Among the 1 percent

Updated: 2012-11-16 06:39

By Andrea Deng(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Lau Kwok-chang, assistant principal of the Delia Memorial School (Broadway), a middle school with a vast majority of its students coming from the ethnic minority, said while the Education Bureau has taken measures to support minority students learning Chinese, the most important step to set up an alternative curriculum and assessment system for Chinese as a second language remains undone. Andrea Deng / China Daily |

Hong Kong has no standardized, evolved system for teaching Chinese as a second language. Critics charge that places students of non-Chinese-speaking ethnic minorities at a great disadvantage in achieving higher education. They point to the figures that show, only about 1 percent of ethnic minority students manage to get into local universities. Andrea Deng reports.

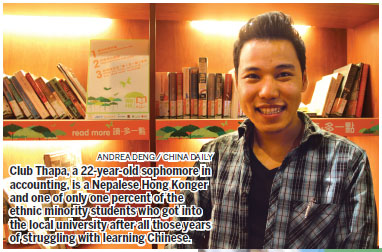

The young man striding with light steps, briskly down the coffee shop looks like an average university student: casual plaid shirt, fringe tidily gelled back. Club Thapa, a 22-year-old sophomore in accounting, is a busy young man. His schedule, outside his regular studies is fully booked. There's the part-time job at an accounting firm; the entrepreneur club at the university; joining a competition, as part of the team trying to come up with innovative ideas. On top of that, Thapa also works as a coordinator for an organization that provides working holiday opportunities to overseas students.

In short, there's nothing particularly unusual about the way this Nepalese-born scholar, who moved here with his partents when he was 10, occupies his time. Most Hong Kong students are busy, ambitious and enterprising, soaking up knowledge and experience like a sponge, arming themselves for intense competition in the job market after graduation for better future prospects.

What distinguishes Thapa is that he is one of only about a dozen minority students who somehow managed to overcome the hurdle of mastering the Chinese language, and managed to get into local universities every year.

Thapa feels pretty lucky, being among the "1 percent", set apart from the 99 percent from the same ethnic minority who were unable to enter local universities. After graduation from either the fifth or sixth grade, some of his middle school classmates went to great lengths to earn a diploma, while many others find their way into jobs in restaurants, grocery stores, singing for their supper, DJing at bars or in the construction trades. Job opportunities for middle school graduates of ethnic minorities are limited.

Thapa worked hard, pursuing his passion for numbers after finishing the fifth grade. He took a year-and-a-half in night school, getting a diploma in accounting. He had not worked very hard developing fluency with the Chinese language during middle school. His ability with the language was no better than that of his peers. Then he took a bet, and wrote the Chinese test in the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), which is equivalent to a Grade Three level of Chinese language ability. He scored a C.

The program Thapa undertook is taught in English anyway. So his failure to achieve a standing of excellence in Chinese was not a big problem.

In 2011, only 17 of the more than 1,000 non-Chinese-speaking students studying in public schools and Direct Subsidy Scheme schools and who sat the Hong Kong Advanced Level Examination were offered placement at local universities, according to the Education Bureau.

Fermi Wong Wai-fun, the iconic minority rights activist who is the executive director of Hong Kong Unison, a non-governmental organization for minority benefits, said while theoretically taking the GCSE Chinese test can be an alternative to the Chinese test under the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education (HKDSE) - which native-Chinese-speaking students take, the reality is that less-than-satisfactory Chinese language capability does serve as a barrier to minority students in a number of undergraduate programs, those much richer in local content: social worker, news reporter, nurse, Chinese history and so on.

Additionally, although programs taught in English are not uncommon at local universities, for some of the courses, group discussion or even course materials could still be done in Chinese. It is not unreasonable that when the university admissions board flips through the transcripts of the thousands of applicants, they would opt for candidates who may handle both Chinese and English with ease.

Even sub-degree programs are not friendly to minorities, since advanced Chinese or Putonghua is usually a required course.

Thapa knows that his future is not assured, despite his admission to university. He began bearing down on his Chinese skills a few weeks ago and attends Chinese classes every weekend. He's set a goal of being able to read a Chinese newspaper within five years and hopes to have sufficient proficiency by the time he graduates to get a job at a local accounting firm.

He recalled a few years ago seeing a Chinese friend thumbing through the classified ads of a newspaper and two weeks later, his Chinese friend was able to change jobs. It takes at least a month for his Nepalese friends, and people from other ethnic minority to find jobs. Usually it's by referral - because people from the local ethnic minority cannot read or write Chinese well.

"If you don't have a degree, and you can't even read Chinese, you'll be marginalised. If you don't attend university from where you start to build up your network, you can only know Nepalese people in your community," said Thapa, in accented Cantonese, as he elaborated his theory about why his minority friends have fewer opportunities.

"The minority community are detached from the local community. If somebody told the minority people what the society needs, our parents would have instructed us to take Chinese very seriously.

"To be honest, I don't think we've (the ethnic minority) worked as hard as the local students. There was no incentive to encourage motivation - when you think about what is the best work in the community, your relatives are construction workers, or you work at the bars. There is no inspiration, no example. And then you experience the same, that you can only find a job which does not require Chinese," said Thapa.

He cited the ancient Chinese idiom, "one who stays near vermilion gets stained red, and one who stays near ink gets stained black." Thapa agreed that he has been influenced by his local Chinese classmates ever since university and tends to act the same. But it's not the same case for his middle school classmates.

The obstacles that they face from arduous endeavor of learning a foreign language known to be difficult, may be affected by complex social psychology. However, pundits believe that it is simplistic to characterize the issue by saying that new immigrants are "not working hard enough".

At the Delia Memorial School, Broadway, 90 percent of the students come from ethnic minorities. Lau Kwok-chang, assistant principal of the school, noted that children of non-Chinese-speaking minorities are in morass when they come to face languages. While they speak their native tongue with their parents at home, they do not actually learn their native language in a serious way. Living in Hong Kong's bilingual society means speaking two second languages - English and Chinese. While learning a foreign language is a process of finding the common aspects with the native language, it would have been more effective to start to teach them their second language using their native tongue. In reality, however, learning English may be easier than learning Chinese, a hieroglyphic and tonal language that requires, in large part, rote memorization, which drives away many.

Unlike the native-born Chinese speakers who can easily associate the characters with the culture, a minority child can turn only to a friendly Chinese-speaking neighbor - if he is lucky enough to not live in a community surrounded by people of the same ethnic minority, where he is likely to drown in the difference of "shui" and "shui". Studies show that a first grade Chinese-speaking student can recognize about 490 characters, a sixth grade student recognizes between 2000 and 2500 characters. A minority student knows only between 100 and 500 characters after graduating from elementary school.

There is hardly a teacher in Hong Kong who knows how to teach Chinese as a second language. Middle school Chinese teachers in the so-called "designated schools", which enroll a vast majority of the minority students, are accustomed to teaching Chinese-speaking students. According to Wong, from Unison, most lack the necessary skills to teach a non-native Chinese-speaker - who may have learned to speak Chinese from television, can neither read nor write. Teachers without the necessary training and expertise also neglect the fact that most minority students know nothing about Chinese culture and it is difficult for them to associate the language when they are not familiar with the culture, for example, learning phrases from situational dialogues related to Chinese New Year.

Hong Kong is still learning the baby steps in how to train instructors in teaching Chinese as a second language. Only the Faculty of Education of The University of Hong Kong has started a program to provide training support and that was only a couple of years ago. Only a minimal number of students enrolled in the program during the first two years. While the Chinese mainland has developed expertise in the subject over a few decades, and both Singapore and Taiwan developed their own systems of teaching foreigners Putonghua, Cantonese is dominantly spoken in Hong Kong and traditional Chinese and an independent system to study the language needs to be devised for practical use.

While the inefficient and ineffective ways of teaching minority students the Chinese language drain the energies of teachers, the Education Bureau has firmly insisted that an alternative curriculum and assessment of Chinese as a second language is not necessary, despite the NGO and the schools' strong demand for it.

In reply to China Daily's enquiry, a spokesman for the Education Bureau said that the current Chinese language curriculum framework is "robust, vibrant and flexible for schools' adaptation, in accordance with the aptitudes of the students, including non-Chinese-speaking students". An alternative curriculum and assessment with "pre-set simpler content and lower standards would limit the range of learning opportunities for non-Chinese-speaking students with different needs and aspirations and also undermine their opportunities for further studies".

That perception of "pre-set low level" is where minority rights activists disagree with the education bureau. Minority interest groups argue that while it is harsh that minority students - without much support to learn Chinese progressively - are assessed according to the same standards as the Chinese speaking students, the government is only implementing "formal equality" instead of "substantial equality".

The Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC) holds the view that if a college cannot appraise a student's Chinese capability with a just and fair standard, it may constitute indirect discrimination that violates the Race Discrimination Ordinance.

Tse Wing-ling, convener of the Policy and Research Committee of the EOC, argued that the logic behind the minority education policies of the Education Bureau has been fundamentally faulty.

"We should be talking about inclusive education, meaning that education should take into consideration the situation of minority groups, not about 'integration' of the minority to the 'mainstream' and taking a 'sink or swim' approach," said Tse.

Currently, more than 30 different "designated schools", which enroll a vast majority of the 14,100 minority students in Hong Kong, have their individual systems and materials in Chinese language teaching. The Supplementary Guideline written by the Education Bureau, which outlined the guidelines and reference of how to teach minorities, has no mandatory force applied to the "designated schools". While a small number of minority students are struggling with learning Chinese along with the Chinese-speaking students in the "mainstream" local schools, with their teachers simply not capable of taking extra time for minority students trying to tackle Chinese learning.

"It (the current apportionment of minority students) is a very outdated approach and it is against the international trend. It will only bring more problems than solve them," Tse said.

To initiate a review of education policy regarding ethnic minorities, which has attracted only a sliver of public attention, Unison plans to take legal action against the Education Bureau by the end of November, if the government remained unwavering in its stance on the contention that the policy to allow "designated schools" enrolling large majority of minority students would be a less favorable treatment, since it "segregates a person from other persons on the ground of race".

Tse, of the EOC, told China Daily that the commission will seriously consider providing support if legal action is taken.

No matter how "robust, vibrant, flexible" the existing Chinese curriculum is, it is a hard fact that the number of minority students attending university is way below proportion among the entire student population of Hong Kong, said Tse.

There is justifiable reason for concern that the situation could grow worse. The adjustment of academic structures since 2009 requires that all the local students present Chinese test results, unlike in the past when students who did not attend "mainstream" schools could take another second language test. Meanwhile, the number of minority students is growing every year. There were only 8,900 minority students during the 2007-2008 academic year. The number has now increased to 14,100. The situation that 99 percent of them fail to learn Chinese just cannot be left unchecked.

(HK Edition 11/16/2012 page4)