In search of the lost culture

Updated: 2013-04-05 06:53

By Doug Meigs(China Daily)

|

|||||||

|

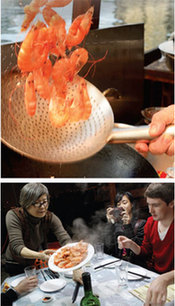

A historian at the Chinese University of Hong Kong says that the lavish meals at Shun Kee differ from what boat people used to sell in the typhoon shelter. Leung Hoi says he is combining traditional typhoon shelter cuisine with cooking skills learnt on land. Doug Meigs / China Daily |

Hong Kong's Causeway Bay typhoon shelter once was a thriving nighttime entertainment district, where people escaped from the summer's blistering heat. Some former residents of the shelter hope to bring back that culture, Doug Meigs reports.

It's around sunset. An old woman on Nam Kee Wharf shouts to a water taxi festooned with pink neon lights. The boat putters over. The evening's first dinner guests have arrived. They climb aboard the water taxi and are ferried the short distance to a cluster of small wooden "dinner" boats, loosely distributed around a large floating kitchen.

Welcome to Shun Kee, the only floating restaurant in today's historic Causeway Bay Typhoon Shelter. Flames erupt into the night air bearing tantalizing nostalgic aromas of a culture lost for nearly two decades. Chef Leung Hoi, 48, at work on the kitchen boat, waves to arriving guests then tosses fresh shrimp into a wok.

Each boat is set banquet style, floating amidst ragged sampans and modern yachts, a scene of nearly picture-perfect tranquility. Tonight's menu features typhoon shelter crab.

"The typhoon shelter food culture is a traditional culinary culture. I grew up in it and want to promote the food. Many restaurants on land claim to sell typhoon style, with cooking skills not half as good as in the past."

Leung grew up in the shelter, so did his brothers and sisters. They come from a family of indigenous "boat people," whose roots go back generations, long before the colonial era.

Bobbing in the water beneath Hong Kong's glowing skyline, Shun Kee evokes memories of bygone days.

Hollywood 's classic depiction of Hong Kong in the 1960 film, The World of Suzie Wong, captures the atmosphere of the once-impoverished area before it became a kitschy destination for people seeking a night snack. As Hong Kong became more affluent, boat dwellers seized the opportunity to improve their livelihood, situated conveniently beside the emerging high-rent residences and Causeway Bay luxury shops.

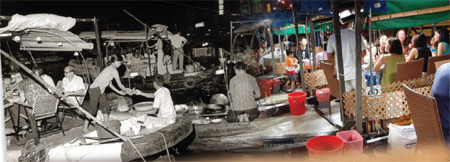

The way it was

More than 300 boats once crowded the shelter. It was a floating village of dazzling lamps after nightfall. Sampan cruises were popular, offering tours of the area. Passengers would munch on noodles, congee, pan fried scallops, and-the shelter's most iconic-typhoon shelter fried crab. Some boats sold cigarettes, fruit or beer. Other boats carried Cantonese Opera singers. Before the days of air-conditioning, the shelter's cool harbor breeze provided relief from sweltering summer nights.

City folk were fascinated by the lifestyle of the typhoon shelter people, says Chinese University of Hong Kong history professor Ho Pui-yin. She remembers visiting the shelter as a child: "I went with my family and sometimes when friends came to Hong Kong. We showed them how the boat people lived and took them to the shelter for a bowl of rice soup or to hear Cantonese songs."

She remembers a carnival atmosphere of boats decorated with lanterns: "the most magnificent reds, yellows, and pinks." Floating musicians and vocalists would take requests. Ho remembers feeling swept up in the atmosphere as she sat enjoying an order of tang tsai jok (Cantonese for "little boat congee") full of assorted bits of seafood and pork.

Chef Leung recalls a convivial, community atmosphere. Shun Kee's full dinner spread differs from what visitors would have found at the typhoon shelter in past decades, he says. During their youth, Leung and his brothers each specialized in a different delicacy. His eldest brother operated a dessert boat. Another sold congee and noodles. Leung's specialty was fried crab. An aunt chauffeured tourists around on a sampan. There were 20 to 30 different vendors in the typhoon shelter, selling food, drinks or flowers. Leung says there was always an "uncle" or "auntie" nearby who had anything the customer wanted.

"Why start over again?" asks Leung, who wears a white chef's tunic, formal garb he adopted during decades of cooking on land. "We used to live here. We grew up on the water. We are boat people."

Some of his employees were neighbors during his childhood, Leung remarks, as he returns to his wok. The aroma of chopped garlic pervades Leung's kitchen; it wafts from plates held aloft by waiters, scurrying over wales and decks, straight from wok to table. A pile of shrimp, massive razor clams, groupers heaped in a deep-fried crispy pile, and scallops topped with vermicelli (and more garlic) are brought in succession. There's a plate of vegetables, then congee, the noodles, then come mollusks, squid, and spicy clams drenched in savory sauce. When the crab finally arrives, it's buried in fried garlic and fermented soybeans. Steaming shells crack, revealing white flesh in all its succulence.

|

Diners must make reservations in advance for a full course meal prepared at the discretion of Shun Kee's staff. Doug Meigs / China Daily |

Non-fragrant harbor

The fragrance of the harbor itself, however, began to take on an undesirable pungency in past decades as the waters became more polluted. "When you took the boat trip, you could smell the bad smell of the harbor," professor Ho recalls, explaining that wind would pick up odors from sewage and spoil the atmosphere.

Ordinances began requiring that every vendor needed a license, every boat had to have a toilet. Relocation schemes helped families to move ashore. "If you gave up your boat, the government would give you an apartment in a public housing estate." Leung says his mother made the trade-off and is living in Fanling with his elder sister.

By 1989, the typhoon shelter was losing its allure. The Leung brothers moved ashore to cook at a nightclub. Then they moved on to work for restaurants around Hong Kong and the mainland. The last of the food boats shut down nearly two decades ago, in 1995. The remnants of the culture moved ashore.

Professor Ho insists contemporary restaurateurs selling "typhoon shelter crab" aren't true to the culinary traditions of the boat people. "In the 19th century, the boat people would think about how to earn more money. If they could sell some seafood or snacks, they were happy. But in the '50s it became more commercial. People would hang out lanterns to attract clients. They would cook different foods that people on land liked."

Typhoon shelter crab, the iconic dish from the shelters, emerged as boat people responded to the appetites of Hong Kong 's nouveau riche, claims the history professor. "The tradition we experienced is gone, I'm sad to say. What we see nowadays is not what we had before. The food you eat now, big crabs and lots of spicy crabs - is not the sort of thing we had before."

She believes the famous "typhoon shelter crab" is derived from Singapore's black pepper crab: "In the '60s or the '70s, we did not have those really big crabs. We had shrimps, cuttlefish and small things, but the big crabs or fish would have gone to restaurants".

The professor says that Hong Kong's floating restaurants emerged as boat people needed more space, so expanded into more lavish ships, like the Jumbo Kingdom and Tai Pak. operating today in Aberdeen Harbour on the southern side of Hong Kong Island. Those two floating restaurants, in addition to the (Man Kim, Man On and Man Lok) harbor cruise/dining ships that berth at the North Point Ferry Pier, are the only licensed floating restaurants in Hong Kong.

Ho has written about the shelter in two books: Challenges for an evolving city: 160 years of port and land development in Hong Kong, and Weathering the storm: Hong Kong observatory and social development.

The much shrunken Causeway Bay Typhoon Shelter seems long past its former glory. All of Victoria Park sits on land reclaimed from the shelter, nowadays dominated by the posh vessels of the Royal Yacht Club. The typhoon shelter was the first built by the colonial government, completed in 1883 after a catastrophic typhoon wrought havoc on the boat-dwelling population 10 years earlier.

Census Department data for the "marine population" in Hong Kong waters shows a steady decline from 136,802 boat people in 1961, to 1,188 as of 2011.

As dinner draws to its conclusion, a middle-aged waitress clears the table on one boat. It's time for the dinner party to depart. The woman unties the boat, dips a long oar into the water, and paddles the boat to shore. In a few moments the entire party is back on land, disembarking beneath the glare of street lamps towering above the Island Eastern Corridor's western confluence. Traffic rushes past on the road that was reclaimed from the watery domain of Causeway Bay's boat people.

Today, the water quality is gradually improving. Only a few people still live on boats near Shun Kee. They can be seen at night, like passing shades of a forgotten era. An old man paddles back to his floating shack. A barking dog heralds his homecoming.

(China Daily 04/05/2013 page3)