Shark feeding frenzy

Updated: 2011-11-17 07:08

By Doug Meigs(HK Edition)

|

|||||||||

|

Volunteers raise awareness on shark fins in Mong Kok in September. Provided to China Daily |

|

Ho Siu-chai has sold shark fins for more than 30 years in Hong Kong. Doug Meigs / China Daily |

|

Shark fin soup imposes a heavy price on pocketbooks and environment, say conservation groups. Provided to China Daily |

|

A man fins juvenile sharks in Hodeidah, Yemen. Provided to China Daily |

The tradition of serving shark fin soup is devastating global shark populations. The State of California and City of Toronto banned sales of shark fin in October. Activists hope global momentum prompts new regulations in Hong Kong. Doug Meigs reports.

Half the world's harvested shark fins pass through Hong Kong, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). On the streets adjoining Des Voeux Road West and Bonham Strand in Central, deliverymen can be seen lugging crates of the precious merchandise through bustling traffic. Giant shark fins - with price tags as high as HK$5,000 per kg - radiate a sense of affluence from storefront displays along Des Voeux Road West. Inside the shops, dried fins of all sizes spill from overstuffed bags and shelves. Signs warn: "photography prohibited". Vendors don't appreciate gawking tourists or camera-toting environmentalists. Bathed in pungent aromas of traditional Chinese medicine and seafood, customers peruse dried wares. Hong Kong's Marine Products Association estimates that roughly 200 local retail and wholesale sellers occupy the blocks in the immediate vicinity, making Sheung Wan ground zero for a controversial industry.

Glancing out at the scene, Ho Siu-chai continues working at his desk at the back of his shop on Des Voeux Road West. Ho, now 55, began selling shark fins in the neighborhood more than 30 years ago. He started working for another trader and eventually opened his own store. He sells different dried marine products, but shark fin provides more than half his income.

Ho said environmentalists are hurting his bottom line. "The industry has changed a lot. Since the advocacy came, we have less business to do, but the costs have increased. Many people have become unemployed and had to change jobs," he said.

From 2001 to 2010, the Census and Statistics Department records show annual shark fin imports falling 6 percent to roughly 9.9 million kg, while annual exports quantities dropped 23 percent to 5 million kg exported in 2010.

The fins are destined for shark fin soup, a dish dating back to the Song Dynasty. It was also popular with emperors of the Ming Dynasty. During the past century, the soup became a staple of weddings banquets and fancy Cantonese restaurants. Increasing prosperity on the mainland translated to booming demand. Cost per bowl can exceed HK$780 for (otherwise tasteless) dried shark cartilage boiled in chicken broth with seasonings. The fin is prized for its chewy texture.

The local shark fin controversy began escalating in 2005; when Disneyland removed shark fin from menus. Two years later, the WWF launched the first local shark campaign seeking shark-free pledges from corporations. Momentum continues to build. Hong Kong has 16 different groups coordinating their efforts, wholly or partially dedicated to the preservation of sharks. The groups meet regularly to organize social media campaigns, flash mobs, performance art, even anti-shark fin concerts to raise awareness.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which chronicles wildlife under threat of extinction, the number of at-risk or endangered sharks, rose from 15 to 181 species in the past 12 years.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations began encouraging countries to adopt "International Plan of Action for Management and Conservation of Sharks" (IPOA) since 1998. The FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department's website lists 13 national plans implemented around the world during the past decade. Simon Funge-Smith, senior fishery officer for FAO in Asia, said the number of shark IPOAs remains disappointingly low, especially among the largest shark fishing nations.

The FAO database FishStatJ shows that the quantity of "sharks, rays and chimeras" harvested, peaked at 900,179 tons in 2003. That's more than triple the quantity the department reported captured in 1950. Harvests have gradually declined since 2003. The quantity captured in 2009 (721,163 tons) is almost back to the level of 20 years ago. "This is due to less targeting, perhaps lower reporting," Funge-Smith said.

Tabloid news and cinema tend to typecast sharks as ravenous monsters. Cue the "Jaws" soundtrack. But they also regulate marine ecosystems. Scientists say the shark is also one of the world's oldest surviving species, predating the age of dinosaurs by 100 million years.

Studying sharks in open ocean environments would be a logistical nightmare. The (sometimes clandestine) fin trade is similarly murky above water: Fins are often re-sold multiple times. Traders label fins with market names unrelated to species. Hong Kong's import records note only the processed state of the products, i.e. salted, or dried vs unprocessed, rather than scientific names. Vendors jumble fins from different species in the same bags.

Market confusion means consumers don't know what they're eating. A Hong Kong-based NGO dedicated to oceanic awareness, Bloom, hired a team of scientists at City University of Hong Kong to study genetic and mineral composition of fins sold in Sheung Wan. "Some of the fins you can tell very easily what type of shark they're from, based on the texture and the size, but for others it's much more difficult," said Margaret Murphy, one of the lead scientists researching the issue since 2010.

She said lack of data confounds attempts to gauge sustainable shark populations. Many shark species remain a mystery to scientists. One species sampled in the study was carcharhinus altimus, the "bignose shark". Murphy said a fisherman might have randomly caught the shark listed as data-deficient in IUCN rolls, and they sampled the species by coincidence. "Or it could be that the more accessible sharks, living at depths nearer to the surface, are not as available and fisherman are going deeper."

The report is not yet complete, but Murphy said research has found IUCN endangered shark species in the samples. It has also found evidence to refute concerns that shark fin soup poses any health risk from bioaccumulation of trace contaminants such as mercury.

Silvy Pun, an officer with the WWF in Hong Kong said the certification framework is essential for local traders to continue, but international or locally certified "sustainable" does not yet resonate here. In October Canada announced the opening of the world's first (and only) Marine Stewardship Council certified "sustainable" shark fishery for spiny dogfish. Fillets from the species sell in Britain as "rock salmon". The WWF in Canada is acting as advisor on the project.

"This issue is kind of complicated," Pun said. "We think you shouldn't eat shark fin, because we consider it from an ecosystem perspective. But as far as (this isolated fishery) is sustainable, and doing minimal harm to the environment, we think it is fine to eat it."

WildAid's website claims up to 73 million sharks are killed every year to meet the increasing demand for shark fin soup. The result: "one-third of open-ocean shark species are currently threatened with extinction, with certain populations experiencing a 99 percent population decline."

The international charity was the first to target the shark fin industry. WildAid began its Shark Conservation Program in 2000, with the goal of shaping consumer perception of shark fin soup within China. Celebrities have joined the cause, including Yao Ming, who swore not to eat shark fin soup in 2006.

Even before population decline, data became available, WildAid co-founder Steve Trent said Hong Kong's shark imports raised conservationists concerns that there may be another "wildlife gold rush." Hong Kong was a major hub for ivory, until the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) banned the trade in 1989.

"A lot of traders lost their primary source of income and revenue. Almost overnight, those same companies shifted their trade in ivory to shark fins, and that's what first raised our attention to the potential threat to sharks," he said.

Today, most of the world's shark fins head to the mainland or Vietnam, where factories process the product. Stock then comes back through Hong Kong, to be used for domestic consumption or re-export to the mainland or abroad. Recent bans in North America cut off the market for two major Chinese communities.

The US state of California banned sale and possession of shark fin on Oct 7. Toronto passed a similar ban on Oct 25. Shark fin soup aficionados often dismiss criticism as racist or a result of cultural misunderstanding. A Chinese American politician helped to change the ethnocentric debate in California.

"What happens here could give some leverage to what's happening in Hong Kong (and the Chinese mainland)," said California Assemblyman Paul Fong, who migrated to the US from Macao at age three. Fong introduced the bill that made California the fourth US state to ban shark fin. He said California Congressman Sam Farr is working on a nationwide proposal.

Billionaire steel tycoon, Ding Liguo, a delegate to the National People's Congress, proposed a nationwide ban for China in March 2010. The current status of his proposal is unclear. Hong Kong Shark Foundation created an online petition at change.org, demanding the local government "make it a public policy not to serve shark products at official functions". Similar petitions failed in the past.

A spokesperson for Hong Kong's Environmental Protection Department said: "We do not think it is appropriate to lay down guidelines to regulate the kind of food to be consumed at official functions," though internal guidelines and budgets would typically keep shark fin off of publicly funded official banquets. The spokesperson explained that Hong Kong is already committed to protection of endangered wildlife recognized by CITES.

CITES has protected three shark species since 2002 (the great white shark, basking shark and whale shark). An attempt to restrict trade in four other species (porbeagle, scalloped hammerhead, oceanic whitetip and spiny dogfish sharks) narrowly failed in March of 2010.

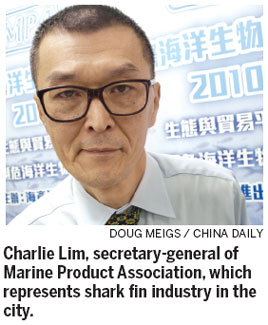

The Marine Produce Association, which represents Hong Kong's shark fin traders, attended the conference. Charlie Lim is the association's general secretary. Lim appears regularly as the official voice of Hong Kong's shark fin traders in the media. He spoke from an office table covered with posters of shark species. Photos from past CITES summits plaster the wall. Illustrated shark species charts decorate the conference room tabletop.

Lim said a ban focused on fins only creates waste in the name of conservation. He said shark meat provides food for 120 million living in impoverished fishing communities, while more lucrative fish go to market along with shark fins. "It's very funny coming out of California or Toronto, you can eat the meat, but the fin, you have to throw away,"

Shark fins account for just about 7 percent of the volume of shark trade, but 40 percent of the monetary value. Finning is a practice in which the fins are sliced from sharks, and the bodies are dumped (sometimes still alive) overboard to drown slowly or be eaten by passing fish. Lim said between 60 and 70 countries have laws against finning. He welcomed stronger regulation of national fisheries, in preference to restrictions imposed upon traders. He applauded the passage of the US Shark Conservation Act this year, requiring boats with shark fins to hold the corresponding number and weight of carcasses.

"All the country people must have a good management for the fishery. If you think your country is over-fishing. Please, stop it," he said. "The NGOs have to draw attention to shark finning to attract income and sponsorship."

Hong Kong-based photographer Alex Hofford countered Lim's point over a satellite phone line aboard a Greenpeace boat in international Pacific waters. "It doesn't matter if the bodies are getting used, but can the current rate of consumption keep up with demand? No. It can't," he said.

He said enforcement of existing laws is lacking. "When you get out to where I am now, it's the Wild West. Sure they can bring in all these laws to make it illegal but what goes on at sea, no one really knows."

Hofford first witnessed shark finning during a research trip to Mozambique in 2006. Migrants to the seaside harvested sharks for Taiwanese gangsters, who bought the fins and buried leftover bodies on the beach in sprawling, stinking mass graves. Images from the trip are featured in the book he co-authored last year with Paul Hilton, titled Man & Shark.

Awareness is growing in Hong Kong, but traditions change slowly, especially at wedding banquets. Elaine Sum is planning her wedding for February. She must decide the menu soon.

"I don't prefer to have shark fin soup, but there is a challenge because I'd have to pay extra money to change it. They bundle it as a set menu. Shark fin sounds very luxurious to have at the wedding banquet; if you don't have it, it's doesn't look good for parents - like their son or daughter is going to marry, and they can't even offer shark fin to the relatives."

(HK Edition 11/17/2011 page4)