Aliens at home

Updated: 2013-09-27 06:59

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

They were born in Hong Kong - but live out of the mainstream - members of ethnic minorities that shun outside influences and remain apart. One man, however, has won wide acclaim for helping to break down cultural barriers. Ming Yeung reports.

For decades, Hong Kong's ethnic minorities have lived pretty much within their familiar circles and have not integrated well with the local Chinese community. It's the language barrier, the lack of communication. Shafi-Asaf-Mohammed took it up as a personal crusade to breach the ethnic barrier and has been so successful, he was invited by Leung Chun-ying to be guest of honor at the chief executive's inauguration ceremony last year.

His family origins go back to Pakistan. Here, they call this third generation Hong Kong resident, "Tak Gor". It means "big brother Tak". He's popular - gets a warm reception wherever he goes. People appreciate the effort he's made, helping newcomers in Tin Shui Wai to integrate and feel at home. Tin Shui Wai is one of the newest satellite towns. There are a lot of mainland emigrants and people of ethnic minorities.

Shafi moved to Tin Heng Estate 12 years ago. He recalls how bad it was, clashes all the time between local Chinese and ethnic minorities. The Chinese complained about the din raised by ethnic kids charging around the playgrounds at all hours. The minority folk pushed right back, charging ethnic discrimination. That's what got Shafi started, becoming a mediator between the contending groups.

"All the quarrels boiled down to lack of communication," says the 46-year-old secondary school teacher. His family are third generation emigrants, rooted to their service in the British Army. Shafi's grandfather was deployed to Hong Kong in the 1960s under a colonial government that considered learning Chinese not very important.

The family put high value on education. Shafi went as far as form two at an international school in Hong Kong, then continued his studies in Scotland. He spoke English and French but was barely functional in Cantonese in those days.

Shafi, gifted with a kind heart, enrolled in medical school. But instead of studying, he played tennis and there went med school. Instead, he got his MSc in Chemistry, picked up an MBA on the fly, and came home to Hong Kong.

The local community thought poorly of dark-skinned people then. Shafi has vivid memories of being humiliated on public transport.

"I got on a bus. Wearing a suit. Sat next to a Chinese man. He got up immediately and stood far away from me. He preferred standing to sitting next to me!"Shafi recalled with a note of anger.

"I yelled at him, 'What's the matter with you? Do I owe you money or something?' The man pretended he didn't hear me and looked somewhere else."

Learning Chinese

After Shafi came back to Hong Kong in 1990, learning Chinese seemed more important than ever. "You could barely survive without knowing Cantonese," he says. It was still years before Hong Kong's scheduled return to the motherland, but Shafi caught the urgency. "Why not? It's better to start now," he recalls thinking at the time.

He worked hard - having no Cantonese tutor - started learning with the help of a famous Japanese anime figure - Robocon, the corpulent, shiny, red robot screw-up that was scared of cockroaches.

"I still remember clearly the lyrics of its song," he laughs, humming the first few lines. "People in Cantonese soap operas talk too fast. The cartoon animation is slow and uses a simple vocabulary."

Shafi was pretty much alone in his community as far as his studies went - not isolated or anything. Fellow members of the local Pakistani community just didn't think like he did. "They were traditional. They had their own clan here and didn't want to change a thing."

Shafi kept going. "I took the kids myself to look for schools and go through all the procedures," he says. People started responding one by one.

Shafi sets an example for his local community today. Every Saturday, in his role as chairman of his building's Mutual Aid Committee (MAC) he spends time with old folks, to go yum-cha, listening to their problems. He is the first non-Chinese MAC chairman in Hong Kong and he's held that post for nine years.

Some have come to agree with Shafi. He's seen them change gradually. Others in his community are offended by him. They consider what he's doing offensive. "They've told me to mind my own business. They isolate themselves. They don't let their kids out. They don't let outsiders in. In the long run, it doesn't work," he comments. "They will regret it in the future but by then, it will be too late."

Gradual integration

He thinks it'll take a couple of generations before there's full integration, and of the hold outs he says, "Their descendents are Hong Kong passport holders, locals. They will even have given themselves Chinese names."

An old man said to him, "Hey Tak Chai (little Tak), you're no longer superior. You have two apprentices now." The old man was referring to Nabela Qoser, Hong Kong's first non-Chinese reporter who works for a Chinese news platform, and Heina Rizwan Mohammad, the city's first South Asian woman recruited as a police officer.

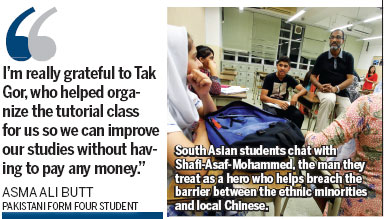

Asma Ali Butt is a Pakistani girl with high hopes of becoming a History teacher. The Form Four student and about 10 other South Asian girls who live near Shaji attend government-funded tutorials for one hour, three nights a week.

Asma was born in Hong Kong and attended a Chinese primary school, but sh'es not at all satisfied with her proficiency in Chinese. The girl will sit for GCE (General Certificate of Education) exam, instead of the local university entrance exam (DSE).

"Not knowing Chinese will make the future more difficult. Even if I can get into a local university, I won't be able to get a decent job when I graduate," she says, wishing she could live up to her family's high hopes for her.

"I'm really grateful to Tak Gor, who helped organize the tutorials for us so we can improve our studies without having to pay any money. "

"I'm really proud of the girls. They studied hard to have a better life. They got into different professions, and they're ready to serve their society," says Shafi.

His outlook on the boys from his community is pretty bleak, though. "Instead of blending in with society, the boys blend in with the triads," he sighs.

As the first member of an ethnic minority to sit on the District Fight Crime Committee, Shafi has worked with different government departments to slow down the spread of drugs among youth in the community.

"It hurts me to see (these young people) skip school and commit crimes and end up in prison," Shafi says, lowering his voice. "It's not them I pity, but the parents who raised them and who hoped their sons would go to school. But they (the boys) gave it all up because of a few thousand bucks to buy drugs."

The boys' families are normally impoverished, Shafi acknowledges, so the young people go off in the wrong direction, want to buy things they can't afford, and start looking for the fast way to make a dollar.

The man with so much community spirit cares, not only for the general welfare but for those in need. He's recruiting volunteers from the Chinese University of Hong Kong to help new immigrant children keep up with their school work.

These days, when bullying and racism surface, Shafi still feels the pain. The same thoughts go through his mind over and over. "We are all humans. When things like that happen, you either hurt people's feelings or the other way round, we all feel bad.

"No matter what, fostering cross-cultural inclusion is always my goal. I hope one day, ethnic minorities will be able to repay society."

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

|

Shafi encourages his fellow countrymen to let their kids study in mainstream schools to learn Chinese. But he knows it'll take a couple of generations before there's full integration. |

(HK Edition 09/27/2013 page2)