Learning to care

Updated: 2013-01-10 06:14

By Andrea Deng(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

A growing number of ordinary people are coming together regularly to give out food as well as to care for the city's underprivileged. Their stories, spreading online, appeal to more to show care for society. Photo Provided to China Daily |

Hong Kong's streets are crowded with people in need, yet for more of us, observing those people in their plight is part of everyday living ... there are some in our community who have made special efforts to open their eyes and meet the people who once went unnoticed. Andrea Deng reports.

Eva Mak was so nervous about handing out 1,000 mooncake pieces to complete strangers that the very thought made her giggle. She'd never done anything like this before.

It was during the Mid-Autumn Festival and the bakery training center where she worked at had enough leftover ingredients to make 1,000 mooncakes to hand out to elderly people.

Plan A was to give the mooncakes to a seniors' care home. When that fell a day before the festival began, Mak put up a message on Facebook hoping to find someone to take the mooncakes off her hands. Her replies led her to Benson Tsang, who suggested she share all the mooncakes with people in Sham Shui Po.

"I thought I was done after moving all the mooncakes to a roasted pork restaurant (where people could pick up the mooncakes). But when Benson asked me if I was free to help them give out the mooncakes, I was petrified," said Mak.

"I've never done this before. I've never known anyone in the neighborhood," she continued. "I didn't know how people will react, whether they would accept the mooncakes, or whether they would swarm in and surround us. I didn't know how to do this."

Mak looked at Tsang and another three helpers, who were already engaging passersby. "Happy Mid-Autumn Festival" "Free mooncakes" they chanted. It took them only 20 minutes to give away all 1,000 pieces.

"We gave each of them two pieces of mooncakes. People dragging cardboard they had collected came to us. There were people wearing aprons, probably fishmongers. There were elders who seemed to be standing idle on the street. They were so happy to have the free mooncakes," Mak recalled.

That was the starting point for Mak to learn to care for needy people, though they are strangers to her. She began noticing more and more stories posted on Facebook telling about people sharing food and life's necessities with the homeless, of chatting with elderly grannies, and getting to know these people who eked out their daily living by gathering bits of abandoned cardboard.

Only then, did Mak begin to take notice of one of her neighbors - a granny who, like many others, collected cardboards on the back streets to earn money.

"I saw this granny every day for a couple of years but I never talked to her. People told me that she was actually wealthy and owned a property," said Mak. She started to talk to the granny, sometimes buying her breakfast.

As it turned out, the elderly lady was not at all wealthy. She owned a house but nothing else and lived on the HK$1,300 old age allowance. But after she paid all her bills and everything she was destitute, and so collected cardboard to make ends meet. Sometimes, the granny told her, three cartloads of cardboard would provide no more than an HK$30 income.

Mak tried to care more about her neighbor, asking whether she was able to keep warm during the chill nights of winter, sharing the cakes that she made. Mak widened her sphere of acquaintances, meeting with more elders and even homeless people.

"I used to think that when people became homeless, it was their own fault. I thought they must be drug abusers and did not deserve compassion. I saw elders on the street picking cardboard and didn't feel a thing, I felt it was normal. Now I cannot believe how indifferent I was and how absurd that was. There was no human caring in the community," said Mak.

Mak becomes one of a group of ordinary people in Hong Kong who claim to "having the eyes of their heart opened" toward current social issues, poverty and the underprivileged - strangers who need not only physical help but sincere caring, the kind a friend or family member would give without condescension.

The Equal Share Movement is the name of one group, whose members get together every month, raising money to buy simple food - roasted pork lunch boxes, fruit, bread or cans of food from little mom-and-pop grocery stores. They also collect second-hand clothes as well as superfluous coupons for bakery stores and supermarkets, and share them with people in need.

A recent Equal Share Movement in late December saw more than 100 ordinary people voluntarily come together in Sham Shui Po, giving out food to around 350 people in the neighborhood. Many of the recipients were elderly, homeless people, retired or unemployed.

What's equally important is that members of the group chat with the underprivileged people and getting to know them. They sit and talk as equals, with the homeless people. The discussions are about casual tops. The most common topic concerned complaints about the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department staffers who try to drive them away. The group members try to avoid asking personal questions, at least until they've had the chance to build up trust.

Group members share stories on their Facebook page, about their encounters with the elders who subsist on old age allowance and recycling cardboard - lonely elders whose sons or daughters rarely visit, they earn meager incomes as cleaners, while some simply are homeless, living beneath an overpass.

Group members have picked up some unusual practices along the way - many always carry a bit of bread or an extra scarf, in case they meet someone on the street in need.

The stories they share, usually are sad ones. There was an 80-year-old who tried to commit suicide, because he couldn't bear the feelings of loneliness he had. A granny who didn't have a phone came down to the street every day, waiting for her niece, who didn't make an appearance again for more than a couple of months. There was the homeless person who finally found a cheap rental apartment but was forced back out on the street right away, because of the bed bugs that appeared on his bed every night. Another story was told about one old couple, who went together to collect cardboard. The husband, wheelchair bound, was pushed to the ground by a staff member of the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department and had to be hospitalized for a month. His wife had to carry on collecting the cardboard on her own.

Many stories such as these are shared, every day on Facebook. People read the stories are touched by them and joined the circle of those who want to help. At every new Equal Share Movement, about 80 percent of those who turn out are participating for the first time. The number of participants has been steadily growing since the movement's inception about two years ago. There were only about a dozen the first time. At the Mid-Autumn Festival in 2011 about 50 turned out, with the number swelling to about 100 at Christmas of that year. There are between 120 and 160 participants for each outing today, with the number reaching over 200 at Mid-Autumn Festival in 2012.

Benson Tsang, who initiated the movement, said it is a moderate protest against the government's failure to deliver an effective social welfare policy.

"There are two question marks: why is it necessary for ordinary people to come forth and give away food, and why are there so many people coming out to ask for food?" said Tsang.

There is no general outcry to resolve the poverty issue or any other social ills, says Tsang. But the tacit, underlying meaning of the protest applies at every occasion, Tsang said.

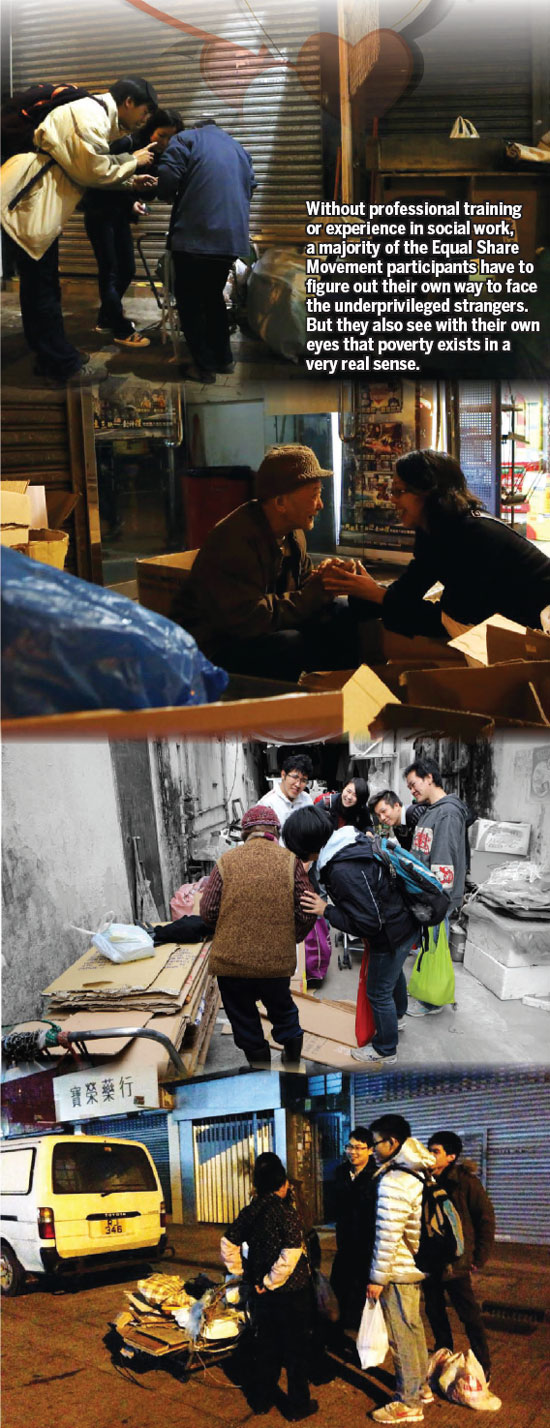

The fact that a large majority of the participants have no professional training of social work or experience encourages them to face the underprivileged outright. Aside from some of the rules and suggestions provided by the core members of the movement, participants basically have to figure out for themselves the way to talk to strangers who may have very different life experience and social backgrounds. Some had a difficult time communicating through their own sense of alienation, which has become a common condition of modern communities. But they see with their eyes that the problems exist in a very real sense.

It is very different from working from the perspective of an NGO, said Jordi Tsang Sing-cheung, an experienced social worker in North District who joined the movement. He said that a social worker is sometimes limited by the framework within which they are working. They could be overwhelmingly driven by goals and the results. They care about whether people know about their good deeds. Having responsibility to account for funding may lead to a lot of time consuming bureaucratic procedures. These are departures from the real mission, which is to care for people in need, said Tsang, and sometimes it is just as simple as chatting with them so that they don't feel bored or lonely.

The Equal Share Movement works in many ways that are different from NGOs', according to Benson Tsang. The participants could feel free to join and donate, or feel free to not donate or not join the movement next time. There is no stable fund raising, with each event having a separate fund raising goal. The group doesn't maintain an ongoing fund. There is no strict, organized structure for the movement, so the group will dispatch funds to people in need when the funds are needed.

While an NGO usually finds it difficult to raise funds and find volunteers, Benson Tsang never worries about not being able to find people to participate in the Equal Share Movement.

Chan Lai-fun, one of the founders and current chairwoman of Sowergift, a similar movement that cares for not just poor people, but also for those who feel less empowered and are disenfranchised in society. These people often are new immigrants or members of ethnic minorities. Chan believes non-organized ordinary people can achieve a lot that NGOs have loverlooked.

"There are many organizations in Hong Kong providing physical help to the people in need, but rarely is there any that purely shows care for other people," said Chan. The 24-year-old financial consultant has been cooking sweet soup and delivering it to elders in Tai Po every Saturday since Christmas Day, 2010. She said the reason why she did so was not intentionally giving out food, and to put more focus on caring while sharing sweet soup or cookies with a granny.

And while stories are shared on facebook, it can be most impactful in the eyes of their friends.

"I believe that to make a society change cannot just rely on one or two volunteers. But their stories could have a tremendous influence on other people," said Chan.

(HK Edition 01/10/2013 page4)