Greening the urban jungle

Updated: 2012-11-23 06:52

By Doug Meigs(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Li Guiyi is the director of Hong Kong's Zero Carbon Building. The building actually produces surplus electricity and pumps it back to the public power grid. The building will open to the general public in mid-December. |

The Zero Carbon Building in Hong Kong marks a milestone in the city's trend to green architecture. Although the design clashes with local demands for hyper-density, renewable energy technology is still making inroads across the territory. Doug Meigs reports.

Hong Kong's greenest building looks tiny compared to its neighbors in Kowloon Bay's former manufacturing district. One day the neighborhood will be transformed into Hong Kong's next central business district. But for now, the Zero Carbon Building (ZCB) sits amid the tranquility of the surrounding park, dwarfed by the old factory buildings. All around, contemporary monolithic towers stretch skyward above the drab, post-industrial landscape.

The ZCB is the city's first building capable of producing more energy than it consumes. "This particular zero carbon building goes one step further," says Li Guiyi, director of the new ZCB. "It also offset energy consumption by way of transporting and manufacturing major construction materials during construction. There are actually very few (buildings like this) in the world."

Photovoltaic solar panels cover ZCB's sloping rooftop, positioned to maximize exposure to the sun. Li explains the building's energy-saving intricacies while standing in a long, open-air corridor. The building's long southeast-facing layout facilitates natural ventilation, maximizing exposure to prevailing winds during the oppressively summer months. Sunlight pours into the building from floor-to-ceiling windows designed to reduce heat transfer.

Bigger isn't better for carbon-neutrality, Li says. Wearing a white button-up collar shirt and slacks, he talks about the ZCB with the zeal of an engineer, enthralled by the building's elegance. Li has more than 20 years' experience as an environmental consultant.

In the basement, he gestures to a bio-diesel fuel generator which is operating. The unit is fed by waste cooking oil, collected from local restaurants and reprocessed. That generator supplies most of the building's electrical needs. Surplus energy - estimated at 99 megawatt-hours per year - pumps back to Hong Kong's public power grid.

"It's not our intention to have many replicas of this building. Our intention is to have the technologies displayed here replicated wherever possible and realistically," he says, noting that the building is using more than 80 different technologies, some testing on-site for the first time in Hong Kong. Once it opens to the general public in mid-December, the building would also act as an educational center for students and industry stakeholders.

At a height of only two floors above ground, the ZCB is unusually small for Hong Kong. Pervasive land scarcity has made local real estate among the most expensive in the world. Crowded, compact skyscrapers form an integral part of Hong Kong's hyper-dense urban landscape. "In our case, it was feasible to achieve zero carbon emissions, but with a high-rise building, technically, it's still a dream," Li says.

The spacious open land abutting the ZCB would have garnered a fortune if converted into a massive office or residential tower. Instead, it is the site of Hong Kong's first native urban woodlands. Gardeners are busy, planting trees as Li steps out to show the grounds. A development here would have blocked natural air ventilation and solar power, ruining the ZCB's primary energy-saving designs.

Buildings are responsible for the majority of Hong Kong's pollution. They consume 90 percent of the city's electricity and generate 60 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Something needs to change if the government is going to achieve its 2020 target objective of slashing the city's carbon footprint by 50-60 percent from 2005 levels. The ZCB provides a case study for an extreme solution.

ZCB, the Construction Industry Council project, was completed in June with government assistance at a cost of HK$240 million.

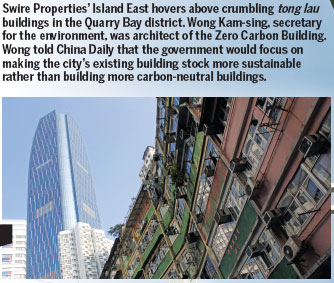

Li worked with every stage of the building's construction, from planning to operations. The architect of the project was Wong Kam-sing, current secretary for the environment and the Hong Kong government's most senior environmental official.

Wong told China Daily that he believes the government would not develop more carbon neutral buildings, but instead, will focus on revitalizing the old neighborhood.

"I'm not saying the ZCB is not important, but in Hong Kong's high density context, probably we have to address the energy issue in a more holistic way. How to turn our existing stock of buildings into lower carbon buildings is our most difficult challenge," he said during a Q&A session of "Architecture and Energy," a seminar hosted by the Civic Exchange and the German Consulate on Oct 12.

Local commitment to energy efficiency is increasingly government-regulated. During the past three years, the Buildings Energy Efficiency Funding Schemes provided matching subsidies exceeding HK$390 million for roughly 6,000 buildings to upgrade energy performance of common areas. As of September, the newly enacted Energy Efficiency Ordinance requires that all new buildings meet minimum efficiency standards for air-conditioning, electricity, lighting, lifts and escalators.

Also during 2012, Hong Kong's environmental assessment - Building Environmental Assessment Method (BEAM) - upgraded its highest evaluation standard, "BEAM Plus", to a more stringent set of criteria. Since last year, the government has required new properties to meet the BEAM Plus criteria to qualify for additional gross-floor-area concessions.

Swire Properties was one of the founding members of Hong Kong's BEAM Society in 1995. The company's sustainable development manager, Amie Lai, says the developer plans, voluntarily, to shave 50,000 megawatt-hours between 2009 and 2016 across the company's investment property portfolio in both Hong Kong and the mainland.

"Our business strategy is to create long-term value, and we think that sustainability is part of that guiding principle for all of our activities," Lai says, speaking from a meeting room inside Admiralty's Two Pacific Place. The building, which was completed in 1990, later was retrofitted with newer energy-saving light fixtures and ventilated by a more efficient central air-conditioning chiller.

Lucien Gambarota, a Hong Kong-based renewable energy inventor, says elevated governmental regulations are a boon for his business. In the BEAM Plus guidelines, developers obtain credits if they implement renewable energy systems satisfying up to five percent of the building's energy demand.

As a result, Gambarota says industry demand surged. "There are not any new buildings designed by an architect that don't have some (renewable or sustainable) feature, designed because of law or personal feeling," he says, turning from an experimental solar panel rig with which he had been tinkering.

Gambarota's industrial lab is tucked into a remote lot northeast of Sheung Shui. His green energy inventions are crowded behind the property's gate wall. There's a wind turbine fueling a compressed air chamber, and a thick rubber speed-bump hooked to a generator; electricity-generating bikes nestle amongst heavy machinery and parts.

He entered the renewable energy market seven years ago, concerned about the growing pollution problem. The Italian expat - a former toy and watchmaker - says he began developing wave-powered generators; however, thieves stole his trademarked Motorwave prototype after he installed it at Po Toi Island for a test.

His most successful green invention is Motorwind: small wind-turbines capable of operating at low wind speeds. He sells the brightly colored plastic turbines, ranging from 10 centimeters to 150 meters in diameter, to vendors in 45 countries. Schools often want the small turbines to supplement their renewable energy curriculum. Local construction companies also make large orders. For example, Gammon had an 800-turbine installation at the entry of its construction site for the Tamar Government Headquarters.

Gambarota unveiled the turbines at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) in 2007. Now that HKU's Centennial Campus is nearing completion, he says a Motorwind system will be installed by the month's end.

Gambarota says obstacles to renewable energy include the public's lack of electrical understanding (a safety risk for general consumers wishing to install powerful home systems) and the technology's intrinsic unreliability (dependence on windy or sunny days, etc). He also laments that some developers could manipulate governmental renewable energy mandates.

"Whatever money you are going to put into renewable energy, it can easily be offset by having a better building design. Renewables on the rooftop might generate 0.5 percent of the energy the building needs. This 0.5 percent could easily be offset by installing double or triple-glaze windows (but that costs even more)," Gambarota says. "You can clearly see from the beginning they are not up to designing the best building. They are just trying to make money and look green. It's just image."

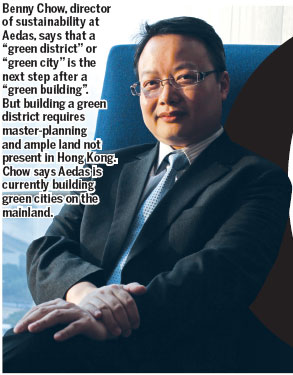

Speaking from the lobby of an international architecture and design firm in a Quarry Bay office tower, the director of sustainability at Aedas, Benny Chow, cheerfully emphasizes that skyscrapers are incredibly efficient and important to the city's success. "High performance is key to the success of Hong Kong. It's good to be green, but at least we have to be high performance," he says.

However, Chow says lack of large-scale environmental master-planning has resulted in the city's horrendous air quality. A high-rise wall effect, traps pollution and blocks natural airflow, while government regulations - such as height limitations - and splintered private ownership of older neighborhoods hold Hong Kong back from progressing from "green buildings" to "green districts". Despite these obstacles, Chow envisions the greening of the concrete jungle.

"The former Kai Tak Airport is a large piece of land where they can do a large development in the middle of the city, but with the rapidly changing housing policy I'm not sure," he says. Tentative plans for the CBD2 (which also includes Kai Tak), feature numerous greening initiatives already: a district-wide cooling system, an eco-friendly monorail, and urban planning that emphasizes pedestrian-friendliness, greenery and integrated commercial and residential space to save commuting time/pollution. Otherwise, Chow says the next best potential for a green district might be the less-developed portions of northwestern New Territories near Yuen Long.

Spatial constraints for green master-planning in Hong Kong are considerably greater than on the Chinese mainland, where Aedas is currently working with a number of so-called "green cities", such as the Panda Green Island in Sichuan. Chow says the river island development could become part of a nationwide effort to develop a green city/district for every province (the construction is in its early stages).

Back in Hong Kong, renewables continue to infuse a host of other projects. Tuen Mun's "Science Park Phase 3" hopes to achieve carbon neutrality by 2025. Meanwhile, Hong Kong's two semi-public power utilities are advancing a variety of green energy projects. In some cases, they now allow the private sector to feed renewable energy systems back to the public grid.

Aside from the Zero Carbon Building, another energy-neutral project was recently completed. Off the eastern coast of New Territories, China Light and Power is sponsoring the project to supply Operation Dawn (a drug rehab facility based on the remote Town Island since 1976).

During a phone interview with CLP Chief Engineer Raymond Ho, he says the project was completed on Oct 31 and is already satisfying residents' power needs, though it's not yet fully operational. Ho visited the island six years ago when preparing for the installation. He saw old diesel generators working only eight hours a day, needing constant refueling. When generators died, all lights went out - along with power for kitchen freezers.

Rehab inhabitants now enjoy refrigerated food and lighting around the clock. CLP financed the HK$10 million construction of the Town Island Power Supply Program as a pilot initiative. Together with students at the HKU and Hong Kong Polytechnic University, they will monitor ongoing progress with a view for territory-wide application.

Ho says the technology is still rapidly changing. He refuses to speculate a perfect scenario for widespread local use. "To construct a solar system we need a very large amount of flat open land which is hard to find. A photovoltaic system requires five football fields to supply 100 people on the island," he says. "We are seven million here. If we need to supply by wind, we can estimate that we need to cover the whole Kowloon peninsula with wind turbines, to meet only 4 percent of HK's overall power demand." That amount of space is one luxury that affluent Hong Kong cannot afford.

|

The Zero Carbon Building is located in Kowloon Bay, surrounded by old factories and new high rises. Buildings consume 90 percent of Hong Kong's electricity and generate 60 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. The government wants to slash the city's carbon footprint 50-60 percent by 2020. Provided to China Daily |

(HK Edition 11/23/2012 page4)