Another bucket of sand in the ocean

Updated: 2011-10-11 07:16

By Christopher DeWolf(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

After reclamation for the Central-Wan Chai Bypass is completed next year, no new land can be reclaimed from Victoria Harbour, in accordance with the 1996 Protection of the Harbour Ordinance. As a result, the government is now exploring new locations for land reclamation outside the harbor. Christopher DeWolf / For China Daily |

|

Nearly 3.5 square kilometers of land was reclaimed from Victoria Harbour to create West Kowloon in the early 1990s. This project, along with plans to fill in Kowloon Bay and Green Island, led to widespread opposition to harbor reclamation. Christopher DeWolf / For China Daily |

They stopped filling in Victoria Harbour when people started to worry there would soon be no harbor left. But dumping more earth into the ocean to 'reclaim' land to sustain future development is unlikely to end in the near future. Even now, the government is carrying out a study of possible reclamation sites. Christopher DeWolf reports.

If you are reading this newspaper somewhere in Hong Kong, the odds are you're sitting on a piece of land that was once a part of the sea. Since 1851, more than 60 square kilometers of land has been reclaimed from Hong Kong's waterways, an area greater than Kowloon and nearly as large as the whole of Hong Kong Island.

For decades, much of that reclamation took place along the shores of Victoria Harbour. That will come to an end next year with the completion of reclamation for the Central-Wan Chai Bypass, the last project permitted under the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance, which was passed in 1996 after a rash of reclamation proposals left the public worried that Victoria Harbour would one day disappear under a mountain of landfill.

Land in Hong Kong remains scarce, however, and the government remains intent on keeping reclamation in its toolbox. "It is necessary to resume land production by reclamation of an appropriate scale outside Victoria Harbour so as to provide land to sustain the social and economic development of Hong Kong in the long run," said the Permanent Secretary for Development (Works), Wai Chi-sing, in May. The government is now conducting a study of possible reclamation sites. Public consultations will begin next month.

Though Hong Kong has been reclaiming land for the better part of two centuries, it is a markedly different city than it was a century or even a decade ago. These days, nearly every major infrastructure project meets with controversy. Opposition to major development projects is often fierce, as was the case with last year's protests over the construction of the Express Rail to the mainland. In such a stormy atmosphere, is more land reclamation really feasible?

"I don't think it will be an easy battle, but they'll try," says John Bowden, chairman of Save Our Shorelines, a concern group founded 10 years ago to monitor reclamation projects outside the harbour. Already, the activists that pushed for the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance are gearing up to fight the prospect of large-scale reclamation outside the harbor.

"This is the next step," says Christine Loh, founder of urban development think tank, Civic Exchange.

Nineteen years ago, Loh was a newly elected Legislative Councillor concerned with the large scale of the government's plans for land reclamation. In total, 3.4 square kilometers had recently been reclaimed from the harbor for roads and railways leading to the new Hong Kong International Airport. Hundreds more hectares of reclamation were planned; Kowloon Bay was slated to be filled in, entirely.

"The harbor was rapidly shrinking with all the government plans that were on the table," Loh recalls, so she and Town Planning Board member Winston Chu founded the Society for the Protection of the Harbour in 1995. The following year, after a petition against further harbor reclamation was signed by 175,000 members of the public, Loh sponsored the Protection of the Harbour Ordinance to prevent future reclamation projects.

"We never expected it would pass," she says, but it did.

The government attempted to proceed with several reclamation projects anyway, but the society sued, and the resulting court cases led to a 2003 decision by the Court of Final Appeal that established three requirements for any harbor reclamation projects: a "compelling, overriding and present" need, no viable alternative, and minimum damage to the natural environment.

After losing its court cases, says Chu, "the government swung to the other extreme." Even the smallest proposals for harbor reclamation were quashed, including those for new public piers and marinas. "That led to a raft of complaints from the public that the law was too strict, that it was sterilizing the harbor, that it was preventing the public from enjoying it."

Finally, this year, Chu called a truce by introducing what he calls the Proportionality Principle, which allows for minor reclamation that enhances the value of the harbor and serves the public interest. "It is meant to be permissive," Chu wrote to Secretary for Justice Wong Yan-lun, which prompted the government to move forward with projects that had been on hold, including new harborfront promenades and a bridge between Kwun Tong and the redevelopment of Kai Tak.

Chu says the same principle should apply to reclamation outside the harbor. "We are not fundamentally opposed to the prospect, but do it only if you have adequate justification," he says. For the time being, he believes, that justification simply does not exist. "Hong Kong will eventually have 10 million people. You will need 3,000 to 5,000 hectares to house them. You could destroy the whole of the harbor and all the coastlines and still not achieve that figure."

Reclamation is certainly problematic. Because it involves dredging the seabed, increases water pollution by stirring up heavy metals, pesticide residue and other toxins that have been absorbed into the soil. It also destroys local marine habitats, like that of the endangered Chinese white dolphin. Many say it also damages one of Hong Kong's defining characteristics: the dramatic relationship between mountains and sea, which manifests itself in craggy shorelines and dozens of small bays and inlets.

Opponents to reclamation point to a viable alternative: developing more land in the New Territories, much of which is currently occupied by abandoned farms, junkyards and illegal structures. According to a study by the University of Hong Kong in 2000, there are around 12,000 hectares of undeveloped land in the New Territories, excluding country parks and the outlying islands. In particular, 3,000 hectares are available in Kam Tin, a large valley that is sparsely developed despite the opening in 2003 of the Kam Sheung Road MTR Station.

For development to shift to the New Territories, however, the government would need to reform the Small House Policy, which gives each male indigenous villagers the right to build a 2,100-square-foot house in his ancestral village. Critics have attacked the policy as one that will lead to suburban sprawl and inefficient land use, but changing it would likely ignite a political firestorm, given that the organization that represents indigenous villagers, the Heung Yee Kuk, maintains a seat on the government's Executive Council.

For the government, then, reclamation is simply the easiest option. "Over the past few years, we have been facing challenges both in the land resumption and urban renewal processes due to fragmented and absentee ownership, as well as disputes over compensation and re-housing arrangement," says a spokeswoman for the Development Bureau. Reclaimed land comes with none of the same strings as urban renewal or rural land development, with their vested property interests, political headaches and social welfare concerns.

Still, reclamation is a hard pill for the public to swallow, especially when past decades of aggressive development have left many communities with lingering resentment. When the government proposed reclaiming a section of Junk Bay shoreline for a new highway, Tseung Kwan O residents spent years fighting the scheme until the government finally relented and adopted an alternative plan that would maintain public access to the waterfront.

The government has long been accused of approaching such projects with a bull-headed attitude. In 1995, when Christine Loh, Winston Chu and others were first lobbying against harbor reclamation, the government steadfastly refused making any concessions to its plans. "When you know you're right, you have to stick to your guns," said the government's chief planner, Edward Pryor, at the time.

Community activists say that, even if compromises like the one made in Tseung Kwan O have become more common, an "arrogant" attitude still pervades the government's senior ranks. "For years, they didn't have to consult the public," says John Bowden, who helped Tseung Kwan O residents fight the proposed waterfront highway. "The civil service has started to listen, but the senior management is stuck in the colonial era. There is a complete lack of trust."

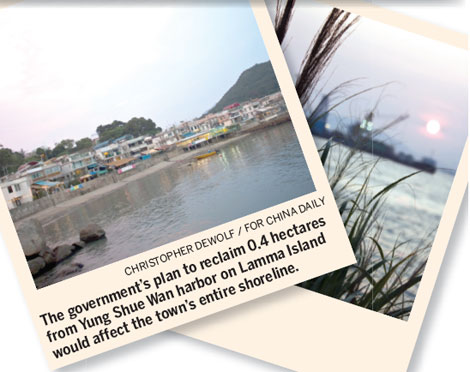

Already, some small reclamation projects outside the harbor have generated controversy. Ten years ago, the government reclaimed part of Yung Shue Wan harbor on Lamma Island to build an emergency helipad, sewage treatment plant and rubbish sorting facility. In 2003, it proposed reclaiming another 0.8 hectares of the harbor to build a 4.5-meter-wide emergency access road to the helipad, along with new space for residential and commercial development. The reclamation would have drastically altered the face of Yung Shue Wan, a small town of 6,000 inhabitants known for its family-run shops and seafood restaurants. Residents were so strongly opposed, the government quietly shelved the plan. Little was mentioned of it in the years after.

Then, last winter, to the surprise of many Lamma residents, the Civil Engineering and Drainage Department quietly introduced a scaled-back reclamation plan, publishing details only on its website and in the Standard, a free newspaper that is not distributed on Lamma. Seaside restaurant owners complained that they had not been notified of the new plan, even though it would require the removal of their waterfront dining areas.

"This is the government's approach - they just draw a line, pour the concrete and that's it," says Jo Wilson, the chairwoman of Living Lamma, a community concern group. When Wilson first moved to Lamma in 1995, the government was moving ahead with the first phase of the reclamation project. Local architects and urban planners proposed an alternative plan that would maintain the harbor's natural shoreline, but it was rejected outright. The reclaimed land is now used as a dumping ground for construction waste and rubbish. Highway-style guardrails and barbed-wire fences line the waterfront.

Lamma Island's district councillor, Yu Lai-fan, says her office has distributed more than a thousand questionnaires for local residents, and more than half of residents are in favor of the reclamation works. But no formal public consultation session is planned, according to the Development Bureau. "We have started dialogue with some of the locals and they generally support taking forward the project," says a spokeswoman for the bureau.

Wilson says the local efforts to engage the government have come to naught. "We have gone through all the right channels and nothing has come of it. It's very, very frustrating. Everything is put together by engineers and bureaucrats with no sensitivity to how it will affect the people who live here."

For John Bowden, Lamma Island is just a sign of what will come if the government pursues more reclamation projects. "The minute you antagonize a community, it will take years to bring them back on your side," he says. "People have realized that they can say 'No,' and they can stop whole projects. There will be a lot of objections until things are done right."

(HK Edition 10/11/2011 page4)