Help with the Queen's language

Updated: 2015-05-14 07:21

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Even as standards of spoken and written English seem to be on a downward slide in the city, a group of CUHK students are assisting underprivileged kids to pick up the requisite skills. Ming Yeung reports.

Confucius' famous quote "in teaching, there should be no distinction of classes" would sound impractical or untrue in today's highly-stratified societies like Hong Kong.

While the upper strata naturally use their power and influence to make sure their offspring get the best education, higher education opportunities for young people from underprivileged background are shrinking.

A study conducted by the Hong Kong Institute of Education in 2013 revealed that although the number of publicly-funded undergraduate places has increased in the past two decades, education equality has deteriorated with a widening gap between the rich and the poor in receiving university education.

According to the study, the university degree enrolment rate of young people (aged 19 and 20) who come from the top 10 percent of rich families (48.2 percent) is now 3.7 times that of those living in poverty (13 percent), a much wider gap than 20 years ago (1.2 times).

English is the subject students from poorer families probably find the hardest to cope with. Their parents cannot afford the extracurricular classes and tutors to help students make the grades.

Giving back what one learnt

About 40 university students from the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) kick-started the English WeCan project on May 2, to help disadvantaged students learn the language. English WeCan is an intensive four-month English training program offered to some 200 Secondary One students from Band Three schools.

Anakin Mok Man-fai, a Secondary One student from the Church of Christ in China Rotary Secondary School, has been embarrassed by his lack of proficiency in English since he was small. He always felt he was outdone by "smarter students".

"I wanted to learn English but didn't have many chances," Mok complained. He attended an English-medium primary school but was not in an elite class, and felt that more opportunities were given to students with higher grades. He says he is particularly weak in writing, hoping that his writing skills will improve significantly through the English WeCan program.

Lily Wong Hiu-ching said she couldn't comprehend the use of articles in English and found the fill-in-the-blanks exercises a bit of a trial. She also had trouble remembering meanings of words.

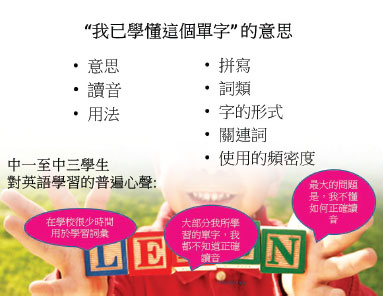

Florence Lam Kam-fong from CUHK's Quality School Improvement Project explains not being able to get the pronunciation right and having a limited vocabulary are the two major stumbling blocks in the way of learning English.

The current theme-based teaching method, a vehicle for teaching a range of skills and content by integrating curriculum areas around a topic, widely adopted in schools, has neglected the weaker students who need to have a clear goal to work towards and be able to achieve it step by step.

Gigi Kwok, a Year Four student in English Language Education at CUHK, said the four-month program makes use of different reading materials through which 500 new words can be taught to students so that they can use them in colloquial and written context.

"There are class activities for tutors to remedy a student's weaknesses in learning English. There is a great flexibility for us to rearrange the learning activities for students, based on their competence," Kwok said.

Kwok feels school education has failed to accommodate the needs of all students, which accounts for the presence of students from different grades in her class.

"By participating in this program, I can apply what I have learned in class to see this new mode of teaching can actually benefit the students, especially the weaker ones," she added.

Every student takes a preliminary test to evaluate his level of competence in English before joining the program. The level-6 test, equivalent to a Primary Three level, is used as a calibrating tool. Competence levels of students vary hugely in terms of getting pronunciations right and reading comprehension capabilities.

An interesting result, Florence Lam observed, was that some students could pronounce the word pretty well without knowing what it was about.

Lam explains the program is based on 20 fiction and non-fiction English books to help students understand the differences between spoken and written English and be able to use them correctly.

"The purpose of the program is to integrate vocabularies and comprehension," Lam said, adding that a student who has completed primary school is supposed to have come across 4,000 English words and understood 1,000-1,200 of them.

"You won't be able to sit for the DSE (Diploma of Secondary Education Examination), without knowing 6,000-7,000 words," Lam said. "Learning 500 words is not simply to help students build a list. Learning the meanings of the words is the key."

Frequent use of the same word, a commonly-used marketing strategy, is being adopted by educators today to help students remember better. From a completely alien concept to being familiarized with a new word, people have to see it 20-23 times, Lam said.

Dreaming in English

Learning a foreign language is never easy, and not only for Band Three school students.

Professor Joseph Sung Jao-yiu, president of CUHK, recalls how his English skills were honed during his PhD study in Calgary, Canada. Sung went to Queen's College, one of Hong Kong's elite boys' schools. And yet his English was poor, the reason why he suffered from a lack of confidence.

"Once you have overcome the embarrassment of making mistakes, you get better and better," Sung said, who realized he had made significant progress when in his dream, he spoke in English, after spending a year in Calgary.

Sung encourages Hong Kong students to be bold and speak English at the risk of making grammatical mistakes. Native English speakers won't mind the mistakes, he contends.

"Imagine a British person speaking in Cantonese to you, although not very fluently. You would be impressed already," he said.

An alumnus of a famous boys' school, Wah Yan College Kowloon, Stephen Ng Tin-hoi, deputy chairman and managing director of the Wharf (Holdings) Limited that funded the English WeCan program, had a hard time assimilating into the English-speaking environment himself.

Fortunately, Ng was egged on by his English teacher who would pick the particularly timid students to go up on stage and speak in front of the class. Ng, being one of the tongue-tied ones, would be asked to perform often. Each time the teacher would pat Ng's back with his strong hands, and command, "Open your mouth! Speak up!"

Concurring with Sung, Ng thinks living in an environment where no other language is in use is an effective way of obtaining a high level of proficiency in a language.

At 19, Ng went to university in Wisconsin in the United States. There was no Chinese in the neighborhood, and during the four and a half years spent there, Ng did not get a chance to visit Hong Kong. The only communication he had with his family was through exchanging letters and recorded cassette tapes.

"When I first arrived there, people asked me why my English carried a heavy British-accent. I didn't want that because I didn't want to be different from them so I deliberately changed to American accent," Ng laughed. "After I came back to Hong Kong, I had to relearn Cantonese as I forgot how to say it."

For students not studying in English-medium schools, Professor Sung said listening to English songs and watching English programs were useful to learn English intonations.

"Gradually, you get to know how to go up or down when speaking a sentence. That way, you can avoid Chinglish as well," Sung advised.

Stephen Ng suggests students should sing out loud the English songs they like. "To cultivate an interest in learning English, music is very effective."

Both Sung and Ng acknowledge that the standard of English is on the decline both at school and workplace in Hong Kong.

Sung thinks one of the reasons could be that young people more accustomed to chatting online don't need to construct proper, grammatically-correct sentences any more. Because of their deteriorating standards, young people are less keen to pick up books and read them through to the end. As they stop reading, the standard goes down even more.

Ng says it's the same for adults. One obvious reason for the decline of English is the growing importance of Putonghua. Even in the business sector and government departments, there are fewer exchanges in English today, Ng observes.

Having tutored two students at Zheng Sheng College, a private school for young people with problems such as drug addiction, Sung says he noted that there was a place for teaching English outside of formal school settings. He met a group of students over breakfast and taught them the difference between scrambled eggs and eggs sunny side up.

He has promised to take the top 10 students in the English WeCan program out to dinner at the end of summer. And they'll be expected to speak English at the table.

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

Joseph Sung Jao-yiu (third from left), president, Chinese University of Hong Kong, and Stephen Ng Tin-hoi (third from right), deputy chairman and managing director of the Wharf (Holdings) Ltd, at the English WeCan kick-off ceremony. Provided to China Daily |

|

Secondary school students and their tutors line up for a group photo on CUHK campus. |

|

The intensive four-month English training program aims to help 200 Secondary One students from Band Three schools improve spoken and written English. Provided to China Daily |

(HK Edition 05/14/2015 page8)