The kids they left behind

Updated: 2013-08-23 08:10

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Families, separated a decade or more by the boundary separating Hong Kong and the mainland, are slowly coming back together under rules enacted in 2011 to speed up reunification. But even as those bonds are renewed, there is a new generation of loved ones being left behind. Ming Yeung writes.

At 8:10pm, nearly every day of the week, Sharon Pang, looking a bit younger than her 36 years, arrives home in Ap Lei Chau, Aberdeen. She is exhausted after her day's work, but her spirits are high: her son, parents, elder brother and younger sister await her arrival.

To Pang, this is supreme happiness, and a happiness denied her until last June when she was granted, at last, her one-way permit, allowing her to be reunited with her family in Hong Kong.

"Change your clothes and come and eat," her mother insists, indicating the feast that awaits: steamed fish, chicken, and two kinds of vegetables. The pleasing aroma fills the room. "I've already eaten," Pang replies, smiling. Her mother knows what Pang means. She's on a diet.

Pang and her elder brother fall into that category of "over-age children". The formula that defines the group is a bit complex. They had to be under 14 prior to November 2001 when their natural fathers or mothers were granted Hong Kong identity cards. The kids, however, were not granted residency at the same time as their parents - and separately had to apply for one-way permits to reside in Hong Kong. If, however, the kids came to their 14th birthday before that permit was approved - it was all over. Their applications were automatically suspended. They were left more or less permanently separated from their parents.

Pang's father came to Hong Kong alone and penniless in 1978, leaving his family behind in Sihui in west-central Guangdong province. In 1993, her mother was allowed to migrate to Hong Kong, bringing only an 11-year-old daughter.

Festival reunion

Until last year, Pang had been allowed to see her family only at festival times. Being of an easy-going, almost happy-go-lucky personality, Pang took it all in stride, never daring to dream that one day she could actually settle permanently in Hong Kong.

Circumstances presented plenty of reasons to quell her optimism. Legal battles erupted between over-age children and the Hong Kong government in 1999. The abandoned children went to court, challenging the head of immigration over their right of abode in Hong Kong.

The landmark judgment in the case of Chan Kam-nga vs the Director of Immigration was brought down in January 1999. The Court of Final Appeal held that children acquire the legal right of abode in Hong Kong under the Basic Law if at least one parent was a permanent resident of Hong Kong, whether that legal residency was established at the time the children were born or at a later date.

The Hong Kong government estimated the potential number of over-age children affected by the ruling to be greater than 1.6 million. Fearing a deluge of migrants, the government handed the case to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPC) for an interpretation of the relevant part of the Basic Law.

The NPC issued an interpretation favorable to the government's position. It stated that over-age children had no legal right of abode in Hong Kong unless one or both parents were permanent residents here when the children were born. The judgment of the Court of Final Appeal, thus, was overturned and the number of eligible applicants fell to less than 300,000.

Pang fell outside the scope of the ruling. "I was disappointed. I was young and single, and my parents were here. Of course I wanted to live with them," said Pang, recalling her anguish.

Her dream to be reunited with her family was re-ignited when the central government ruled that beginning April 1, 2011, mainland over-age children of Hong Kong residents may apply for one-way permits to come to Hong Kong if their parents had acquired Hong Kong identity cards while the children were under 14, up to November 1, 2001. Over-age children were allowed to enter in phases.

"At present, it is the third phase in which the mainland authorities are accepting applications from mainland residents whose natural fathers or mothers obtained their first Hong Kong identity cards before 1982," says a Security Bureau spokesman.

According to the mainland authorities, as at end of June, some 43,000 OWP applications had been received from over-age children. With most of the applications reviewed, 31,000 (72 percent) had been approved for one-way permits.

Pang's life on the mainland had been rather insipid during the years she had to wait. She graduated from high school, had a few casual jobs and married a civil servant in 2005. She got pregnant a year later, and planned to have the baby in Hong Kong, purely due to the mainland's one-child policy.

"My husband was a civil servant and not allowed to have a second child. To play safe, if I wanted a second child, I could do that only if my first child wasn't born on the mainland," she told China Daily.

"I trust Hong Kong's education. However, the living standard here is far below the mainland's," says Pang, who now shares a 300-something-square-foot flat in public housing with her son and four family members. Being reunited with her parents came at a cost. Pang now has to deal with separation from her husband.

She has to live in the city for four years before her spouse can settle here. Her son, who has been promoted to primary two, cries every time he has to say goodbye to his father. During his summer vacation, he is in Sihui with his father. "I don't understand why the Hong Kong government has to keep family members apart. Some people are newly-weds and can't spend several years alone," Pang argues.

Whether or not her husband ever will come has yet to be decided. "It depends on my son's will," Pang says. "If he wants to go back to the mainland when he gets older, it is fine with me."

Although the wait will be long and painful, there is still hope for Pang. In four years from now, her family will be fully reunited, either in the SAR or on the mainland.

Flora Zhou faces a much more difficult situation. She settled in Hong Kong last year under the policy that accepted her as an over-age child. But her only son is 20 - and under the existing policy he also is an over-age child. He won't be able to come to Hong Kong until she retires.

Right-of-abode fighter

Zhou, now in her 40s, was a frontline fighter for her right of abode in Hong Kong in 1999. Her other four siblings, except her youngest brother, were all over-age children. They were left by their father in Panyu, a district of Guangzhou in Guangdong province.

Zhou's father came to Hong Kong in 1978. His search for a better life opened few doors. He found a job as a construction laborer. He lived in a subdivided flat in Tai Kok Tsui. He was ashamed of his living conditions and refused to let his wife and children come to live with him. When he broke his leg in an industrial accident in 1993, Zhou's mother came to live with him, bringing their youngest son.

Soon after, her second youngest sister, who had just graduated from a mainland university, insisted she wanted to come to Hong Kong in 1997. She was granted her identity card.

Finding new hope in the court ruling of January 1999, Zhou's mother persuaded her to come - on travel permits - with her siblings. Zhou's husband was a gambler. She wanted to get away from him. She abandoned her hair dressing salon and came to Hong Kong, leaving behind her only son, who was in primary school.

Since her arrival, she's had a letter from her son, begging her to let him come and live with her. The boy complained his father treated him badly. But Zhou had to say no, telling the boy it would be impossible now - but perhaps someday

The applications submitted by Zhou and her siblings were rejected. They did not meet the requirements according to the strict interpretation of the Basic Law by the central government.

Zhou refused to give up. She was determined to fight for her rights. She stayed on illegally when her travel permit expired.

There were many supporters locally on her side, and many more who had shared the rejection of their applications by Hong Kong authorities.

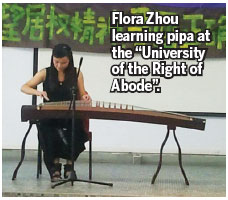

The Society for Community Organization and the Justice and Peace Commission of the Hong Kong Catholic Diocese joined the suit on behalf of over-age children. They helped to fortify this marginalized group and encouraged the mainlanders to continue fighting. To gather the scattered people who had been hiding in their homes, the so-called "University of the Right of Abode" was established.

Zhou was learning English a word a day, and she'd taken up a new hobby - pipa, the four-stringed Chinese musical instrument. She became a pupil of a well-meaning pipa musician, who agreed to teach her for free. Zhou enjoyed the classes. Over years of intensive training, Zhou, step by step, achieved the ninth grade.

She was beset by fears of being apprehended and at times became extra vigilant when police tightened patrols looking for those who had over-stayed.

One morning, when Zhou was going to the market to buy vegetables, she bumped into several police officers in an elevator. She panicked when was asked to show her identity card. She was arrested and locked up at Tsz Wan Shan police station.

The Italian priest, Franco Mella, who became a cult hero fighting for the right of separated families to be reunited, arrived at the police station soon after to request that Zhou be set free.

In the meantime, her parents also arrived. "Free Zhou! Free our children! They are innocent!" Zhou remembers the father and other supporters shouting outside the police station. She remembers the sound of her mother crying. The memory of that day still brings tears to Zhou's eyes.

"There were so many strangers, some even on hunger strikes, who came to support us. I was deeply moved."

Despite the pleas made on her behalf, Zhou was deported to the mainland. Thereafter, her visits to Hong Kong were governed by three-month travel permits.

Zhou was granted her one way permit last year.

Zhou got her wish but the sacrifice she made was heavy. During the years of separation, she lost track of how her son had grown.

"One time, I bought him a pair of sneakers and sent them over with a friend of mine. My son called and asked me who the shoes were for. I said, 'They are for you, of course.' He said, 'Mom, they are too small,'" recalls Zhou. "As a mother, I even didn't know how big my son had got."

"I didn't regret coming to Hong Kong. Only by coming here could I divorce my husband," she says. "I'm very grateful that I have an understanding son."

Contact the writer at mingyeung@chinadailyhk.com

(HK Edition 08/23/2013 page2)