Just tryin' to make a living

Updated: 2012-08-17 06:49

By SL Luo(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

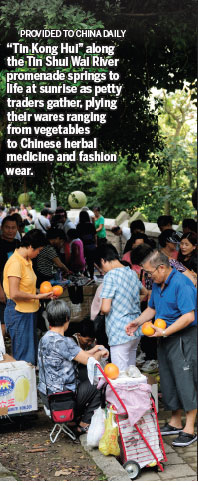

There's a popular movement growing in Tin Shui Wai to legalize and legitimize 'Tin Kong Hui', the popular riverfront dawn market. While observers say the ruthless prosecutorial attitude of the authorities seems to have abated, it isn't enough to lift the shroud of misery clinging to the destitute. SL Luo reports.

June 26, 2006 started out like any other day, for the residents of Tin Shui Wai, a part of the city infamously branded, Hong Kong's "City of Sorrow". The inflow of new immigrants went on unabated compounding the community's unparalleled density. The indigent, the depressed and tragically dysfunctional families, from whom erupted periodic eruptions of horrific violence.

An elderly vendor, Law Kwong-ching, hawking his wares at "Tin Kong Hui" (Dawn Market) near the banks of the Tin Shui Wai River drowned, while the authorities were pressing a campaign to clear the streets of unlicensed sellers. Law had no license. He knew he wasn't supposed to be there. And at first sight of the hawker patrol the old man took to his heels and before the authorities could catch him, he jumped into the river, and was swept away by the muddy torrent.

A wave of grief for the drowned man swept over the city, followed close on by an up welling of public indignation. Law, a father of seven, in death became an iconic figure, hailed as a champion of the oppressed.

A Coroner's Court later ruled that Law's death was accident. His family was not entitled to any compensation.

Today, more than six years after his death, Law Kwong-ching has not been forgotten by the people of Tin Shui Wai, and the incident that led to his death has grown into a "cause", spawned by simmering anger, fueling demands for the authorities to give the people of the district a better and fairer deal.

Tin Shui Wai (literally meaning bounded by heaven and water), is tucked away in a remote corner of the northwestern New Territories. Three decades ago, before the sprawling enclave of common houses is sprung up, it was a wide expanse of swamp land and fish ponds.

In that relatively narrow time span, the population occupying the expanse swelled to 30,000 in the mid-1990s, before exploding to its present day population of about 280,000 people.

Despite the poverty of many of those who live their lives there, the cost of goods and services in the enclave is wildly inflated over prices paid for the same goods and services in the city's wealthier districts. The cost of food and other daily necessities runs roughly 20 percent higher, by comparison. Most of Tin Shui Wai's population earn less than half of what workers in more affluent Wan Chai earn in a month on average. Community leaders denounce conditions there as absurd and approaching insanity.

The injustice underlying this troubled scenario has been laid bare - Tin Shui Wai is at the mercy of a virtual monopoly, controlled by two of the city's biggest conglomerates, with absolute domination of foods and commodities, and the overcrowded shopping malls, where they are sold.

From the economic standpoint, traveling to Wan Chai or Central to take up a full-time job which pays as much as HK$8,000 or even HK$10,000 a month is not practical, given the lengthy travel times and high public transportation costs. Even the newly-inaugurated HK$600 monthly transportation subsidy offered by the government to encourage workers in outlying areas to look farther afield to find jobs, comes attached to a litany of restrictions. The subsidy has done little to stir the enthusiasm of Tin Shui Wai residents for taking up employment outside the district. Response to the subsidy is muted.

The morning markets at Tin Shui Wai arose more or less spontaneously, in the mid-1990s as elderly, retired men and housewives took the plunge and started selling produce and other goods to augment their families' incomes, without the government's blessings. These are fiercely proud people who have refused to put themselves on the dole and the sense of social opprobrium they would feel if they asked for social welfare assistance.

When I visited the neighborhood, I was regaled with tearful tales of poverty, depression, hopelessness, joblessness and isolation.

Painful memories of Law Kwong-ching are still very fresh.

Madam Fung, 52, says she's still on medication for depression after running afoul of the law for hawking at "Tin Kong Hui".

She was arrested once, had all her goods seized, hauled before the courts and fined HK$480 - nearly three times her daily earnings as an illegal hawker.

"I started hawking at Tin Shui Wai several years ago after being retrenched as a textile worker, when local factory operators began moving north to the mainland.

"I've never thought of applying for welfare assistance, but I have to support the family," says Fung, who has since quit "Tin Kong Hui" for fear of being arrested again.

"I was under tremendous pressure, almost driven to the wall. The raids (by anti-illegal hawking squads) never stopped. I'm still on medication to control the depression. And I'm still having nightmares of having to run for my life each time the raids came," she says.

According to Fung, anti-hawking officers would appear from nowhere, charge the stalls without warning and bundle them into a van.

"It's frightening every time I think of it," she says.

"But, since the Law Kwong-ching tragedy, they have relented somewhat and would give the hawkers ample time to pack up and leave without making arrests," adds Fung, who has moved to Lau Fau Shan where he sells sundry goods.

"I feel much safer there," she says.

Madam Kam, 47, who has been doing her rounds at "Tin Kong Hui" for the past five years, remains defiant.

She too was arrested once, fined HK$450 and had all her merchandise worth 1,000 yuan confiscated.

"I enjoy being a hawker. Depending on welfare assistance won't do. It's not enough as I have three children attending school in Hong Kong," says Kam who emigrated to the HKSAR from Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in 2008.

For Fung, Kam and Madam Pang, another retired illegal hawker, the message to the authorities is loud and clear - legalize "Tin Kong Hui".

"We belong to the destitute class. It's impossible to make ends meet in Tin Shui Wai even with a job, let alone with none," says Pang.

"Give us a place to do our business in peace, free from fear of harassment," pleads Pang, holding back tears.

She appealed to the big business players in the district to offer, say a couple of hours of work, for housewives or elderly residents so that they can both supplement their family income while having some time to look after their children.

At "Tin Kong Hui", the action goes on from six to nine every morning with or without the invading anti-hawking squads.

According to some of the 60-odd hawkers still in business, the number of raids may have subsided to about two each week from a peak of two every day in the past.

Legalizing "Tin Kong Hui" still seems a distant dream. Obstacles abound. Talks initiated by social aid organizations have been held with relevant government departments, but nothing concrete has emerged.

One of the main obstacles has a political overtone. Legislators and district councilors have been talked to and briefed on the problems confronting Tin Shui Wai, but prompt action doesn't seem to be on the cards.

"They're (the legislators and councilors) sandwiched in the middle, with voters to be answerable to. Other residents may not be on the side of the hawkers and see those dawn markets as more of a nuisance than easing poverty and helping the poor and the grassroots," a source explained.

"They understand the situation but, at the same time, have a lot of reservations. How do you deal with those complaints from those on the other side of the camp?"

But social aid veterans, who have been leading the battle for the hawkers, are confident that, ultimately, it will be done.

One of those is Athena Wong, a project officer with the Community Development Alliance (CDA), a social group backed by Oxfam Hong Kong, which started looking into the Tin Shui Wai problem earlier in 2008.

The group disputes the government's insistence that personal family problems are mainly to blame for the district's woes.

"We were shocked by the series of family tragedies at Tin Shui Wai as far back as 2006, and realized we need to get to the bottom of the issue," says Wong.

"We're convinced that the problems go further than family difficulties. We believe it's society's mismanagement. We have to resolve this under the 'Below The Lion Rock' spirit which shows how a resilient and self-reliant Hong Kong society struggles to overcome adversity," she says.

Tin Shui Wai is the first project CDA was assigned to Tung Chung's Yat Tung public-housing estate, where the poverty problem is "on an equal footing" with Tin Shui Wai.

A research study in 2008 concluded that the problems facing Tin Sin Shui were "incalculable" - fueled by an over-concentration of newly-arrived emigrants, a huge cultural divide, juvenile delinquency and rampant unemployment.

"A lot of these people are in desperate need of jobs, but job opportunities are scarce and employers are demanding certain academic qualifications. These people have none.

"CDA believes that community problems cannot be resolved through counseling, mutual help groups or social visits alone," says Wong.

"We believe that something has to be done to revamp government policies. It must go straight to the people affected to ask them what their problems are. There must be a dialogue between the government and the people, to get to the root of these problems and I think CY (Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying) knows this," she says.

"Tin Shui Wai truly reflects these problems. It's the first district in Hong Kong we started to focus on to help the residents overcome their difficulties. We want to start a campaign at Tin Shui Wai to correct all the abnormalities. We are appalled by them."

As for "Tin Kong Hui", Wong says the CDA had, at one time, secured an agreement with the authorities top leaders for some place for residents to continue their hawking. But it lasted only a month due to objections from certain district councils.

The alliance itself had also proposed a trial scheme for the operation of a whole-day market in the new town. The nitty-gritty part has yet to be worked out.

With or without the Fungs, the Kams and the Pangs, life at "Tin Kong Hui" goes on.

"It's their survival. With our continued support and their determination to live as dignified human beings. Ultimately, we can and will win," says Wong.

(HK Edition 08/17/2012 page4)