The art of giving

Updated: 2011-06-09 06:56

By Steven Chen(HK Edition)

|

|||||||

|

Participants in Sowers Action Walk for Education stop to greet children during the event. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Hong Kong charitable organizations play a big part in training mainland charities, as NGOs take on an ever-increasing role in filling the mainland's social safety net. Steven Chen reports.

March 2010: Some 200 people take to the pavements along the dusty streets of Gansu province, intent to undertake a 7-day ordeal to help rebuild educational facilities shattered by the 2008 earthquake that devastated Sichuan and neighboring provinces.

Participants will trek over 60 kilometers amid snow and chilly winds in the hope of raising charitable donations to help their cause. Among the hardy but happy contingent stood an animated group of organizers, speaking the unmistakable, distinctive dialect of Hong Kong Cantonese.

The 7-day odyssey is one of hundreds of programs being staged each year from Shenzhen to Guangzhou, to Yunnan and beyond.

With China's social welfare sector undergoing unprecedented expansion, more services are placed under management of NGOs. Hong Kong charities are taking a key role, stepping in to provide valuable assistance to the huge number of mainland charities and other NGOs springing up to fill the gaps in social services.

"We look at where we can help," says Margaret Chan, project officer for Sowers Action, one of Hong Kong's longest-serving charity organizations focusing on mainland projects.

|

Participants in Sowers Action Walk for Education in Gansu province. |

"Hong Kong charities provide much needed support, in training and management, and through fund-raising," says the fluent Putonghua-speaker, whose organization holds at least six events on the mainland each year. Each of the events aims to raise HK$2 million or more to provide for the education of children in the nation's neediest provinces.

Expertise in fund-raising, training and management is being provided to meet a rising demand, as the so-called third sector takes on a greater share of welfare work from traditional public sector departments. It's a sea change that began only a few years ago, say Hong Kong charity workers active across the border.

"This is especially true in Shenzhen," says Cheung Yuk-ching, a project coordinator for ISS HK, which works in partnership with a sister charity organization in the city that helps elderly residents, children and families in financial and relationship distress.

"We expect we will need around 5,000 social workers and volunteers over the next few years. Now there are just over 1,000. The local government has set a target like this so there is a lot of work to do.

"The idea of social work is a new concept on the mainland. Before there wasn't even such a field and the sector was so small. But now we are seeing more and more NGOs starting up and they will need quality staff to provide quality services."

It is in these areas - of developing quality staff and qualify services - that Hong Kong charities have expertise and can really make a difference.

"One of the biggest areas where we can help is in training," says Cheung, "Especially in the core areas of care work, group work and community work."

To date, "staff care of clients is more like a teacher to a student. Patients are 'instructed' on how to behave. Social workers here see this as an effective way to manage them. But we teach them how to get clients to open up and express themselves and talk about their needs."

|

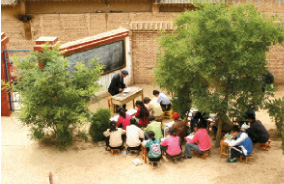

Students study in an outdoor class. Charity groups in Hong Kong are working with their mainland counterparts to provide support for students like these. |

Group work is another area that needs to improve, she says. In an environment where social stigma attaches to people in need, those who need help can be discouraged people from reaching out to others

"Clients are treated on an individual basis. We teach staff how to gather people with similar backgrounds and needs and encourage them to share their experiences with each other. This kind of group care gives clients some relief and a chance to bond with others, which helps create a more supportive environment."

The same holds true for the mentally handicapped, says Sam Yu, an assistant professor specializing in comparative social policy in the Department of Social Work at Baptist University.

He notes that during his many years of working alongside welfare agencies in Shenzhen and Guangzhou, "the approach is to treat clients as though they have a sickness that can be cured. It's a very 'medical' approach", he says.

"This creates problems because people may not get all the care they need. There is an expectation that if they are given enough care they will somehow 'get better'.

"Instead, we show how it's important to work with the (mentally handicapped) person, get them to express themselves and express their needs. We also encourage staff to work with parents and others in the surrounding environment. In Hong Kong, parents are very much involved in the operation of care centers. This is a new concept on the mainland."

The changes, Yu believes, create a more supportive environment for clients and will lower expectations of parents and welfare staff about what is possible.

"We're trying to change the perception of what is meant by the successful treatment and care of a patient."

A third area under critical review is community work, says Cheung.

"We want to train welfare staff and volunteers to be more positive in reaching out to the community. We teach them how to organize activities to get the whole community involved - for fund-raising, to give clients a relaxing activity or to just get them out in the community.

"There is some embarrassment about being poor or elderly. By getting them involved in community life, others can get to know these disadvantaged groups which fosters social harmony. The mainland is developing so rapidly economically. It needs to have a harmonious environment so it can cope with the stresses of these changes."

Another key area for change is in management of welfare groups, say the welfare experts.

Cheung's local partner Shenzhen Humanistics Social Service, Chan's Sowers Action and small charities like Ray of Hope Charity Foundation have introduced the concept of corporate governance to their mainland counterparts to improve transparency of operations and define standards of management and services.

"Hong Kong charities provide a lot of ideas," says Grace Liu, a vice-director of news services with China Charity Federation. The federation is one of the two largest NGOs operating on the mainland. Along with the Red Cross Society of China, it receives a substantial share of the charitable donations that make their way into welfare services.

What impresses Liu most is Hong Kong's range of charities and their specialization, she says.

"There are so many large and small charities in Hong Kong that are involved in different areas and provide many services.

"We don't have as many charities doing different things and the services they provide can be similar. This is something we can learn.

"Hong Kong charities also have a clear training system for staff and a good standard of service and management of volunteers. On the mainland, we are trying to improve ourselves. But social work is new, so we are not there yet."

Another area ripe for improvement is fund-raising, says Liu.

"We have fund-raising activities and last year did raise a lot, mainly from private donations and from companies. But we can do more. Hong Kong charities organize many events and often."

Indeed. It may be impossible to put a number on the fund-raising events organized on the mainland by Hong Kong charities each year. Sowers Action is a clear indication that the Hong Kong charities aren't afraid to think big. Its fund-raising efforts set multimillion-dollar targets. Its 10-month Long March of Education walkathon raised over HK$30 million, enough to build 140 new schools.

One area that appears to impede more rapid development of fund-raising by mainland charities is the lack of tax deductibility for donors. There's also a requirement that all donations be handled by trust funds which entail administrative fees.

"Donors like to see 100 percent of their money going to the charity," argues Cheung. "In Hong Kong, donations are tax-deductible. If a (mainland) donor sees that some of his donation is being used for administration he may not be happy."

However, the kind of corporate transparency, in the form of detailed reporting, detailed breakdown of services provided and a set of services standards, being introduced by Hong Kong charities may go a long way toward relieving donor fears about how the money is used.

While this form of corporate responsibility has yet to take off in a big way, there are signs that things are changing. Chen Guangbiao, one of the mainland's biggest philanthropists who regularly donates millions of yuan, and entertainment star Jet Li, who founded One Foundation, join a long list of benefactors from Hong Kong who have made charitable giving a high-profile activity. It may not be long before the wider business community sees donating as good business and a means to improve corporate image and get greater brand exposure.

"Hong Kong has a long history of charity organizations," says Yang Qinhuan, a social worker at China Charity Federation's Shenzhen office.

"There have been a lot of 'rescue' activities being carried out and supervision and training of frontline staff here. The field of social work is just starting to get solid. Hong Kong charities are helping us and helping improve our work."

|

New schools like this one are built with proceeds from many charity events organized by Hong Kong charities each year. |

(HK Edition 06/09/2011 page4)