Not as rare as you thought

Updated: 2015-04-01 07:56

By Sylvia Chang(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Misdiagnosis, lack of specialist doctors, hospital protocol - there seems to be too many stumbling blocks in the way of identification and treatment of unusual diseases in HK. Sylvia Chang reports.

Steve Lau knows what it's like to be dead. He's been "there" three times, if that's the right way to put it - a remarkable record for a man of 45. He bears no visible scars and looks like any other man of his age. However, he had cardiac surgery three times in the last 15 years. Each time surgeons opened up his chest, stopped his heart and put in new valves to replace the old worn ones.

Lau suffers from Marfan syndrome, a rare disease caused by a genetic mutation that weakens the body's connective tissue. Hong Kong maintains no official record of people detected with Marfan syndrome. Doctors know little of the disease. There are no special facilities for patients suffering from the rare disease.

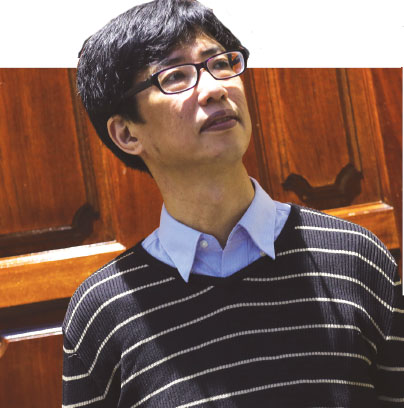

"Hong Kong attaches the least importance to genetic diseases, or the so-called rare diseases, compared to other economies. No special measures have been implemented, even for the detection of rare diseases," says Lam Ching-wan, clinical professor at the Department of Pathology, Li Ka Shing (LKS) Faculty of Medicine at the University of Hong Kong. Lam has been researching rare diseases for more than 20 years.

"I felt like I was left behind by society. The feeling caused me and my family a lot of pain," Lau says.

Lau doesn't have the visible appearance of someone with a serious illness. At six feet two inches, lanky and leggy, he's taller than average. "I was taller than my teacher by the time I got to Form Five," says Lau. His parents and two brothers are way shorter than he is.

Being tall was considered an advantage. Lau was chosen for the school basketball team, exercised a lot, and was good at tennis. Everybody thought he just grew faster than the other kids.

One night in 2001 he felt a terrible pain in his chest. Lau was shocked. He had a physical checkup the month before and was judged in perfect health. He went back to the doctor the next day for a second checkup.

"The doctor asked me three questions," Lau remembers, "Do you smoke? Do you drink? And do you have a family history of heart diseases?" He answered no to all.

"Then the doctor gave me his diagnosis - gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)," says Lau. GERD is a disease of the stomach which can cause severe chest pains. Sometimes it causes heartburn.

Lau was given a gastroscopy - a probe of the stomach. There was nothing wrong with his stomach either. The doctor sent him home with a clean bill of health. Lau was no better, really. Later the diagnosis of GERD was proven incorrect.

Diagnosis errors

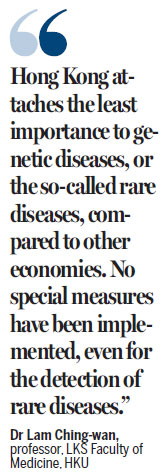

"The chance of misdiagnosis in rare diseases could be more than 80 percent," Lam said, citing his own research data. "That definitely affects patients' health. Sometimes it leads to early and often sudden demise."

In 2001, Zhu Gang, a main player in the Chinese national volleyball team died of sudden rupture of his aorta. He was in his 30s. In 1996, Jonathan Larson, famed American choreographer and winner of a Tony Award and a Pulitzer Prize, died unexpectedly. Doctors later concluded Larson died from undiagnosed Marfan syndrome.

Lau said had he not gone back to the hospital for another test after experiencing chest pains, he might have died. A CT scan showed significant swelling of Lau's aortal veins leading to the heart. The aortic diameter of people at Lau's age is about two or three centimeters, while Lau's had reached eight centimeters. The aortal veins could have burst at any time.

"A doctor told me that I needed surgery immediately, or I would die." Lau recalled. That night surgeons were called back to the hospital to perform an emergency operation.

Doctors suspected it was Marfan syndrome but couldn't be positive without further examination. Marfan syndrome requires a gene test to establish a definitive diagnosis. Weakness of the connective tissues may lead to the dysfunction of other organs, the cardiovascular system, the eyes, even the bones.

"His body is like a house built with inferior cement. Once the cement is non-functional, all parts are affected, leaving the entire house ready to fall down," explains Lau's wife Olga Chew. They were married only two years when Lau had his first surgery. Chew, however, put on a brave face and promised Lau her lifetime support.

A hazy area

The Marfan Syndrome Association in Hong Kong states that one in 5,000 people have the syndrome, citing statistics published by the National Marfan Foundation in the United States. That would point to about 1,400 cases in Hong Kong, assuming they are alive. But these obviously aren't official figures.

The city does not have a database of statistics nor an official definition of the about 6,000 other rare diseases identified globally.

According to the World Health Organization, in every 10,000 people, 6.5 to 10 suffer from rare diseases. That implies that in Hong Kong about 45 newborn infants every year are born with a rare disease, extrapolated from births averaging 45,000 per year, says Lam, the pathologist from the University of Hong Kong.

"But the actual number must be higher. Some patients may die before they are diagnosed... 150 to 200 rare diseases have been diagnosed in Hong Kong but the actual number is higher.

"There is no special hospital for genetic experts in Hong Kong. Doctors who are not specialized in genetics have difficulty verifying rare diseases." Lam explained. "The courses taught in medical schools cover only the most common diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. It all depends on whether or not a doctor has knowledge of rare diseases (related to the symptoms)," Lam added.

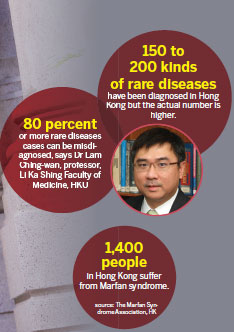

Only six medicines for four kinds of rare diseases are listed on the Hospital Authority Drug Formulary. Patients authorized to use them are given financial assistance. Taiwan, however, has identified 204 rare diseases and established specific definitions for them. Taiwan provides 85 medicines for about 1,000 rare-disease-afflicted patients as of December 2014.

Due to the lack of market demand and because of the prolonged research and development phase, private pharmaceutical companies seem to be disinterested in producing medicines for rare diseases.

Even the medicines listed on Hong Kong's Hospital Authority Drug Formulary aren't always available. Neither are specialist doctors under the Hospital Authority ready to prescribe these.

"Only if the team confirms that the medicine will benefit a patient in a specific stage of the disease in an obvious way will they authorize that medicine," said Lam. Even he won't be able to predict whether or not a medicine might have a specific impact on a patient, he added.

New rights group

The last day of February is marked as International Rare Diseases Day. The Hong Kong Alliance for Rare Diseases was established on that day this year, with a mission to urge the government to protect the human rights of this largely unrepresented group.

Chung Hon-yin, clinic associate professor at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University of Hong Kong, joined the association as a board member. A specialist in clinical genetics, Chung has been actively involved in training frontline doctors and nurses.

"Early detection and even early diagnosis are significant to a patient of rare disease. I would like to vouch for this smattering of a voiceless group," Chung says.

Lam says an undiagnosed disease program at the medical school of the University of Hong Kong, has been providing clinical help to patients with rare diseases since November 2014, on a two-year grant from the S.K. Yee Medical Foundation.

"Before I know I have Manfan syndrome, I had a long-term plan for my life. But now I'm living in a different way," says Lau, who was just notified by his doctor that he will require further cardiac surgery in the next two or three years.

He cannot allow himself to think of a long-term future but must live for today. He says he is happy and he considers the quality of life to be of higher value than his life expectancy. He and his wife quit their jobs three years ago. Together, they are pursuing what interests them the most. "We're now learning ceramics, photography, drawing," say Lau, who breaks into smile talking about his wife. "I'm like a bomb that may explode at any time. But I have no fear now."

Contact the writer at sylvia@chinadailyhk.com

|

Steve Lau, who suffers from Marfan syndrome, and his supportive wife Olga Chew (in picture above) have decided to make the most of the time they have together, by engaging in creative activities. Edmond Tang /China Daily |

|

A patient of Marfan syndrome demonstrates how the disease has made the fingers grow unusually long - a condition called "spider fingers". Provided to China Daily |

|

Professor Chung Hon-yin of HKU and Steve Lau at a conference hosted by the Marfan Syndrome Association on March 26, where Lau shared his experience with the audience. Provided to China Daily |

(HK Edition 04/01/2015 page8)