Living on the margin

Updated: 2015-02-03 06:36

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Childhood does not treat everyone equally. Ming Yeung meets a few young people whose early struggles have helped increase their determination to work toward a better future.

Wong Man-lai

In an old black and white photo Wong Man-lai stands, looking over his shoulder, smiling, despite the looming crisis in his life. It's the same shy smile he wears today. The photo was taken when his father, weak and dying from diabetes and kidney failure, looked to his son, holding the machine for his dad's dialysis.

Today Wong Man-lai reckons he needs only a few more years' hard work to break the cycle of poverty that has plagued him and his family through most of his life. He's going to open his own art studio. At 21, Wong seems to have grown up fast. Maybe it was poverty and having to fend for himself at such an early age.

Ten years ago, Wong would be out collecting discarded bits of cardboard and cans, to supplement the family's meager income. "If I was lucky, I found a toy in the trash," he said, without self-pity, a tad amused, in fact.

Wong and his parents lived in a cramped, subdivided flat in Sham Shui Po. The bathroom and kitchen were shared with other tenants. Wong and his mother moved here in 2000 from the mainland. Wong's father got a job as a security guard. It was short-lived. Soon afterwards he was overtaken by poor health. Doctors amputated his legs.

The old photo of Wong and his dad is one among the 26 included in Treasure, a photo album published by the Society of Community Organization (SoCO) 10 years ago. Treasure was a project to raise public awareness of child poverty. Sham Shui Po was the poorest district in Hong Kong, with more than 67,000 people living under the poverty line.

Wong was in primary six when his father died. "Maybe I should not say this, but life got better after that," Wong said. "The burden of taking care of him, physically and financially, was relieved." SoCO provided food vouchers and used clothing to them from time to time.

There was no entertainment. Wong passed the time drawing on sketchbooks and textbooks, and just about any piece of paper he could find. His talent was recognized. He studied visual art from Form 4 to Form 6 and when his public examination results proved him no scholar, he was channeled into design studies at a vocational training institute.

It seemed things were beginning to look up, but then the three-year course was cancelled after Wong's first year, due to an insufficient number of students.

The course supervisor had found Wong a part-time job teaching kids to draw. And when the course was canceled, Wong started working at the children's center full time.

Wong is optimistic about his future and achieving his goals.

"I don't feel that those who come from wealthier families ought to work less hard to achieve what they want. We all start on the same starting line. I just do my best," he said.

|

At 21, Wong Man-lai reckons he needs a few more years' hard work to break the cycle of poverty and open his own art studio. Provided to China Daily |

Lan Mei-ling

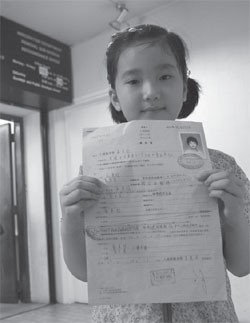

A Form 5 student today, Lan Mei-ling, wearing a big pair of glasses and a bigger smile, proudly holds up her Hong Kong identity card. She has a right to be proud. The identity card was a hard-won prize. It took her a long time to get it and she sees a big future in it. She wants to become a police officer so she can arrest her deadbeat dad who didn't provide her documentation and left her almost stranded on the mainland.

Lan was born on the mainland in 1997. When she was 5, her mother, Huang Lanying, was granted a one-way permit to move to Hong Kong to be reunited with her husband, a Hong Kong resident. The little girl's application failed. A paternity test was needed to establish her eligibility. Her father didn't tender the documents she needed.

Lan was relegated to "no-document" status. She got a temporary permit, a so-called "going-out pass", so she could stay in Hong Kong. Her mother enrolled her in a kindergarten but when it was time for Lan to move on to primary school, the doors were closed on her.

Huang wrote letters to the Immigration Department, with the help of SoCO, making a desperate plea for Lan's right to an education. Lan's application finally was approved at the discretion of the Director of Immigration.

There's a photo of her in Treasure, holding her temporary permit half-way up her chin, smiling shyly at the camera, outside the immigration office.

Lan was continually reminded of her ambiguous position. For example, when her classmates were getting their compulsory dental checkups, Lan, not being a Hong Kong resident, wasn't entitled to the benefit given freely to her classmates.

"Without a Hong Kong identity card, I wasn't entitled to receive any kind of benefits, not even the book subsidy, and it was particularly difficult for mom," she sighed.

Lan remembers the first few years living in a partitioned flat in Kwun Tong. Lan, who is fastidious about cleanliness, found the place disgusting, especially the toilet that was shared with other tenants.

"My mom had to clean it up before I took my shower," said Lan, who blames her absentee father for her suffering and poverty. "I have no feeling about this man but I know it was entirely his fault. Since we have come to Hong Kong, he has never taken care of us," said Lan. "He treated us like strangers. He even called the police to kick us out."

Her father disappeared after he and Lan's mother were divorced in 2006, allowing him to avoid making support payments.

Her mother earns HK$8,000-HK$9,000 a month, their only source of livelihood. Lan hopes to make big money in the future.

"Ah! I remember what I wanted to do," she exclaimed, laughing. "I wanted to be a police officer to arrest my father!"

|

Lan Mei-ling has a close relationship with her mother, Huang Lanying, as both were abandoned by her absentee father. Provided to China Daily |

Khem Limbu

Khem Limbu is Nepalese by birth, but uncomfortable with Nepalese lifestyle and customs. "I don't particularly like to mingle with the Nepalese community," Limbu said. "Perhaps I didn't hang out with them much, so I lost the interest."

Neither did he have a good grasp of Chinese, a subject he needs to pass in public examinations to be able to make it to university.

Limbu, now a student set to repeat his Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) examination this year, migrated to Hong Kong in 1997 at 6 months old.

He is puzzled by some of the secluded ethnic minority members who refuse to learn and assimilate to the local culture.

Although his family is relatively better-off today, life was not easy 10 years ago. Limbu, however, thinks he had a healthy childhood. He enjoyed hanging out with the local kids, playing yo-yo in a playground on the weekends.

Having a darker skin tone than Chinese but lighter than Nepalese, other kids regarded him as a strange "hybrid".

"That's how I learned to speak Chinese," the wiry young man said. "They were all Chinese and we could only communicate in Chinese."

Speaking fluently in Chinese, though, doesn't guarantee a high level of proficiency in the language, let alone a satisfactory result in the public exams, especially since his parents and grandfather speak Nepalese and English only.

"I wish we had more Chinese classes. We were lucky to have some volunteers at SoCO helping us out," said Limbu, who feels his Chinese proficiency is far below satisfactory, although he has no difficulty reading Chinese newspapers and Web pages.

Like his fellow countrymen, Limbu studied at Delia Group of Schools, which specializes in education for ethnic minority students. In Treasure, Limbu shows off a certificate of merit, a proof of his outstanding academic performance in Chinese.

Today, with the same posture, Limbu shows his DSE examination result, insufficient for public university placement.

He is not too bothered about the program of study, as long as it is an undergraduate placement.

A university certificate is simply an entry ticket for him to land a job that might earn him a fortune.

"Actually I don't have a dream. All I want is to make more money. The more, the better. It's for self-satisfaction, perhaps," he said, with a wry smile.

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

Nepalese-born Khem Limbu lives happily with his parents and grandfather. He speaks fluent Chinese and feels more at home with his Chinese friends. Provided to China Daily |

(HK Edition 02/03/2015 page7)