A house subdivided

Updated: 2011-09-01 06:31

By Ming Yeung(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Chin Kwai-lam sits in a factory-converted room. He lives with four other households. The families may be evicted in October as ordered by their landlord. Yik Yeung-Man / For China Daily |

|

After a long day of work, Chin Kwai-lam (left) and Liang Fawei share a cigarette break in Liang's 250-square-foot unit. Yik Yeung-Man / For China Daily |

|

Li Hung-ha lives in a 150-square-foot factory-converted room in Tai Kok Tsui which she says her 11-month-old baby cannot stand the poor hygiene and heat during extremely humid summer months. Yik Yeung-Man / For China Daily |

With rents and land prices shooting up, and the government cracking down on illegal, subdivided accommodations, many families still live in fear of becoming cast out onto the street with nowhere to turn. Ming Yeung reports.

It's cramped and musty in what Chin Kwai-lam and his family call "home". The dwelling on Bedford Road in Tai Kok Tsui used to be a garment factory. Now it's dilapidated and derelict.

The tiny abode is only 200 square feet. It's cluttered. Clothes and cooking utensils are scattered among Chin's other meager possessions. He barely has room to move.

It's all he can afford. There's nowhere else to go.

Hong Kong's property prices soared to a 13-year high in February. In lock step, landlords moved frantically to jack up rents. The increases were dramatic - with landlords raising rents 20-30 percent year on year.

There's no rent control and tenants in cramped, partitioned apartments in which several people reside, pay more per square foot of living space than people in luxury flats.

Chin says the family pays HK$2,500 a month and a few hundred Hong Kong dollars over and above that for water and electricity, accounting for one third of his wife's monthly salary. Chin does casual jobs and he cannot rely on his income from one month to the next.

Chin's his family lives there, more or less protected because they are in a legal gray area. Fire hazards are much greater in old factory buildings than in residential units. Moving into a residential building presents no option for Chin. He says the rent in a residential building would be double, or HK$5,000 a month, at least.

The family has been in the place for more than three years - awaiting allocation to public housing. The situation is not secure. The landlord demolished all subdivided flats on the upper two floors of the building. Only five families remain in the building.

The landlord issued a legal notice to Chin and his neighbors in May requesting that they move out by the end of June. They're still there. But rumors are floating around that everyone will be evicted in October. Chin now lives in terror that he and his family could end up on the street.

At dead end, Society for Community Organization (SoCo), a poverty advocacy group, suggested that the tenants not move from their illegal abodes unless they are relocated to public housing, transit centers or interim housing.

Transit centers and interim housing are temporary accommodations provided by the Housing Authority (HA) for those who become homeless as a result of natural disasters or clearance operations.

SoCo estimates subdivided flats in industrial buildings house more than 10,000 low-wage earners, the majority of whom are waiting for public housing.

The HA says it has plans to build 75,000 public housing units during the next five years, averaging about 15,000 new flats per annum.

But the supply is vastly inadequate, observes Sze Lai-shan, community organizer from SoCo, adding that grassroots families like Chin's are in a long queue waiting for public housing. By the end of March, about 152,400 applicants were on the waiting list. The average waiting time is three years.

At a meeting with a group of subdivided flat residents on Aug 23, lawmaker Leung Yiu-chung made a promise to Chin that he will discuss the matter with the HA and try to re-house the affected families to interim housing as soon as possible.

"Compulsory demolition (of illegal subdivided flats) perhaps is necessary for the sake of your safety, but it can only be done after your relocation is taken care of. How nerve-racking it is to live constantly under threat," Leung told the people at the meeting.

When local light industry migrated to the mainland in the early 1990s, an abundance of industrial buildings and warehouses were left vacant in older factory areas such as Tai Kok Tsui, San Po Kong and Kwun Tong.

Seeing the housing needs of the working poor, owners of vacant industrial buildings were more than happy to convert the abandoned spaces into rooms to make extra money, disregarding that they were violating the law.

The trend toward living in flats in converted factories began just a few years ago. The flats offer cheaper rent for relatively bigger floor space. The "easy-come-and-go" atmosphere attracted poverty-stricken people who can barely afford deposits required by residential building owners.

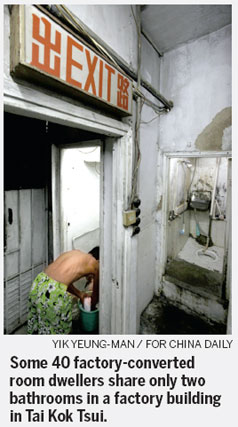

Li Hung-ha also lives in a room in a converted factory building. The single mother lives with her 11-month-old son in a factory on Larch Street. The floor has subdivided into 39 rooms, no more than 150-square-foot each. About 40 people share the space which has two washrooms and three shower rooms in one corner.

Li moved to the factory building in 2009 when her pregnancy forced her to stop working. Losing her job meant she could no longer afford the subdivided room in a private residence in Mong Kok.

Since the whole floor is partitioned entirely by wooden planks, cooking on gas stoves is strictly prohibited in Li's building, owing to the fire hazards.

"I fear nothing but a fire. If there's a fire, there's no way out," Li complains.

Apart from unauthorized door openings that do not meet fire safety requirements, common problems in such units are the addition of partitions that block fire escape routes and the overloading of buildings because of excessive partitions and raised floor platforms.

Li tells China Daily that people from the Buildings Department (BD) occasionally knock on the doors, wanting to come in to carry out inspections. The tenants just ignore them, she says.

The BD intended to break into the flats on Aug 22, but temporarily suspended the plan after negotiations with SoCo. The organization is lobbying legislators to relocate the affected tenants.

"Breaking into the building will not ultimately solve the problems. If the tenants are evicted, they will reside in another industrial building," Sze Lai-shan notes.

The BD did not respond to China Daily's inquiry about how the department handles situations when landlords refuse to comply with demolition orders as well as relocating displaced tenants, commenting that the department "has been occupied by other commitments recently".

Under the Buildings Ordinance, officers can break in to a premises for an inspection, in the presence of police, to find out if there are unauthorized additions or alterations that affect fire or structural safety of a building.

Li says she wants to find a safe and decent room because her baby suffers given the poor hygiene and the heat during the extremely humid summer months.

"The one more month CSSA (Comprehensive Social Security Assistance) payment released in July was mostly spent on my baby's medical treatment," she laments while looking at the toddler who has been unwell in the last few months.

Li and her baby rely on HK$6,000 social welfare a month. More than one third of it, HK$2,400, goes to rental. The remaining amount is barely enough to feed them, let alone provide sufficient funds to move.

Lawmaker Leung Yiu-chung is urging the Social Welfare Department (SWD) to help needy people pay deposits and other expenses if they are to be moved back to private residences.

A spokesman for the SWD replies that the department works with Integrated Family Service Centres to link up with people in need, especially elderly and disabled people, to whom they offer assistance.

The department will also take into consideration the circumstances of individual needs, the spokesman adds, to grant special emoluments to able-bodied people.

But according to Li, the SWD agrees to pay only HK$4,000 to subsidize her and she needs at least HK$8,000 in total for all expenses.

Chin Kwai-lam's neighbor Liang Fawei says he prefers to live in interim housing rather than a private residence not because of the skyrocketing rental rates but because of the limited space.

Liang's family will be allocated a room in public housing in 2012 at the earliest.

As advised by Liang's welfare officer, the family of five could consider applying for CSSA so that the household would get rent allowance as well.

According to SWD's mechanism, rent allowance granted to social welfare households ranges from HK$1,265 for a person to HK$3,545 for four people.

"It's not about the pecuniary assistance. Even if I can afford HK$6,000 for rental a month, there's no way I can find a room as good as this one," he stresses.

Now living in a 300-square-foot room, the family once rented a flat half that size on Canton Road for HK$4,100 a month.

Liang recalls the rooftop unit was boiling hot, forcing them to move back to the factory building.

"I have no other requests. I just wish that we will be granted a place in interim housing before October, before we are evicted and end up living on the street," Liang says, faintly.

|

Many industrial buildings have been left vacant in old factory districts like Tai Kok Tsui since the 1990s. Landlords thus partitioned the empty spaces into sub-divided flats which are now housing some 10,000 low-wage earners. Yik Yeung-man / For China Daily |

(HK Edition 09/01/2011 page4)