Servants in their own land

Updated: 2014-03-07 07:27

By Li Tao(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Hong Kong's wealth gap has widened potentially to levels that pose a risk of social disruption and while some critics decry latest government efforts to help the working poor in the city's low-paid service industries, others see efforts to narrow the wealth gap as essential to avert a crisis. Li Tao reports.

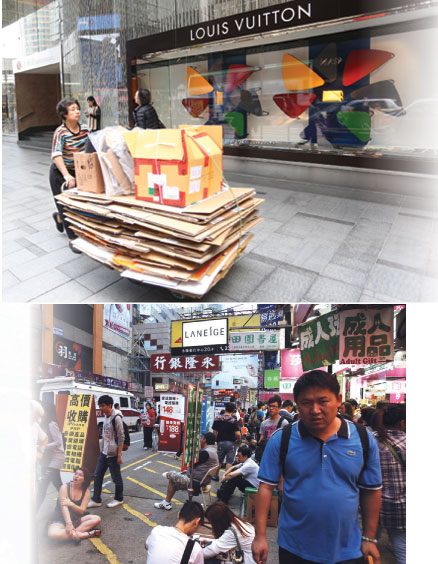

Hong Kong loves to bask in its reputation as one of Asia's most affluent, opulent cities. There are so many millionaires, being poor seems out of fashion. Some of the leading class, allowed cries of alarm to well up in their throats as Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying rose to make his annual policy address during which he announced billions of dollars of expenditures on new programs to help lift the working poor from malnutrition and abject need.

While many proclaimed that the massive increase in social welfare spending would pose a threat to the city's cherished competitive edge, the sad reality is, that the unbalanced economy has come back to haunt the city where one-fifth of the population hover on the edge of destitution.

Hong Kong tallies 1.3 million people living below the poverty line - earning less than half the city's median income after taxes and social welfare. Middle-class earners also find reason to question whether Hong Kong holds a future for them, or whether the economy has tilted so sharply that it 's meant to ensure the rich get richer, while everybody else gets poorer.

No longer is it possible to sweep this blight on the city's reputation under the carpet, since the future prosperity of the SAR is at stake.

Households earning less than 60 percent of the median income now become eligible for a Low-income Working Family Allowance - a new form of financial assistance tied to employment and working hours. Leung offered his assurance, these moves demonstrated the determination of the SAR government to tackling the most deeply rooted problems in our society.

Between 1996 and 2011, family incomes underwent a dramatically polarization said Hong Kong's Census and Statistics Department in its latest household income distribution report released in mid-2012.

During the 15-year period, the proportion of families earning monthly incomes exceeding HK$60,000 ($7,734) surged to 12.2 percent of the population in 2011. In 1996, the percentage was only 6.9 percent. On the other hand, 214,000 families, or 9.1 percent of households earned less than HK$4,000 a month here in Hong Kong in 2011, which compared to 6.7 percent of the total back in 1996.

Hong Kong's Gini coefficient, also known as Gini ratio, that measures the income or wealth inequality among residents of a given area is nearing a crisis stage - above 0.4, at a level creating a potential risk of social unrest. (A Gini coefficient of 0 indicates perfect equality of income. The higher the coefficient, the greater the income disparity). The city's Gini ratio rose to 0.537 in 2011 from 0.525 a decade ago, according to government data released in 2012.

By comparison, the city's income disparity is greater than that of five major developed countries: Canada, the UK, the US, Singapore and Australia. Hong Kong's Gini ratio was the highest, trailing behind Singapore's 0.482 and 0.469 in the US.

In the newly released Mercer 2014 Quality of Living rankings, Hong Kong, one of the most affluent economies per capita in the world, finishing 71st position, far behind its most avid competitor, Singapore, which finished with a much more respectable 25th place in the global ranking.

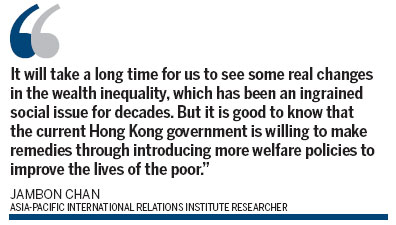

Asia-Pacific International Relations Institute researcher, Jambon Chan argued, in an interview with China Daily, that the destabilizing wealth gap has become a side-effect among several economies caused by market divisions emerging from globalization. The wealth gap, he contends, is not just an issue for Hong Kong but a universal problem.

While each economy gradually found its strengths during the process, Hong Kong, with its industrial manufacturing base having fled to the Chinese mainland over recent decades, the city has become heavily dependent on its only remaining economic strength - services.

Severe wealth disparity

According to a research note by the Hong Kong Trade Development Council (HKTDC) released in January 2014, Hong Kong continues to hold the title as the world's most service-oriented economy, with service sectors accounting for more than 90 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Of the four pillar economic sectors, trading and logistics account for 25.5 percent of GDP in terms of value-added in 2011, while financial services contributed 16.1 percent to the city's overall economy, services to producers 12.4 percent and tourism 4.5 percent.

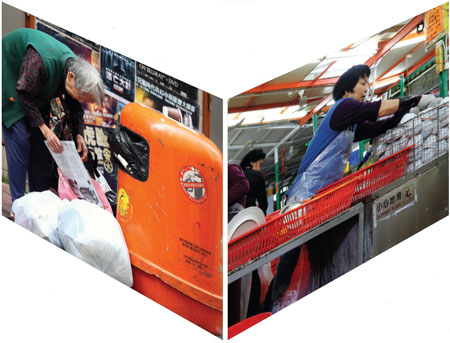

Services-related careers differ substantially from one another. Some require advanced qualifications such as physicians, lawyers and financial professionals. These get more respect and a lot more money. At the other end of the scale are cleaners and dish-washers. People in these jobs expend a lot of energy but don't make much money.

"When the rich are getting even richer, lower-income families are not better-off over the years. We've seen a severe disparity of wealth groups in Hong Kong nowadays," said Chan.

Earlier this year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) issued a warning about the threats posed by income inequality in the world these days, stating bluntly that the widening income and wealth gap poses a threat to global economic growth.

The Managing Director of the IMF, Christine Lagarde, ahead of the World Economic Forum in Davos, in January, declared that the fruits of economic activity in many countries or economies today are not being widely shared, as the benefits of economic growth were being enjoyed by far too few people, which is not a recipe for world's stability and sustainability.

The situation in Hong Kong is even worse because, in an overwhelmingly services dependent economy, the working population tends to become either wealthy or impoverished. With the middle-class base eroded, many people in the city today are unable to make ends meet and they're not happy about it.

In 2013, a misery index created by Shue Yan University's Economic and Wellbeing Project showed that seven of every 10 people in Hong Kong described themselves as "living in misery".

The outcome suggested that people's happiness is in direct proportion to their income. Households with monthly incomes of HK$10,000 to HK$20,000 were the most wretched in the city. Households with a monthly incomes of HK$50,000 or more were the happiest.

Some may argue that Hong Kong people have a higher threshold of "happiness" compared with other place. A global study by the investment firm Royal Skandia in late 2012 found that the average Hong Kong person believes he needs an annual income of HK$1.5 million - or HK$125,000 every month - to be happy.

The cold truth is that only 4.2 percent of the working population in Hong Kong earn more than HK$60,000 a month in 2012, according to government data. The same statistics showed people in the city, on average, were able to earn on average HK$12,800 per month, in late 2011.

Besides the monotonous economic structure, the widening wealth gap in Hong Kong is also due to a combination of many other entrenched factors in the city.

A research journal, titled "Tipping point: Hong Kong's alarming income inequality", released by the Hong Kong Baptist University in 2012, attributes the city's income inequality to a number of longstanding issues, including the influx of unskilled laborers, out of control property prices and surging inflation.

Escalating inflation

Despite the fact that local demand for unskilled workers is huge, salaries have not gone up by much.

In the meantime, Hong Kong's housing prices have soared beyond previous record highs set back in 1997, and have doubled from the record lows of 2008. There is also a widening gap between people who own real estate assets and those who do not, the research report said.

It added that soaring prices in the city also hit the poor hard, with inflation driving up goods and services prices, especially food prices. Poor people are forced to pay an even greater proportion of their meagre incomes on daily necessities, translating to a much harder life.

Certain groups of people in Hong Kong are particularly vulnerable to poverty, particularly those aged 65 and above, children below 14, and youths between 15 and 24.

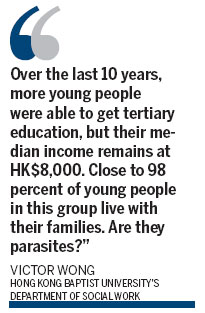

"Over the last 10 years, more young people were able to get tertiary education, but their median income remains at HK$8,000. Close to 98 percent of young people in this group live with their families. Are they parasites? It's tremendously difficult for young people to live in their own apartments," noted Victor Wong of Hong Kong Baptist University's Department of Social Work.

Chief Executive's dedication to help the poor in Hong Kong might not change the fact that wealth gap remains an issue in Hong Kong, but the financial aid initiatives, regardless of local criticisms appears timely and indispensable, Tai Hing Shing, a commentator on social affairs, told China Daily.

"It's a very good start for Leung's government, which have vowed to make a difference (for the people) in a market environment," Tai said.

"Previously, Hong Kong governments used to let the market determine everything, including the widening wealth gap, but it was unable to solve the problems. We all know that inequality is now a serious problem in Hong Kong, therefore, it is necessary for the government to proactively take measures to alleviate the issue," said Tai.

Tai also acknowledged the government's efforts to cool Hong Kong's property market are crucial to stabilizing the rental and home prices to prevent a further appropriation of wealth by the financially well off.

Chan, of the Asia-Pacific International Relations Institute, added that the buoyant commercial rental market in Hong Kong also has hindered developments in the innovation and technology sectors. Many startups can't afford the rents as one of the greatest burdens to opening a business in the city.

"High rental has dragged down the establishment of new industries, greatly, which, in other words, has impeded economic restructuring here in Hong Kong," Chan said.

As the chief executive's new welfare initiatives announced in his policy address will cost another HK$10 billion to HK$20 billion in addition to the city's already massive recurrent expenditures, some people worry that the well-being measures will become a big burden for the government.

However, Chan took exception to those voicing those concerns, saying he believed subsidies for grass-roots, low-income families are essential responses to social inequality.

"It is practical for the government to figure out more ways to boost income rather than consider it as a burden."

"And it will take a long time for us to see some real changes in the wealth inequality, which has been an ingrained social issue for decades. But it is good to know that the current Hong Kong government is willing to make remedies through introducing more welfare policies to improve the lives of the poor," Chan added.

Contact the writer at litao@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 03/07/2014 page5)