Pushed to the brink

Updated: 2015-03-25 07:34

(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

As Tai Hang Sai Estate - where some of the district's poorest and elderly have lived for decades - gears up for redevelopment, Andrea Deng asks if the govt should help those facing imminent displacement.

The moldy smell permeates a 100-square-feet room as spring brings heavy moisture to this half-century-old Tai Hang Sai Estate. In this shabby office of Tai Hang Sai Residents' Concern Group, furnished with only a couple of folding chairs, the smell didn't appear to bother the four residents, discussing the galling worry that their lives might end up sinking into a financial morass and possibly homelessness.

Built in the 1960s by 10 "gentlemen" of prominence and wealth, Tai Hang Sai Estate has traditionally been home to some of the district's poorest families, including elderly, single people too old and sick to get out of bed.

Life is not perfect here, but it's easier, living with rents between HK$500 and HK$1,600 a month. Even the city's notorious "cage houses" - subdivided flats, infamous for cramped, poorly-ventilated living spaces - would cost a good deal more.

Back in 2010 the residents of the 1,300 households at the estate had eagerly anticipated a word from the Town Planning Board, announcing a renovation of the premises. And then they were told that when the said renovation happened they might not have a place in the housing any more.

Secretary for Transport and Housing Anthony Cheung Ping-leung stated clearly that the government took no responsibility for the resettlement of the people living in Tai Hang Sai Estate, privately owned by the heirs of the 10 "gentlemen", operating as the Hong Kong Settlers Housing Corporation. The non-profit, charitable society is headed by David Li Kwok-po, chairman of the Bank of East Asia, and Lee Shau-kee, chairman of Henderson Land Development.

Unaffordable rates

The owners offered residents a chance to purchase their rebuilt homes, 30 percent below market price. Residents who agreed to purchase the renewed houses would be temporarily resettled in some of Tai Hang Sai's empty units, free of charge, before the renewal project is completed in roughly five years.

The reaction of residents however was strongly averse, leading to outrage and even despair.

"How am I supposed to afford the house, even if it is 30 percent off?" said Lau Cheung-tai, 65. "Just because we can live here for five years without paying rent doesn't mean that we're lucky. What about five years later? Where is my family going to live?" Lau asked, rhetorically, while other residents concurred.

The current market value at Tai Hang Sai, adjacent to Shek Kip Mei MTR Station, is estimated at roughly HK$13,000 per square foot, said Leo Cheung Shing-din, an estate surveyor.

Lau is a retired renovation worker who saved barely enough to fend for his family. His wife works at a barbecue restaurant in nearby Sham Shui Po. She gets HK$38 an hour.

The average household monthly income of residents in Tai Hang Sai is less than HK$20,000, said Tam Kwok-kiu, vice-chairman of Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood.

Lau's son is currently preparing for his university entrance exam. "If he's lucky, he will be enrolled in university, and we will have to pay his tuition fees. If not, without a university degree, I don't know how much he could earn after graduation," said Lau.

The owners offered a second option - a compensation payment of HK$200,000 for residents prepared to move from the estate for good. Furious residents did the simple math showing that the compensation, combined with their own savings, will be spent on paying the rent in five years.

"How much is the current monthly rent of a 100-square-feet subdivided house? HK$4,000?" asked Lau.

"It's already more than that," said Au-yeung Kit-chun, chairwoman of the Tai Hang Sai Resident's Concern Group.

Ms Ho, a timid 61-year-old, muttered if she should not go for a public housing unit for single people, which costs about HK$900 per month.

"You should get the HK$200,000 compensation then," said Au-yueng. "Don't procrastinate. Uncle Four (Lee's nickname) will have one less person to be accountable for."

Au-yeung herself is a single mother. She works at a kindergarten earning a little more than HK$10,000 a month. She will retire in two years, with about HK$400,000 in accumulated pension from her employer. That would put Au-yeung above the asset limit for public housing applicants. She still wouldn't have nearly enough to buy her own place, even at a 30 percent discount.

Her daughter, just graduated from university, is earning about HK$17,000 a month. Mother and daughter may be forced to move to a private rental unit. "I imagine that if we're to live in one of those sub-divided rental places, we would be miserable. Everyone knows about the horrible conditions of a subdivided apartment," said Au-yeung.

Households like Au-yeung's account for a third of all the residents in Tai Hang Sai, she said.

Ah Man, a young man who was checking on his phone, told everyone about the income and asset limit required for applying for a public housing unit.

"Ouch ... Hopeless. I'm not qualified," Ho looked disappointed. Her saving exceeds the asset limit for a single person applicant, which is HK$221,000.

Even for those eligible for public housing, it might be long wait. Current average waiting time to be allotted public housing is roughly three years, as more than 250,000 eligible applicants are on queue.

Scant compensation

Providing affordable housing and finding land to build these are top priority for the HKSAR government.

Identifying urban renewal project has been one of the sources of residential land supplies, among other sources, including development of vacant land in urban area as well as farmland in the New Territories, the government said. Yet more often than not, affected residents of urban renewal projects receive minimal financial compensation while having to leave homes they had lived in for decades.

Residents in some parts of Pak Tin Estate, a public housing estate in Sham Shui Po built in the late 1960s, were told in 2012 to leave in 24 months, so that the government could renovate the estate to accommodate 5,650 households. Residents were compensated for only 18 months of rent and had to relocate to other districts. Store owners were distraught that their businesses would have to shut down for good, losing millions of dollars. They were only compensated HK$99,000 on top of 18 months' rent waiver.

Though Tai Hang Sai is not situated on government land, some politicians and property experts believe the government should play a role in helping the estate's residents.

During this year's Policy Address, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying specifically mentioned Hong Kong Settlers Housing Corporation as one of the housing institutions that the authority should engage, in order to provide low and middle-income families with "more property choices and home ownership opportunities".

Uncle Four made a timely announcement the next day that he intended to turn Tai Hang Sai Estate into something like a Home Ownership Scheme development for "hard-working youngsters". He proposed a sale price of HK$1.3 million per unit for qualified young people at the low or middle income level.

The plan, according to Tam, was never raised again, after residents reacted angrily to the resettlement proposals. Residents - more than one-third of whom were over 65 - were also upset that the plan favored young people against the elderly, Tam said.

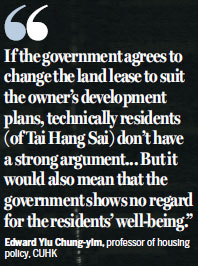

Meanwhile, the current land lease of Tai Hang Sai says that the estate must provide affordable rent to low-income families. The Corporation remains a non-profit company enjoying tax-exempt status. Edward Yiu Chung-yim, associate professor of housing policy and real estate economy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said if the Corporation remained under its existing charter, the proposed resettlement plans for residents would be "far from enough for it to fulfill its social responsibility".

"If the government does provide any sort of subsidy for this renewal project, or if there remains a tax exemption, the Corporation must continue to provide low-rent residences to low-income families, after all it involves taxpayers' money," said Yiu.

Nonetheless, this half-century-old land lease very likely will be changed before the renewal project can commence, whether the Corporation is to offer housing to young people or to current residents below market value, Yau said, and that really depends on how the government intend to set the new land lease.

"So if the government agrees to change the land lease to suit the owner's development plans, technically residents (of Tai Hang Sai) don't have a strong argument, because it becomes a de facto private operation. But it also would mean that the government shows no regard for the residents' well-being," said Yiu.

Contact the writer at andrea@chinadailyhk.com

|

More than half the residents in Tai Hang Sai Estate are retired or about to retire. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

Tai Hang Sai, which locates right by the Shek Kip Mei MTR Station, has a high property value if fully developed. |

|

Tai Hang Sai Estate, established in the 1960s, is urgently in need of reconstruction. |

|

Residents of Tai Hang Sai Estate apprehend that renovation of the premises would force them to relocate to costly sub-divided flats, and end up in financial distress. |

(HK Edition 03/25/2015 page7)