Entering the forbidden zone

Updated: 2015-02-04 10:03

By Sylvia Chang(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

As Sha Tau Kok oFFcials actively liaise with the newly established development bureau in Shenzhen, the village located in between is on the lookout for a historic transition. A report by Sylvia Chang.

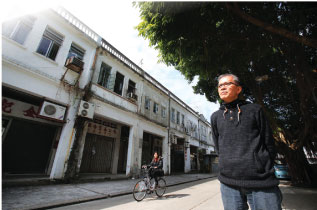

'Welcome to the village of two systems," Tsang Yuk-on declares as he steps onto San Lau Street, Sha Tau Kok Village, far end of northeastern New Territories.

Tsang, 60, executive member of Sha Tau Kok District Rural Committee, is standing on the frontier between Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Several meters away, parallel to San Lau Street, is the well-known Chung Ying Street (or, Sino-British Street), 250 meters in length, marking the line of demarcation between the two sides.

On the fringe of the closed border area, Sha Tau Kok Village has been a highly sensitive barometer of the relationship between the mainland and Hong Kong. Each time Hong Kong-mainland relations changed and new policies were formulated, the village would receive a drastic makeover.

Since 2012 the Hong Kong government has been gradually opening up the frontier area, but Sha Tau Kok Village remains in a forbidden zone. With the mainland moving rapidly towards its ambitious economic target and Hong Kong struggling with its post-colonial identity, the village in between is in the throes of a historic transition.

There are 22 two-story houses, lined up on one side of San Lau Street. The houses, made of wooden planks painted white, are linked by large pillars which form a long verandah. The rooms on the top floors are the living quarters. The lower floors used to house shops - identified by plaques proclaiming expertise in gold, porcelain, furniture, electrical equipment and household stuff. These represent the golden era of commerce in the community. The plaques today are worn and shabby, and the shops long shuttered behind iron gates.

Back in the days of Deng Xiaoping's free-market policy, initiated in 1978, development was intense in the border area. Sha Tau Kok Village back then was a commerce center bustling with mainland people buying Hong Kong-made products from local villagers.

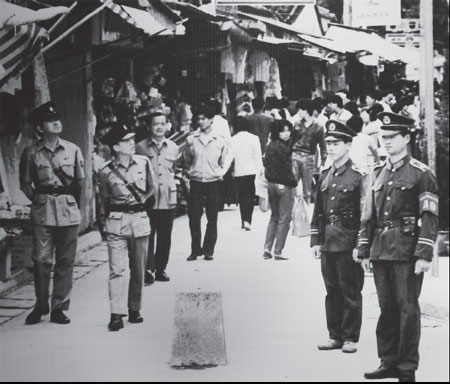

Chung Ying Street drew 100,000 visitors a day when business was good. A company on San Lau Street could sell out about 500 bolts of cloth a day in the 1980s, writes Lau Chi-pang, associate professor at the Department of History at Lingnan University in the book Collected Memory of Chung Ying Street.

Poised for change

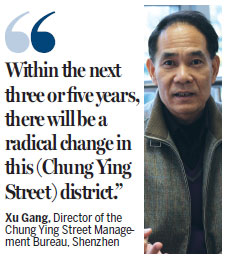

On Dec 16, 2014, the Shenzhen Yantian district government announced the establishment of the Chung Ying Street Management Bureau, an administrative unit mandated to shape the frontier district of Shenzhen into a "strategic fulcrum of economic development" in southern China.

"Within the next three or five years, there will be a radical change in this district," said Xu Gang, director of the Chung Ying Street Management Board with confidence. He is expecting to achieve a "new era of glamour" in the border area with "common development and prosperity" of both Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

As officials of the newly established bureau and members of the Sha Tau Kok District Rural Committee begin their interactions, Sha Tau Kok Village, formerly a border free trade zone and now an almost forgotten enclave, faces another watershed.

Since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), most areas of Shenzhen and the Hong Kong territory belonged to the same district. Most indigenous inhabitants of Sha Tau Kok Village are Tanka and Hakka people who migrated from southern China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Before the establishment of the People's Republic of China, villagers in the frontier area were mostly farmers who passed freely across the border to Shenzhen.

In 1951, the British colonial administration of Hong Kong issued a Frontier Closed Area Order, sealing the border across 2,800 hectares. Entry to the closed area was restricted to those holding a pass.

The registered residential population in Sha Tau Kok Village has reached several thousands, Tsang estimated, "but in reality, less than a thousand people are living here," said Tsang.

Hong Kong residents may rent a house in the village, allowing them to apply for a permit to carry on trade on Chung Ying Street. "But after getting a permit, most people moved to the urban area of Hong Kong or to live on the mainland."

"The village is dying," Tsang added.

The space in between

Along San Lau Street runs a narrow ditch, pouring raw sewage into the Starling Inlet Sea. During ebb tide, the ditch gives off a pungent stink that hangs over the street like a blanket. From the other side of the stone wall, people from the mainland gaze toward San Lau Street through the railings.

Two soldiers in their green uniforms stand on the Shenzhen side. Only Sha Tau Kok residents who hold a special permit are allowed to pass. Mainland people from Shenzhen also need a permit, a different one, known as the "bridgehead paper", to access to the street.

About 50 meters away from the checkpoint facing San Lau Street, stand four or five wooden houses on stilts above the ditch. Most are deserted now except for one that serves as a stall selling items for religious use. The space inside - less than 5 square meters - is piled with candles and joss paper money.

The household belongs to the Ngs, an indigenous family. A woman in her 30s jokes that they have been "hiding" here for decades. They cook in the stilt house using an induction cooker every day and go back home in a town nearby, reachable only by boat.

An iron railing inlaid in the stone wall on Chung Ying Street coincides with a window of the Ng family house, through which business is conducted.

Ng says that she has seen plenty of smuggling on the street outside her house. "Wine, drugs, cigarettes - all kinds of smuggling," she says.

"But we've never had illegal trade for all those years. Never," Ng's mother emphasizes, pointing to the two cameras used to monitor smuggling and illegal immigration, set outside her house.

Ng is quite annoyed by the fact that nobody had asked their permission to build a stone wall right against their house. The lone "window" spared for business, she says, "was an award for our long-term honesty".

Most of the customers are old familiar faces. "For all these years since the reunification, business has been falling sharply. The situation got worse once the travel policy was applied," says Ng, referring to the implementation of the Individual Visit Scheme by the Hong Kong government in 2003 which allows people from big mainland cities to visit Hong Kong without joining a travel group.

"If the area was going to be opened to the public, there would be more frequent smuggling," Ng said, concerned about her family's safety in such an eventuality.

Uncertainty looms large

The date for excluding Sha Tau Kok from the closed frontier areas has not been set yet, said Lee Koon-hung, chairman of the Sha Tau Kok District Rural Committee.

"This is a good place for hiking and boating. The farthest island could be reached within half an hour by boat," said Lee, indicating the islets around the harbor of Starling Inlet.

"Right now Chung Ying Street is nothing but a distribution center for smuggled goods," said Lee, hoping to see the district serve as a "gateway" to a popular tourist spot instead.

Standing on the Sha Tau Kok public pier, Tsang, points to the Shenzhen Yantian People's Government offices. Not far away a former Soviet aircraft carrier Minsk rests at permanent anchor in Shenzhen's military theme park.

"Thirty years ago there were only a few houses over there. But now 40-story skyscrapers are being built here," said Tsang.

On the other side of the pier, the wide and uninhabited mountains of Hong Kong tell a different story of the same district. Fishing boats dot the sea surface, glowing red and yellow at the sunset.

Contact the writer at sylvia@chinadailyhk.com

|

A ragged wooden house stands above a ditch in Sha Tau Kok village, Hong Kong. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

Tsang Kuk-on on San Lau Street, formerly a prosperous border free trade zone and now an almost forgotten enclave. Edmond Tang / China Daily |

|

The checkpoint on the Hong Kong side to Sha Tau Kok village. Visitors all need a special permit to gain access. |

|

Shenzhen patrolling at the same time on Chung Ying Street in 1985, a time when commerce was intense in the border area. |

|

Police from Hong Kong |

(HK Edition 02/04/2015 page7)