Struggling to make the grade

Updated: 2013-08-30 07:42

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Hong Kong continues to turn away thousands of students every year from its overcrowded universities. This year, fewer than half of those who met the qualifications for admission found places. It's a problem many see as a threat to Hong Kong's future position in Asia. Ming Yeung reports.

It has been more than four weeks since Candace Li got the results of her Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) examination - the one that decides whether you're going to be a success in life, with your position at a Hong Kong university guaranteed, or whether life is about to get a lot tougher. Li's marks, for example, read like a death sentence as far as she was concerned. Her memories of the chill that ran down her back, standing in shock staring at the piece of paper in her hand, are quite vivid.

Her exam results met only the basic requirement for a local university. On Hong Kong's 7-point grading system (7 being the highest), Li scored 3 in Chinese, (minimum for university admission, 3); English, 4 (minimum, 3); Mathematics, 4 (minimum, 2); Liberal Studies, 4 (minimum, 2). In her electives, Li scored 4 in History and Geography (minimum standards, 2) each. Her top five marks gave her an aggregate score of 17.

And here the grim reality of education in Hong Kong begins to reveal its nasty visage. Seventy thousand students wrote that exam. Twenty-eight thousand met the minimum standard for university admission but publicly funded universities don't have that many places - only 13,000 (another 2,000 or so places are given to students who do not sit the local public exam but are admitted by universities on the basis of individual requirements).

Left out in the cold

Ten thousand students got aggregate scores of 22. Li, with her 17, was going to get trampled in the stampede if she even thought about applying. "I knew I wasn't a top student but this marginal result left me out in the cold. I passed the basic requirement but wouldn't be able to go to any college here," said Li.

Li was in the same quandary as roughly 15,000 other students - qualified but not qualified enough for a local university.

Hong Kong's government is forever criticized for failing to provide an adequate number of undergraduate places. It's even been accused outright of clinging to the antediluvian view that education is for the rich, or some other elitist standard. But compared to other developed economies, Hong Kong doesn't stack up. Here's the truth of it, Hong Kong admits only 18 percent of its student population to public colleges versus 30 percent on average in the OECD's (the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) 34 members.

What does it mean? It means Hong Kong is building an education deficit. It means fewer people in Hong Kong, on a percentage basis, get to attend public universities than in other developed economies.

Education sector lawmaker Ip Kin-yuen charged that the government has failed to meet expectations of parents and of society as a whole. "Hong Kong has no natural resources but only human capital. Without sufficient cohorts of high-end professionals to support the city's transformation into a knowledge-based economy, we will lag far behind our counterparts."

Tung Chee-hwa, Hong Kong's first chief executive, vowed back in 2000 to increase tertiary school graduates to 60 percent. Tung's successor, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, even talked about transforming Hong Kong into "an education hub".

The reality doesn't even come close to the lofty goals. In Hong Kong, public spending on education accounted for 3.8 percent of GDP in 2012/13, two percent below the average among OECS's economies.

OECD data reinforces the point that developed countries spending the greatest proportion on education as a percentage of GDP tend to have higher percentages of college graduates.

Wider gap seen

The data shows college graduation rates climbing in developed countries while Hong Kong's are relatively stagnant, threatening to leave the city behind in the proverbial dust.

"I'm afraid the gap will get wider if the government doesn't invest more in education. This will cause Hong Kong to lose its competitive edge," Ip said. "Failing to provide more places in public universities, Hong Kong will never see itself become a truly knowledge-based economy capable of competing against the best."

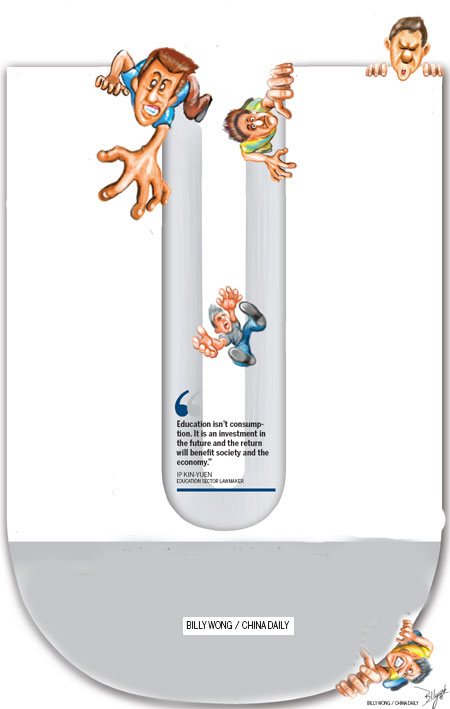

"Education isn't consumption. It is an investment in the future and the return will benefit society and the economy," Ip said.

What hinders development of higher education in Hong Kong, Ip observes, isn't the land shortage or any other physical constraint. It's the lack of a long-term vision from the people who run the system.

Following Tung's declaration on higher education, private schools started offering self-funded programs. There have been more alternative study paths available in addition to the associate degrees: vocational training, higher diplomas, distance learning that charge up to HK$100,000 a year.

Last year, students who didn't make the grade had a choice of 140 associate degree programs and 175 offering higher diplomas. There were 97 self-financed degree courses run by university continuing education departments and 120 degree top-up programs, most of those offered by overseas institutions.

The government only did little to meet its policy objectives. The commitment to higher education has increased only marginally since 2012 from 14,500 to 15,150 places per year.

There are too many restrictions facing Hong Kong kids who want to complete their post-secondary education.

Ng Po-shing, vice director of Hok Yau Club's Student Guidance Centre, summed all that up: the self-financed courses are too expensive and the choices too narrow. "The choices are either business- or arts-based, because the cost of running them is cheaper and the schools are confident they can attract enough students."

Ng calls on the government to provide another 2,000-3,000 publicly funded places, in high-technology, engineering or nursing courses where there are major shortages in the city's talent pool.

Professor Joshua Mok Ka-ho, acting vice president (research and development) and associate vice president (research and international exchange) of the Hong Kong Institute of Education, said the government isn't doing too badly. While education spending accounts for less than 4 percent of GDP it does account for more than 20 percent of public expenditures, when pressing issues like the aging population and the massive shortage of housing still confront the people.

"The employment pressure arising from expansion of universities is not simply a social problem, it's a political problem. From Taiwan's lesson, we know the key to improving higher education development is diversity, not quantity," Mok stressed.

Lawmaker Ip Kin-yuen disagrees. He says Hong Kong has plenty of room for improvement just by giving more needy students a hand on the path to higher education.

"If a three-year-old has to worry about what sickness he will suffer when he turns 80, he is unduly concerned," Ip said.

Mok said private institutions have taken a huge role in contributing to the high college student enrollments in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. He worries that Hong Kong will have a mismatch of talent to job openings like Taiwan, where there are too many jobless college graduates on the street while the city is suffering a "brain drain". With more than 160 universities, public and private, on the island, Taiwan is having a problem of admitting enough students.

"The question of how many more publicly funded places should be added rests with Hong Kong's new industries and whether they can produce enough jobs for our future degree holders. It's not simply a matter of fulfilling parents' and students' expectations," Mok said. He was referring to the so-called six new economic pillars identified by the previous administration. They're economic areas where Hong Kong was perceived to have an advantage: medical services, cultural and creative, innovation and, surprisingly, education.

For all the roadblocks and frustrations, the city's high school graduates remain passionate in their pursuit of higher education, says the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups, based on a survey in June. Of the 583 DSE students interviewed, 78 percent said that if they didn't get into to one of the public universities, they'd look for higher education opportunities somewhere else. Only five percent said they would give up and get a job.

Finding no room for her at a Hong Kong university, Candace Li gave up her dream of attending university here and enrolled at a Taiwan university.

She's taken in stride what she perceives as her failure and has moved on. "Like it or not, I will work hard to get my bachelor degree. This is all I can do to repay my parents," she said.

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 08/30/2013 page1)