The heartbeat of China

Updated: 2015-04-24 07:33

By Chitralekha Basu in Hong Kong(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

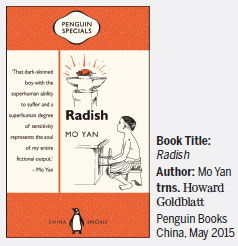

The original Chinese version of Mo Yan's novella Radish, translated in English by Howard Goldblatt and due out in May from Penguin Books, was in fact written in 1984, two years before his cult classic Red Shorghum: a Novel of China was published. Unsurprisingly, Radish anticipates Red Shorghum. The sexual tension between the four major characters in Radish -the mason, the one-eyed young blacksmith, "round-faced" Juzi who is the object of desire between the two men and a pre-pubescent boy, Hei-hai -is relatively understated compared to the unsparing cavalcade of blood-and-gore scenes caused by crimes of passion in Red Shorghum. But Radish is no less disturbing for that reason.

At the center of the narrative is 10-year-old Hei-hai, whose father is missing and stepmother too drunk to care. Hei-hai, who doesn't have a shirt on his back and shows streaks of blood marks around his exposed, knobby knees, must work as an unskilled laborer in a commune in the time of Maoist revolution to claim his bread. His life seems to hang by a thread, ready to snap any moment. Each time Hei-hai smashes his thumb, trying to break pebbles, scalds his arm by pressing it against a red-hot chisel at the blacksmith's workshop, emerges covered with black soot from working the bellows round the clock and is sent out to steal sweet potatoes and radish from a nearby farm, the reader is left quivering with anxiety over how the boy -who is more vulnerable than a fledgling just out of its shell -might hurt himself next and if he would in fact be able to survive it.

Hei-hai's own apparent nonchalance at the disasters that keep happening to him helps exacerbate the trepidation readers feel on his behalf. His outright rejection of friendly overtures by the adults -both motivated and sincere -might be read as a metaphor of a resistance to belong to an individual or to a system. Hei-hai is like a feral child who shuns friends, family, bonding and society. He applies a scoop of dust on his bleeding thumb and goes off on his way, completely unruffled by the suicidal implications of his act.

Mo Yan's masterfully beauteous and richly-textured prose -brought to life in English by Goldblatt's elegant translation -is at its evocative best when he describes nature. Even as human beings claw at each other's throats, cheat, argue and make love, the natural world around them goes on, regardless -magical under the blue-green moonlight, full of mystery and promise in the early morning mist until the rising sun cuts it up "like a knife through bean curd".

Readers have found resonances of the Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez's magic realist style in Mo Yan. In Radish Mo Yan's images are more aligned to the low-key, somewhat nave charm of folk tales than Garcia Marquez's spectacular, in-your-face surrealism. There are a couple of talking ducks though. And the stolen radish left on the still-smouldering anvil acquires an unreal glow, cutting a "golden rainbow arc" across the sky when thrown into the river. None of these images, however, are comparable to the dizzyingly wild and wondrous imagination in Mo Yan's later works such as Big Breasts and Wide Hips, for example, where women grow extra digits next to their thumbs which spiral up like piglets' tails. Radish is a softer, relatively low-pitched version of the unsparingly stark and heartbreakingly-ruthless satirization of Chinese society that will come to define quintessential Mo Yan.

Immediately after his Nobel win in 2012 Mo Yan found himself in the eye of the storm, pilloried for being a writer who, ostensibly, writes "within the system". The writer's response was that one only needed to go to his books to get an idea of his political position. Indeed Radish -his first work of long fiction -cannot leave the reader with any doubts as to whose side the writer is on. For three decades Mo Yan has been writing the story of the human condition -told with unflinching sincerity and preeminent skill. Mo Yan's vote is for the people of China.

basu@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 04/24/2015 page7)