Free spirit

Updated: 2014-09-26 08:19

By Chitralekha Basu and Frannie Guan(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

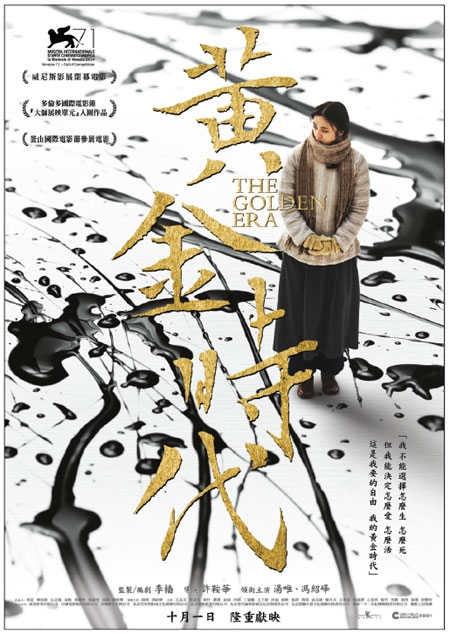

Ann Hui's new film, The Golden Era, turns the spotlight on the bohemian 1930s writer Xiao Hong and the eminent men and women of letters who passed through her all-too-brief life. Chitralekha Basu and Frannie Guan report.

Writer Xiao Hong (1911-1942) was probably an original hippie well before the Beat movement caught on in America. She ran away from her rich landowner father's home in Heilongjiang with a married cousin and when he abandoned her she became a peripatetic writer - moving across Beijing, Harbin, Qingdao, Wuhan, Xi'an, Chongqing, Shanghai and Tokyo, hooking up with several men. In a scene in The Golden Era - a new biopic directed by Ann Hui - Xiao Hong, who is pregnant, abandoned by a supposed fianc, and living in the balcony of a magazine office to which she occasionally contributes - blows her entire savings by buying drinks for friends.

The film, to be released on October 1, is Hong Kong's entry to the foreign-language Oscar race. It follows the extraordinary journey of a writer - probably the first in China to put women at the center of the narratives, often dark tales of familial and societal oppression, told with a Kafkaesque sense of the bizarre.

In the film, Xiao is a restless free spirit. It is her inability to belong to a place or a person that comes across most poignantly. Unmoved when betrayed by the men she loved, she endures moments of excruciating physical agony (like when she is fed through a pipe planted in her neck, recuperating from a surgery in Hong Kong) with complete lack of self-pity. A heavily-pregnant Xiao jumps from a window a couple of floors above, into a boat on the overflowing streets of Harbin. She casually asks the boatman to carry on as if she did that as a matter of routine.

Parting with her newborn children (one is given away in adoption, the other child she has with the writer Xiao Jun dies soon after birth) does not seem to affect her. She seems to have wrung out the last drop of emotions, let it flow through her writings and kept nothing of it for herself. Tang Wei, who had impressed director Ann Hui with her power-packed performance in Ang Lee's Lust, Caution, has essayed the role of Xiao Hong with incredible restraint and confidence.

Conflicting views

At a recent meeting with students at City University of Hong Kong, filmmaker Ann Hui talked about how she and the screenwriter Li Qiang worked on the script, piecing it together from the reminiscences left by Xiao Hong's contemporaries, including two heavyweights of early 20th-century Chinese literature - Lu Xun (1881-1936) and Ding Ling (1904-1986). Hui said there were conflicting versions of the story and several missing links as well, which they preferred not to tie up.

"When I first read Li Qiang's draft, I felt confused, but in a good way, like what I felt when reading James Joyce's Ulysses," said Hui. "I am still not sure about the result, as different people seem to react differently to this movie."

Indeed, it is possible to read the film as a fragmented and fictionalized re-telling of Xiao Hong's turbulent love lives and also as a documentation of one of the most vibrant periods in China's cultural history - when Communist ideals and its place in literature and the arts were being debated by the most eloquent literary voices in the public domain. The film is narrated documentary-style. A cavalcade of literary figures - Jiang Xijin, Zhang Meilin, Duanmu Hongliang (whom Xiao Hong later married), Zhou Jingwen, Nie Gannu and Luo Binji (who eventually wrote Xiao's biography) - are made to face the camera as they talk about Xiao Hong, revealing a thing or two about the writer's vocation in 1930s China.

Art for art's sake

Xiao Hong went against the tide by dissociating her writing from politics. Xiao Jun, with whom Xiao Hong shared her most intense moments, believed otherwise. His focus was firmly on anti-Japanese literature. Believing he was a soldier first and writer only later, Xiao Jun stayed in northwest Shaanxi province to join the guerrillas, while Xiao Hong went to the relatively safer city, Xi'an. The scene in which they part - she in the train with her soon-to-be husband Duanmu, and he on the railway platform, awash with an unnatural amber light, both trying to act normal - is one of the most heart-breaking scenes in the film.

The film's title is borrowed from a letter Xiao Hong wrote to Xiao Jun when she was temporarily estranged from him and living in Japan. She calls it her "golden era" - safe from the vagaries of living in a politically-volatile China, and yet incarcerated by the boundaries of security that kept her away from Xiao Jun. Ironically, her life with Xiao Jun - heady and passionate as it was - was also a cage in a way, which she never quite managed to step out of. At her wedding to Duanmu, Xiao Jun keeps reappearing in her speech. She never could let go of the man who did not treat her too well.

Contact the writers at basu@chinadailyhk.com and frannie@chinadailyhk.com

|

A terminally-ill Xiao Hong spent her last days in a war-ravaged Hong Kong, in the company of her husband Duanmu Hongliang and biographer Luo Binji. |

|

Xiao Hong's tempestuous love affair with Xiao Jun is one of China's best-known literary romances. Provided to China Daily |

(HK Edition 09/26/2014 page7)