Many bridges to cross

Updated: 2011-07-06 07:19

By Christopher DeWolf(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

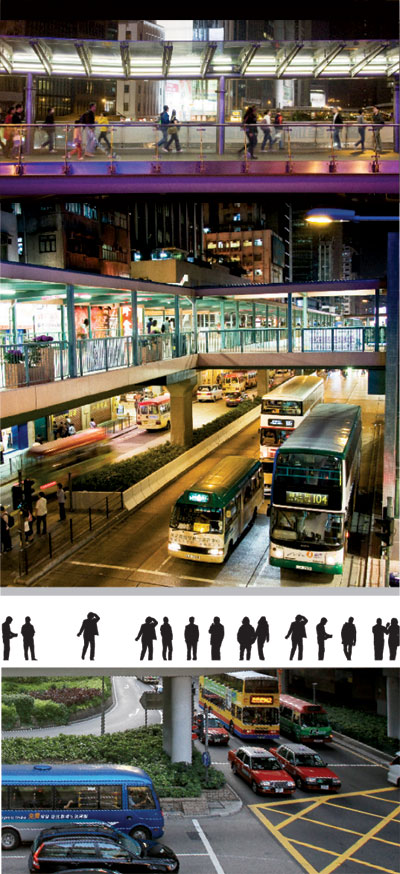

Hong Kong may claim status as one of the world's most distinctively three-dimensional, vertical cities. The city's vibrant, high-level urban pedestrian network is connected by the many footbridges that link those famous high-rises, so that one may enjoy sheltered walks extending over kilometers without ever touching street level. Christopher DeWolf reports.

It's a bright Sunday afternoon and Central is buzzing. Thousands of Filipino domestic workers gather with friends for a weekly picnic. Shoppers stream through the luxury shops of Chater House to the somewhat less posh confines of Worldwide House, where large boxes of gifts are being packed for shipment to the Philippines. Charity workers stop passersby to ask for donations.

Hong Kong is famous for this kind of vigorous street life - except in this case, none of it is happening on the street, but instead one or two stories above ground, on the network of footbridges and elevated open areas that link many of Central's shopping malls and office towers.

It isn't just happening in Central. In dozens of spots around the city, from Tsuen Wan to Tseung Kwan O, footbridges and underpasses create pedestrian networks that extend well beyond the traditional domain of the sidewalk and public square. In the words of one architect, Hong Kong has entered into a "condition of groundlessness," in which the ground has become just one of many layers of public activity.

The phenomenon has become so pervasive that, in many parts of Hong Kong, vast networks of interconnected malls, office towers and residential buildings have become the main form of pedestrian passage. It is possible to walk from Pacific Place Three, on the western edge of Wan Chai, all the way to the Hong Kong-Macau Ferry Terminal in Sheung Wan - a distance of more than two kilometers - without once setting foot at street level.

"Hong Kong is a vertical, three-dimensional city, while other cities are essentially two-dimensional," says Jonathan Solomon, acting head of the University of Hong Kong's School of Architecture. Public activity in most places takes place in two spheres: public outdoor space and private indoor space. But in Hong Kong, says Solomon, "ownership is less significant than use", and the lines between public and private space have blurred to the extent that a pedestrian walking through the city will constantly pass through public and private space without taking note of the difference.

"Footbridges enabled that to happen, because they change the nature of space," says Solomon. "In Hong Kong, it's an economic necessity for buildings to be connected at multiple levels above and below ground."

This fall, Solomon and two other architects, Clara Wong and Adam Frampton, will publish Cities Without Ground, a "guide to the vertical city" that maps 35 different three-dimensional urban networks around Hong Kong - most of them are built around MTR stations and shopping malls.

Similar networks exist in other cities - most buildings in the center of the Canadian city of Calgary for example, are connected by 16 kilometers of footbridges and elevated passages, including a covered public park located inside a shopping mall. But they are nowhere near as widespread as in Hong Kong.

Part of the reason for that is geography. Much of Hong Kong is built on steep slopes, with sometimes dramatic drops in elevation from one block to the next. Wan Chai's Hopewell Centre, for instance, has two ground-floor entrances: one on Queen's Road, at sea level, and another on Kennedy Road, 17 floors above.

As Hong Kong boomed in the postwar era, the lack of flat land in central areas encouraged extreme density. The most remarkable example of this was the Kowloon Walled City, a high-rise squatter settlement of interconnected buildings through which residents could pass without touching the ground. Each building was sprinkled with shops, restaurants and factories. Schools were opened on the rooftop, where children had a place to play outdoors.

Though this kind of multi-tiered activity took place throughout Hong Kong, the footbridge network was actually born in Central in the 1970s, when government engineer Benedict Kwong used them to link high-priced offices and shopping arcades like the Prince's Building, with newly-reclaimed land along the waterfront. When the MTR opened in 1979, footbridges became a popular tool to connect stations to surrounding housing estates and shopping malls.

The number of above- and below-ground crossings continues to increase. 179 footbridges and 89 pedestrian subways have been built by the government over the past 10 years - numbers that do not include the many footbridges built by private developers. The government is now studying the expansion of existing footbridge networks, such as the one running along Mong Kok Road, which could soon be extended west from Nathan Road to Tong Mi Road. A huge subway network has also been proposed for Causeway Bay, which would run from Victoria Park to the Happy Valley Racecourse.

In areas like Central, the footbridge network is seen as a great success, both in terms of facilitating pedestrian movement and expanding the amount of retail space. "There's little distinction between being on the ground and being on the footbridges," says Solomon. "They're both full of life, full of people - and full of shops."

But what happens when the ground is lost? While crowds bustle both on the streets of Central and above, in areas like Tseung Kwan O and West Kowloon, footbridges have been used as a way to clear streets of pedestrians. In several cases, footbridges and subways have replaced existing surface-level pedestrian crossings in order to increase the vehicular capacity of roadways. Last year, residents of Yuen Long complained about the lack of a ground-level crossing between a housing estate and a light rail station; local residents so disliked a nearby footbridge that many of them chose to jump a fence and jaywalk instead.

"You have situations like this, where people are moved to points where they don't necessarily want to go," says urban designer John Batten. "The overpasses and underpasses exist only to benefit car drivers, not pedestrians."

Batten points to the recent case of Salisbury Road in Tsim Sha Tsui. While pedestrians could once cross the street at ground level to reach Victoria Harbour and the Cultural Centre, a government project to improve traffic flow has now closed all surface-level crossings, forcing pedestrians instead, to pass through tunnels or underground shopping malls.

In June, a survey of 657 Tsim Sha Tsui pedestrians conducted by urban design watchdog Designing Hong Kong revealed that 77 percent, prefer using street-level crossings over footbridges and subways. But the same survey showed that, in rainy weather, just 19 percent prefer surface crossings, suggesting that what pedestrians want most is a multiplicity of walking routes. Seventy-two percent of survey respondents said they preferred taking the shortest route between two places.

"The problem is that bridges and tunnels force you into particular routes that limit your ability to take the shortest path," says Designing Hong Kong convenor Paul Zimmerman. "People also pick attractive routes. That's a very qualitative statement, but part of what makes a route attractive is being able to see other people, to window shop, to have an experience. With subways and footbridges that becomes quite limited."

Pedestrian comfort and convenience are just two factors on a list of eight criteria used by the Transport Department to evaluate the need for a footbridge at a particular locale. Others include traffic speed, road volume and accident rates, according to a spokeswoman for the department. Critics say that one factor - connectivity - should be given special consideration. If the footbridge provides more opportunities for a pedestrian to get from one point to another, it creates the opportunity for a complex, dynamic urban environment.

"One of the keys to avoid making the street level dead is to provide convenient inter-level connections," says architect Rocco Yim, who has designed many of Hong Kong's landmark buildings, including the new Tamar government headquarters in Admiralty and the International Finance Centre (IFC), an office, hotel and retail complex that opened in 2003.

IFC is built on a large podium above street level. It has been criticized for its lack of ground-level amenities. "That was because the planners insisted on putting facilities that are not activity-generating on the ground, like transport interchanges and (electrical) transformer bays," says Yim.

Above ground, however, IFC has become one of Central's focal points, thanks in large part to dozens of different connections to the surrounding area. Just about anyone walking from Central to the outlying island ferry piers passes through IFC, and many of its outdoor public areas, including the large rooftop garden, are gathering spots for office workers, teenagers and domestic helpers.

"I envisioned IFC as part of the city's fabric, even the indoors and more controlled environment," says Yim. "This is our new public realm. Instead of just streets and plazas, we also have this indoor network connected by lifts, escalators and bridges."

Jonathan Solomon sees it as a significant expansion of the city's public space. "That space in IFC in front of the CitySuper (supermarket), next to the footbridge going out to the ferry piers - that is a crossroads for so many different types of people," he says. "What urbanity requires is heterogeneity and the opportunity for chance encounters. You have that there."

Solomon even counts a footbridge among his favorite places in the city. "When we have some time on the weekend, I like to take my son to the footbridge that goes to the Star Ferry," overlooking the land being reclaimed to build an underground highway and surface-level park along the Central waterfront. "We stand there and watch the construction. It's one of the most interesting places in Hong Kong."

(HK Edition 07/06/2011 page4)