Something like a painting

Updated: 2015-01-16 05:30

By Chitralekha Basu(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

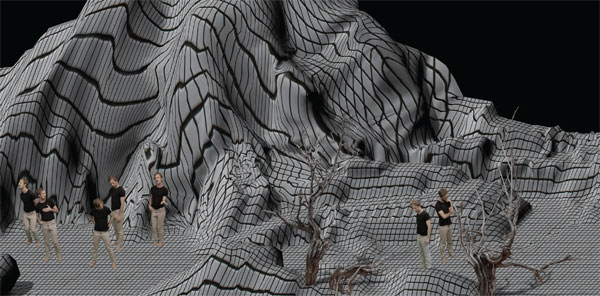

In Extensions of a No-Place, the artist figure explores and reveals the narratives of space. Provided to China Daily |

In a show coming up at HK's Hanart Gallery later this month, Australian artist Peter Nelson turns the conventional way of looking at Chinese landscapes on its head. Chitralekha Basu reports.

In Peter Nelson's video installation, titled Extensions of a No-Place, there are five of the artist himself, making up a flash mob, dancing on a grey tiled landscape featuring looming, barren hills and shriveled tree stumps, while two more editions of him stand at a distance, evidently lost in thought. Reflection and contemplation are perhaps key elements in the art show at Hong Kong's Hanart Gallery (beginning Jan 28) - a combination of paintings, sculptures and video art clubbed under Grids and Stones, meant to test and tweak traditional ways of looking at things. It's the fruit of Nelson's continued engagement with traditional Chinese landscape painting and his extraordinary ability to re-imagine these by using tools and methods of contemporary media - 3D projections, video installations, computer games.

Extensions of a No-Place, says Nelson, is inspired by a painting, inspired by a poem, inspired by a memory. It is based on Wen Zhengming's (1470-1559) painting, imitating Zhao Bosu's Illustration of the Latter Red Cliff - an illustration of a Song Dynasty (960-1279) poem by Su Dongpo. "The idea that this landscape painting was already depicting a series of mountains, trees and waterways based on the words of a poet appealed greatly to me," says Nelson. "Wen Zhengming would paint not only using contemporary conventions of his time, but with an attempt to inhabit the memories of a poet who lived hundreds of years earlier."

The original painting, which Nelson saw in Taiwan's National Palace Museum, is a never-ending scroll - a precursor to a comic strip, if you like, in which the poet's journey through the imposing landscape would be difficult to view in its entirety at one go.

"The notion of a landscape painting so long that it had to be explored section by section, inspired my creation of a similarly long computer-generated landscape," says Nelson. He could relate to it, living as he was, in a foreign city, exploring its nooks, alleys and strange unfamiliar spaces, gingerly, a step at a time, not knowing what to expect next. "I could imagine this digital landscape as akin to a computer game in which my character explores and reveals the narrative of the space. When I put myself in the picture in my adaptation of that image, once again it was about discovering the landscape by guiding myself around. It was about both inhabiting and exploring that space."

From down under

He had to put a bit of himself and Australia, where he comes from, in his video adaptation of this archetypal Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) image belonging to the literati tradition from more than 500 years ago. Literati or scholarly paintings are often a narrative in images, showing men of letters immersed in cultural pursuits against the backdrop of imposing mountains and waterways. So Nelson included the typical Black Blue Bush of the Australian desert, heightening the starkness of the grey grid backdrop.

"Like the ancient, twisted pines that perch atop Chinese mountains, these small shrubs will live to one hundred years old and grow only to about 20 cm tall, contorted by age and dwarfed by the harsh conditions of the desert," says Nelson. "The white square tiles representing the Utopian grid are reminiscent of the ceramic tiles of 1970s radical architects (such as the Italian group Superstudio) used. The square and the grid are an important symbol of Utopian thinking."

The fluidity in these squares suggests the possibility of new ideas, new constructs, perhaps even a "new beginning", says Nelson "where our past does not influence our future".

Nelson points out he took his cues from the original. "Recreating Wen Zhengming's landscape, using a variety of different cultural components such as those seemed a good approximation of how his own painting practice would have functioned - taking influence from a wide range of artistic and poetic traditions to create a new landscape."

"The 'Grid'", says Nelson, "is the creation of an artificial space, while the 'Stone' is the primitive inhabitant of that space." Chang Tsong-zung, the director of Hanart Gallery, who contributed to developing the kernel of Nelson's idea, adds his gloss. "The grid", he says, is "based on science and is quantifiable, and upon which the stone, which is non-rational, chaotic and individual, is located. It's a thing that's difficult to pare down to a transparent, rational object."

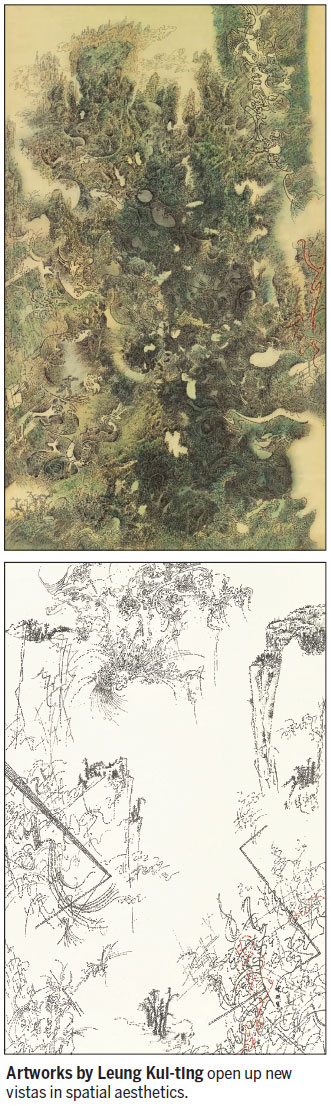

This duality, Nelson feels, applies rather well to the three artists he has chosen to complement his own work in the show - the ink on silk landscapes of Hsu Yu-jen, which look like washed-out charcoal sketches; the intense dovetailing of foliage and undulated terrain representing mountains and clouds in Leung Kui-ting's ink and color on silk paintings and Map Office's sculptures of islands made of oyster shells and wax - colonies in which minuscule figures wander around, exploring a new world.

Map Office famously created an island out of discarded oyster shells chucked on the coast of Lau Fau Shan in the shape of Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale in 2007. Valerie Portefaix, who is one of the French architect duo comprising Map Office, says the idea of creating newer spaces is about challenging the existing use of given spaces - a token of what might be possible in the realm of imagination, if not in actual physical terms.

"In the artworks to be exhibited at the Hanart Gallery, the intention is to create new fictional islands, show workers, golfers, exploring a new terrain and climate. We are looking at the possibility of building new islands in Hong Kong's waters, not so much in our capacity as architects but as storytellers, trying to imagine what it would be to go back to a traditional economy and a pristine island culture," says Portefaix.

Nelson's own work is marked by a similar playfulness. His sculptures of mountains might be mistaken for the plasticine lumps children play with.

These are in fact 3D-printed digital images of a regular painting and cast in celadon ceramic. The idea was to "reinforce the fictional element, extend its imaginary nature" by adding the third dimension to an adaptation of a two-dimensional painting.

"My ceramic mountain, in its abstract form, is nothing like a mountain but hopefully something like a painting," says Nelson.

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 01/16/2015 page7)