The thin line between fantasy and reality

Updated: 2011-07-30 09:08

By Elizabeth Kerr(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Angry and unhappy Walter Black finds the best way to deal with his world is through a hand puppet simply referred to as The Beaver. It is a singularly eerie and resonant performance by Gibson. |

Gibson's latest performance either a brilliant comeback or the nail in the coffin. Elizabeth Kerr reports.

Our relationship with our celebrities is a curious and precarious thing. We like to know things about them and thereby "know" them somehow. So much so that we've made stars of so-called normal people with reality television, and there's really no need to detail the impact of the 24-hour Twitter age. But we feel we have a right. They are literally nothing without us. There was a time that shocking secrets about the celebrity of the day only came to light after he or she died. The concept of "private" no longer exists, either personally, by choice of behaviors, or professionally, by choice of the media-saturated public and its proxy actors.

So we know Tom Cruise is a self-righteous cult member - or a devoted Scientologist depending on your point of view - on the receiving end of a backlash, so his cameo as a reprehensible studio executive in Tropic Thunder was nicely tongue in cheek. We know, say, Oprah Winfrey, is the product of an abusive childhood, making her Horatio Alger rise to the top of the Fortune 500 all the more inspiring. And we know more about Edison Chen's libido than we really want to (an egregious case of Too Much Information if ever there was one) and the reception he receives for his next romantic lead will be, er, interesting. The point is all that heretofore confidential information in the Tell All age is that anything any of these people do now, in the absence of a public/private disconnect, is shaded, and very often shaped, by that knowledge.

So when your favorite movie star gets busted on a drug charge, you watch their new film about alcoholism through a fresh filter. Is it fair? Perhaps not, but it happens nonetheless. Action star Jean-Claude Van Damme's myriad romantic, financial and legal woes were fodder for the ultra-meta JCVD, a film that blurred the line between real life and performance so brilliantly it deserved its own special Oscar. Similarly, watching Mel Gibson as a seriously mentally disturbed middle-aged husband on a downward spiral so odd and fueled by such anger it destroys his marriage and his career, well It's a little creepy.

The Beaver has been floating around since early 2010, ready for release and promotion just as its star, Gibson, made headlines for the vitriolic messages he spewed at his former girlfriend - which included death threats and as many pejoratives for "woman" as exist. This after his anti-Semitic rant to a cop when he got caught driving drunk about a year earlier. Is it possible to watch Gibson as simply an actor any more and judge him on his performance alone?

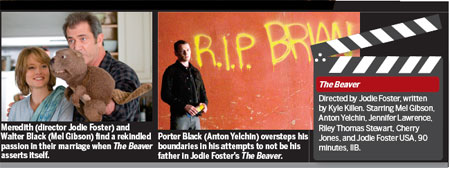

In The Beaver, Gibson is Walter Black, a toy magnate suffering crippling depression that is either a symptom or the cause of his middle-aged, upper middle-class malaise. He has a workaholic wife, Meredith (director Jodie Foster), and two sons he neglects enough to justify a call to Child Protective Services. His youngest Henry (Riley Thomas Stewart) is being bullied and his eldest, Porter (Anton Yelchin), is itemizing the ways he's like Walter and actively trying to avoid them. After Meredith stops enabling him, Walter attempts suicide, fails, and discovers an alter ego that helps him reconnect with the world. It's a discarded beaver hand puppet that sounds curiously like Ray Winstone.

The Beaver is Gibson's film. His worn, embattled visage is the perfect portal into both Walter and Gibson's turbulent psyche. Whatever your feelings on Gibson version 2.0, he's shown a knack throughout his career to immerse himself in a given role and end up creating a nearly iconic character, Mad Max and Martin Riggs being the best and best known of the lot. In The Beaver he gives a totally committed performance, and proves he hasn't lost his knack for making the ridiculous seem earth-shatteringly vital. Add to that the veneer of true-life tragedy (if your definition of tragedy includes misogyny and anti-Semitism) and the film becomes a must-see for ambulance chasers and an experiment in art imitating life - or vice versa.

There are a number of threads running along beside Walter's in The Beaver that Foster and writer Kyle Killen never quite get a handle on. Is this a talking animal as a way of dealing with psychosis movie la Harvey or the new FX series Wilfred? Is it an American Beauty-style Suffering Affluent White Folks drama? Is it satire (and when you see the scene where The Beaver and Walter erupt in fisticuffs you'll understand where that question comes from)? It's hard to tell; the script flits from one element to the next, never touching down long enough to make anything matter. Ultimately the movie is about buried rage and grief, but Porter's daddy issues just aren't that gripping a sub-plot. The parallel drawn between Porter and Walter is about as subtle as a mallet: Porter speaks by writing academic papers for other students to fund his great escape from his family, just like Walter speaks through The Beaver. Yes, that's a mallet.

Despite reasonably strong performances by Yelchin (Star Trek) and Jennifer Lawrence (Winter's Bone, X-Men: First Class) as his high school crush Norah, the film isn't served by the wispy, watery romance between the two. Somehow they encourage each other to emotional maturity but the hackneyed handling of their relationship, again, only goes halfway. And it's difficult to care about Porter when, in a turn that only happens in the movies, he mopes around - depressed - when he has to face the consequences of writing said papers. In the way comedy characters always forgive obnoxiousness in friends the way no one would in reality, Porter is shocked by his punishment. By the time the requisite hugging and tearful family reaffirmations and understanding roll around, the far more compelling elements Gibson's performance flirted with are forgotten.

So the question becomes one of how much audiences are willing to separate the man from the actor. This is Foster's first directorial effort in over 15 years (the last was Home for the Holidays) and it shows. She quite publicly came to Gibson's defense in the wake of his PR difficulties, logical based on the fact Gibson, ironically, is the best reason to see The Beaver.

The Beaver opened in Hong Kong on Thursday.

(HK Edition 07/30/2011 page4)