A room at the top

Updated: 2011-08-03 07:12

By Kane Wu(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

Housing accessibility remains one of the leading sore points in the city's social climate, as home prices exceed the means of most, and thousands upon thousands are forced to live in illegal structures. Kane Wu reports.

At the end of her 10-hour work day, Siu-hung doesn't even break a sweat during the climb up 10 floors to her home on the rooftop platform of a building in Sham Shui Po.

In that tiny, 400-square-foot apartment, built entirely of thick planks and paper board, she lives with her husband and two sons.

|

Siu-hung watches TV in her tiny living room. Kane Wu / China Daily |

"It's only HK$1,500 a month for rent. With electricity and water bills, it's some HK$2,000," says Siu-hung. She's a woman in her 40s, originally from Zhaoqing, Guangdong province, and she does not wish to reveal her full name.

Siu-hung came to Hong Kong in 2005 to be reunited with her husband. Her two sons were in primary school at the time. Siu-hung's husband had immigrated to the city earlier, in 2000, and has since become a permanent resident.

The family once lived in a regular 300-square-foot apartment, not far from their present location. The rent was HK$2,300 a month. As the two sons grew up, Siu-hung found the only bedroom seemingly became narrower and narrower.

"My elder son was big and fat. We four people could barely move in the bedroom," Siu-hung recalls. "I couldn't stand it anymore. One day a friend introduced me to the landlord of the rooftop apartment, and I didn't hesitate to sign the deal."

Siu-hung is one of the more than 100,000 people in Hong Kong living in cage homes, rooftop shanties or other forms of unauthorized building structures. Most are located in Yau Tsim Mong, Sham Shui Po and Kowloon City districts, says Chan Siu-ming, community organizer at the Society for Community Organization (SoCo).

Half of them live on social welfare, the other half are "working poor", Chan tells China Daily. "Most families in these districts earn less than HK$10,000 a month. They can barely survive if they have to spend HK$3,000 on housing," he says. "Thus, many of them choose to live in rooftop shanties, which are cheap and relatively spacious."

Siu-hung works at a construction site in Yau Ma Tei. She has a stable income. Her husband, however, is self-employed and in poor health. When both have jobs, the family makes some HK$15,000 a month. Since February this year, Siu-hung's husband worked for only three to four days a month. The rest of the time he was either visiting the doctor or staying at home. "We only make HK$9,000 a month now," Siu-hung says.

The rooftop shanty she lives in is divided into three bedrooms, with a double-deck bed in each. The top deck of the beds are covered with clothes, bags, and metal hardware, in a disorderly manner one would never expect to find in a normal home. There are only three pieces of furniture apart from the beds in the shanty house: a 50-cm-tall dinner table, a cupboard to place the television, and a computer desk in one of the rooms. All look dirty and battered.

"My two boys now can have one room of their own," she says happily, as the boys occupy themselves playing computer games in the next room. The elder will turn 18 in two months. The younger is a Form 2 student at a nearby secondary school.

|

Fung Ngan-oi stands outside her rooftop room made entirely of iron sheets. Kane Wu / China Daily |

"I give them HK$50 allowance every day. They can't afford anything else but meals and daily commute," Siu-hung says.

The rooftop shanty however is just a compromised shelter for Siu-hung and her family. Poor hygiene and the awareness of their insecure environment often bring her sharply awake in the middle of the night.

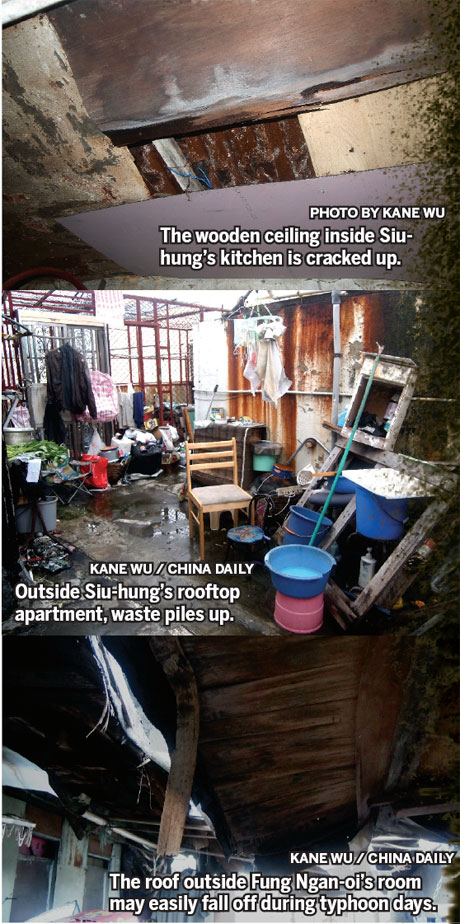

"It had been raining cats and dogs in the past few weeks. Can you imagine my entire apartment was almost submerged by the water?!" Siu-hung complains. "The rain fell inside the house from the holes on the ceiling. The wind almost blew the roof away!"

On hot sunny summer days, the shanty feels no better. "It's like a steam cage," Siu-hung says. "And I have to climb up 10 floors every day with my big sack! My knees feel weak and sore all the time. It is so easy to get ill in such a terrible environment."

What's worse, Siu-hung tells China Daily that drug dealers and addicts come to the rooftop frequently to do dope. "I'm really worried about my sons," she says. "Sometimes late at night I can still hear people talking. I don't know who they are. I can just lock the doors firmly."

Siu-hung says the police came up to her rooftop once to investigate a crime in the area. "Apart from that, nobody has ever warned us of any potential dangers. We have to be extra careful ourselves," she says. "I don't even know who lives next door on the same rooftop."

But she estimates there are about 10-12 households sharing the same rooftop, a place no bigger than 3,000-square-feet. These shanties are knitted tightly together. Residents seldom walk out to the common area, where clothes hang and daily waste piles up.

"There are many potential hazards on rooftop shanties, fire being the worst of all," Chan Siu-ming says. His organization pays regular visits to rooftop residents to see whether they need help.

"The rooftop residents were all appalled when they heard about the Ma Tau Wai fire in June. They were saying that if the same thing were to happen to them, they wouldn't even know where to run," says Chan. "The rooftop is such a small place with so many inflammable materials, there is no way out."

On June 15, an old, eight-story tenement building in Ma Tau Wai was severely damaged in a fire that caused the deaths of four people and injured at least 20.

That fire has once again raised alarms about potential hazards on unauthorized building works. The Buildings Department says illegal rooftop structures on the buildings whose highest floor is more than 13 meters above the ground level will obstruct the fire refuge area for residents, thus posing a serious fire safety risk.

Back in 2001, the department launched a special enforcement operation to remove illegal rooftop structures on some 5,500 single staircase buildings within seven years. Up to now, the department says it has completed operations on 5,370 buildings, ordering removal of more than 400,000 illegal structures, according to a document submitted to the Legislative Council.

Separately, a number of large-scale operations have been initiated since April this year to remove unauthorized building works on rooftops, in yards and lanes, in respect of some 500 target buildings each year, the department says.

However, Chan says these removal operations do not solve the problem fundamentally. "Why are so many people living on the rooftop? It's because they can't afford to live anywhere else. If you take down their houses, where should they go?"

Chan says 80 percent of rooftop dwellers are waiting for their application for public housing to be approved by the government. The processing period is usually three to four years.

According to Chan, 100,000 families filed applications for public housing in 2006. This year, the number has already exceeded 150,000. "But the government adds only 15,000 new public housing units every year," he says. "It keeps the current quota so that they can reserve more land for property developers, while poor people are left homeless."

Fung Ngan-oi, a mainland immigrant who lives with her son on a rooftop shanty in Yue Man Square, Kwun Tung, is just on the verge of becoming homeless. She married twice to men from Hong Kong. Her first marriage produced two children, a girl and a boy. Fung has been widowed twice. The siblings came to Hong Kong in 2001 and Fung reunited with them in 2008 in a 150-square-foot shanty built with iron sheets.

"The room is like a living inferno in the summer, because there is no air-conditioner," Fung complains. "I have to keep the door open when sleeping at night and my dog will bark if any stranger comes up." She also has to carry buckets of water from the fourth floor to the rooftop, because water tubes are broken in her bathroom.

Strangers often come up to the rooftop when Fung is at work, stealing items from the shabby shanty. "I keep all valuable things in my daughter's place. She moved out when she married a local guy," Fung says.

The government called her earlier this year, informing her that the rooftop, together with the building, will be reconstructed within two years. "They told me to move out but didn't give me a deadline or a housing option," says the 53-year-old cleaner, who lives on the HK$28/hour minimum wage. "We can barely make ends meet every month and I don't have any relatives here. If the government doesn't grant me public housing unit soon enough, I'll have to sleep in the streets!"

Fung pays HK$1,200 for her room on the rooftop. Her son pays his own share. Both filed applications for public housing a couple of years ago and are on the waiting list. "I really don't have a way out," she says. "So I'll wait. I'm not going anywhere until the government grants me a place to live."

"The reconstruction operations will work well only when there is a corresponding relocation policy," comments Chan Siu-ming from SoCo. "We demand that the government give priority to rooftop shanty dwellers when allocating public housing units."

Siu-hung also dreams of a public housing unit. Her husband, who acquired permanent residency in Hong Kong, applied for public housing 10 years ago. "Last year the Housing Department showed us a unit in Ho Man Tin. Somebody died in it before. Two weeks ago, it took us to another place, right beside a landfill site. It was smelly as hell. I declined both offers. Why can't the government give me a new apartment?" she complains. She will have to wait for at least another year before the government takes her to another public housing tour.

"Day and night, my one and only hope is that the government will allocate a brand new apartment in the public housing estates to our family as soon as possible," says Siu-hung, massaging her aching knees.

Night falls. Siu-hung's husband hurries to get dinner ready in the unlit kitchen. Looking up from the rooftop, she finds neon lights starting to shine over at Langham Place, a deluxe shopping mall and hotel not far away from where she lives. She sighs and walks inside to the dinner table. A mouse is dead on the stairs. It's starting to smell.

(HK Edition 08/03/2011 page4)