interned there but good enough to keep the flame of memory burning.

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com

|

Current images of internees' quarters and one from August 1945, showing celebration of the end of World War II (third from left). provided to China Daily |

|

|

|

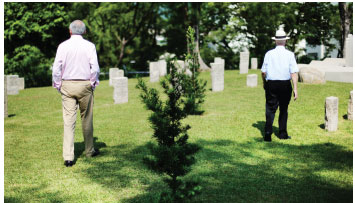

George Cautherley (left) with Dennis Clarke at Stanley Cemetery. (Below, extreme left) Cautherley after landing on British shores with fellow young internees, following their release. |

|

Cautherley (above left) with his parents Dorothy and George during the internment years (right). |

|

Right: A headstone dedicated to the doctors and nurses on duty at St Stephen's College hospital who were brutally murdered by the Japanese soldiers on the morning of Dec 25, 1941 |

|

Above: George Cautherley (left) and Dennis Clarke, the only two people born in Stanley Internment Camp and now living in Hong Kong, revisit the site after 70 years.Photos By Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

Dennis Clarke revisits the grave of his brother Anthony who died during the internment. (Below right) Dennis was photographed with his half-brother Duane Liu 70 years ago at the same spot. |

(HK Edition 08/13/2015 page8)