Life on the road

Updated: 2014-10-20 07:10

By Chitralekha Basu and Frannie Guan(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

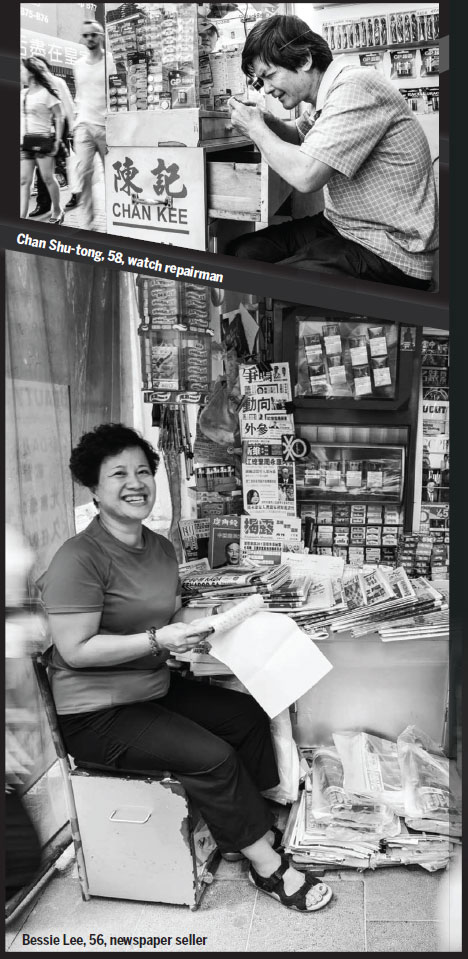

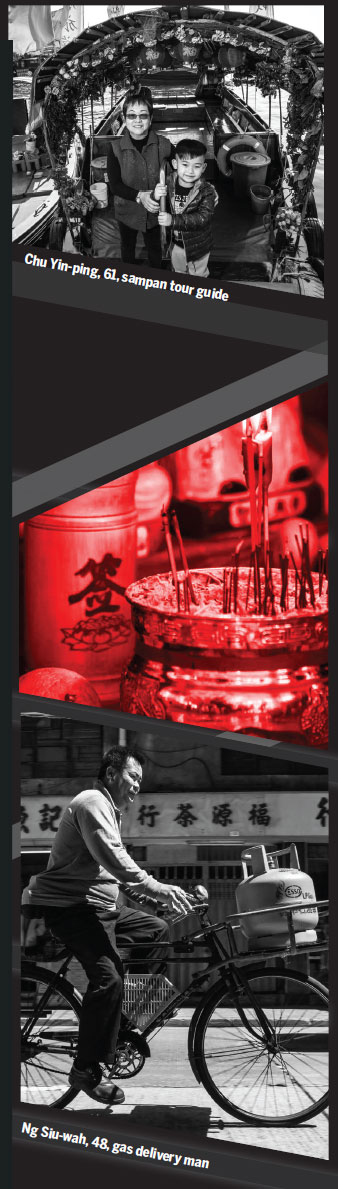

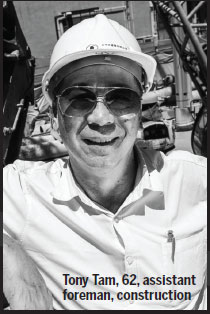

Writer-photographer duo Nicole Chabot and Michael Perini turn their gaze on a myriad range of people who work outdoors to earn their keep in Street Life Hong Kong. Chitralekha Basu and Frannie Guan re-visited two of the 24 personalities featured in the book.

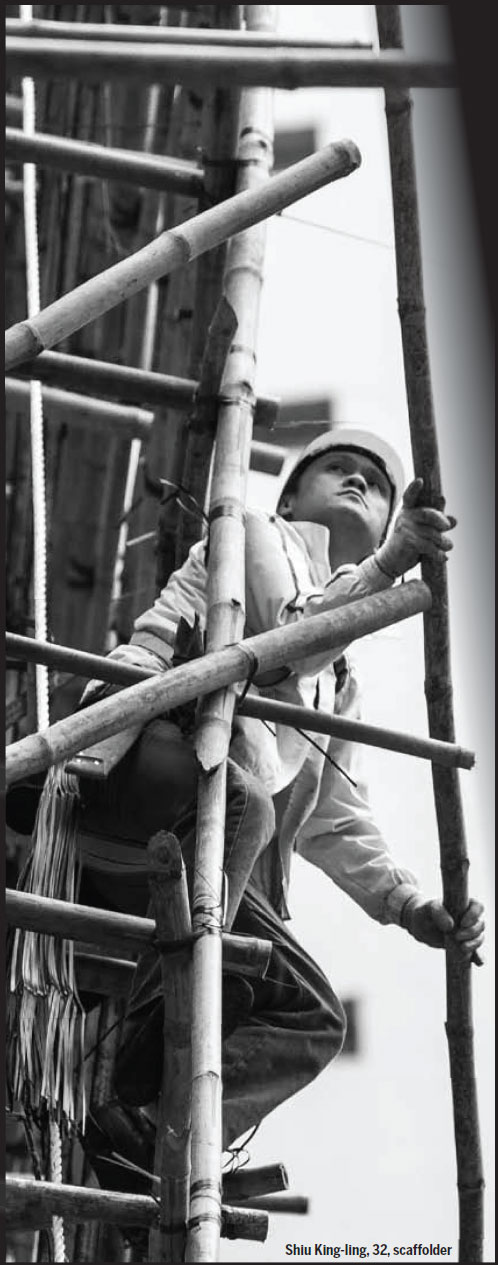

Tony Tam, assistant foreman

Over breakfast at KFC on a Sunday morning, Tony Tam Kwok-chiu was browsing the photographs in Nicole Chabot's book, Street Life Hong Kong. He is one of the people featured in it. "I look old in this photo," said Tony, taking a sip after his wife stirred sugar into his coffee, "but Michael Perini (the photographer) was a professional. He shot really good photos for the book."

Tam is seen wearing a pair of sunglasses in the photo. Five years ago sunglasses became a necessity at work for Tam. His wife said Tam's eyes would water as he worked eight-hour days, most spent standing under the glare of the sun.

Tam is 64 and still going strong. He has worked in the construction industry for almost 30 years and has no plan to retire yet. "I hope to work until 70-something because I have gotten used to my job. Besides, staying at home all the time will be boring," said Tam.

Tam's wife is proud to have her husband featured in Chabot's book, but even more so that he is the backbone of the family. And yet it was not she but Victor Fan, a 29-year-old engineer working on the same project as Tam, who got the first look at the book when it arrived.

"He asked 'why did the author pick you and not me?'" said Tam, who shares a great rapport with his young colleague. Fan, Tam said, was a thoroughbred professional when it came to technical issues like drawing but all the same he had to turn to Tam to find out about the most effective way of executing his designs. The two often have their meals together after work.

Work set-ups have gotten more professional in the last 20 years - a change Tam has been witness to. Earlier workers did not take deadlines very seriously, but now they have to, given that construction companies must pay heavy penalties as high as HK$ 500,000 per day, even if they overshoot the deadline by a measly two days. Tam's work as an assistant foreman is therefore crucial. He ensures the smooth progress of any project, without compromising on quality.

His two sons, now 31 and 35, graduated with engineering-related majors. "We did not dictate what they learned in college or the jobs they took up," said Tam. His elder son remained in industry while the other became a cram school teacher.

Watching TV and betting on horses are the two things Tam likes to do after work. He kept looking at his watch during our interview, ready to rush back home when it was over.

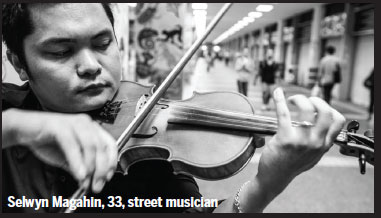

Selwyn Magahin, busker

A slightly-overweight middle-aged Caucasian couple breaks into an impromptu jig. A Chinese girl, evidently a little jaded, on her way back home from work, stops to remove her earphones. Salt-and-pepper haired South Asian men, hooded large-eyed women from the middle-east and sun-tanned white men, fingers interlocked with their long-haired Filipina companions, pass by. Each time one of them bends a little to put a note in his violin case that Selwyn Magahin has left open in front of him. He takes a bow. It's a gesture so earnest that one would think he had just received a standing ovation at City Hall.

But then that's the point of busking, says Magahin, a driver by day, who plays after work at the entrance of the old Central Market, in a corner of the profusely-illustrated corridor leading to the escalator. "A busker does not discriminate between his audiences. You could say I have brought the violin out of the City Hall for the enjoyment of the general public. It's one of the most democratic and human things one could do."

Magahin, who went to Philippine Normal University and used to teach music in schools before he left his hometown not-too-far-away from Manila to seek a better life elsewhere, washed up on the shores of Hong Kong via Macao. Now eight years on, and still without permanent resident status, he cannot imagine where else he would rather be. "There is huge appreciation for music in Hong Kong, including the classical numbers," he says. "It's only here that people will slip you notes, saying 'I'm broke but thanks for your music. You add color to this place.'"

His family - a soprano singer wife, who works as a domestic helper for an American family and their 15-month-old boy - are the dual anchors of his life, to say nothing of the Pentecostal Missionary Church at Sheung Wan where Magahin was married. Much of his life has been about continuous movement - from one country to the other, driving across the length and breadth of Hong Kong, shifting playing locations chased by the local cops ("But I don't blame them," he says, "they're just doing their job."). The worry about not having a fixed address vanishes from his thoughts when he sits down to play the piano at the church on Sunday mornings, he says.

He's all agog about being featured in Street Life Hong Kong. "Now I'll be a part of history, maybe even a ready reckoner for people interested in busking. Those wishing to research the subject are most welcome," he says. "And who knows maybe even someone from the government will come calling, 'Hey Selwyn, we have a place for you in the ministry of music!'"

He laughs out loud at this point. After all, an artist, if anyone, has the license to dream.

(HK Edition 10/20/2014 page7)