A crossing and a bridge

Updated: 2015-03-20 07:10

By Chitralekha Basu(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

The Script Road festival turns the spotlight on the diverse literary efforts that are shaping Macao's emerging new cultural identity. A report by Chitralekha Basu.

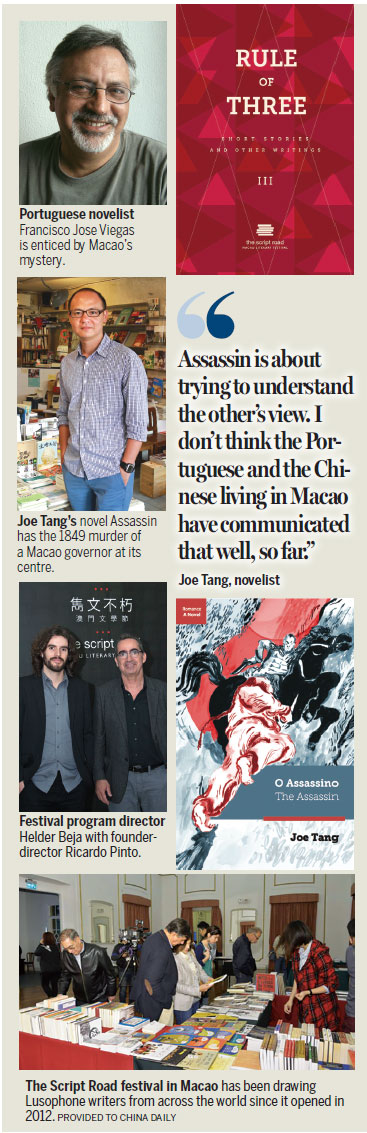

Macao-based author Joe Tang remembers the pilot edition of The Script Road festival in 2012 rather well. And not just because it was an opportunity for him to meet Lusophone writers from Brazil, Africa or Portugal - people writing in a language which he has heard often enough in passing, being a resident of the erstwhile Portuguese colony, but never quite managed to engage deeply with.

Neither did the festival do much to notch up the sales of his books, although Tang happens to be one of Macao's most-awarded literary figures. Given the scant presence of commercial presses, the absence of literary agents and with not much of a reading culture, "literature from Macao has a very small market, anyway," says Tang.

One of the biggest surprises from the first Script Road, however, he says, came after it was over. In an anthology, titled First Things First, published by Praia Grande Edicoes, in which visiting writers were invited to contribute, the novelist Lolita Hu wrote a story set in a Macao casino, about a wealthy Chinese woman's tryst with a Portuguese toy boy. She brought an insight and immediacy to the story that threw even a seasoned Macao hand like Tang off-kilter.

In three languages

One of the unique aspects of The Script Road - Macao's very own literary festival whose fourth season took off yesterday and runs until March 29 - is its tri-linguality. "Each word that we release, from program notes to post-event compendiums of media reports, is in three languages - Chinese, Portuguese and English," says the festival's program director Helder Beja. For about 500 years - since 1557 when Macao was officially ceded to Portugal as a trading port - the Portuguese and Chinese have co-existed in this picturesque seaside town, taking each other's cultural heritage for granted to a large extent. The Script Road festival was started by publisher and former journalist Ricardo Pinto primarily as an attempt to bridge that gap - bring the Chinese and Portuguese-speaking communities of the world closer to each other through a celebration of the written word, which has since been extended to films, music and cuisine. Translating between Chinese and Portuguese - which Pinto sees as a mission - was found to be much smoother through the mediation of English, hence the inclusion of the third language.

The difference in sensibilities between a Chinese and a Portuguese, says Beja, is all too apparent in the short fiction contest they have been running as a part of the festival. "While the Portuguese approach the city with a sense of strangeness, exotica, for instance they would write about bizarre funeral traditions, temples, 'Oriental beauties', transcendentalism, the Chinese tend to prefer stories of social realism. They write about the casinos, satirical pieces about the rising prices in the realty market," he says.

Joe Tang's own writing does not quite fit into either category. His new novel Assassin, which will be launched in a trilingual edition during the festival this year, is based on the 1849 killing of Macao governor Joao Maria Ferreira do Amaral, one of the most gruesome political murders in Macao's history. The one-armed Amaral was decapitated by a rebellious Shen Zhiliang after the former's heavy-handed treatment of the Chinese natives made him extremely unpopular.

This was a story Tang knew he had to handle sensitively. "The Chinese and Portuguese have different views on that incident. And in a lot of ways that event determined what Macao is today, socially, economically. I didn't want to sit in judgment," he says. Each of the story's three protagonists is shown trying to carry out the responsibilities he is vested with. Nobody is a villain. "It's about trying to understand the other's view," says Tang. "I don't think the Portuguese and the Chinese living in Macao have communicated that well, so far."

Reviving Macao patois

One way of building bridges between cultures is to find a common lingo. For 20 years, playwright and director Miguel Fernandes, who runs the theater group Doci Papiacam di Macau (sweet language of Macao), has been trying to open up a channel of communication between the two cultures by writing Macao patois into the dialogues of his plays. The hybrid language that grew out of mixed marriages and would be heard about 50 years ago began to lose its currency in the 1980s, "primarily because it was considered a language of the lower classes," says Fernandes, "or one that belonged in the domain of women."

In his plays - Vila Paraiso (Paradise Village), Qui Pandalhada (What is it, Doctor?) - Fernandes introduced a smattering of Macanese patois which the audiences have since picked up and made a part of their everyday speech. "The words are in Portuguese but the idiom is Cantonese," says Fernandes. "Take the expression, 'vai-vem', for instance, which literally means back and forth, suggesting the person in question is unstable, undecided or reckless."

While it's absurd to expect people to start speaking in Macanese patois again, Fernandes feels it is important not to forget the shared histories of the two languages. "My aim is to make people aware of a past. I'm trying to revive a collective memory," he says.

The revival of Macanese patois is indicative of the city's new emerging cultural identity. Macao is changing - drastically and dramatically. "Traditional jobs and industries are disappearing, people running small businesses are being forced to shut down, young people are dropping out of schools to work in casinos," says Pinto. The writers featured in this year's festival will, doubtless, reflect on these changes. Besides locals like Tang, the noted Portuguese writer Francisco Jose Viegas, whose forthcoming novel is set in Macao, would likely be holding forth on the city's enduring appeal in terms of its "enigma, mystery and loneliness, in the literary sense".

"I think a new identity for Macao can only be built on the basis of literature," he says. "There is no identity without literature, and The Script Road is a fantastic opportunity to explore that theme."

"Maybe one of the most specific elements of the so called 'identity' of Macao is its capacity to change and adapt to new circumstances, the so called 'fluidity' that gives the city its post-modernist face along with the capacity of showing multiple, contradictory layers of culture, experience and lifestyle," adds Fernanda Gilcosta, head of Portuguese Studies, Macau University. The Script Road festival, she says, is a great platform for showcasing "the continuous encounter of cultures, the weight of tradition and the appeal of modernity" which falls in line with "Macao's traditional mission as a crossing and a bridge of cultures".

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 03/20/2015 page10)